Transcription

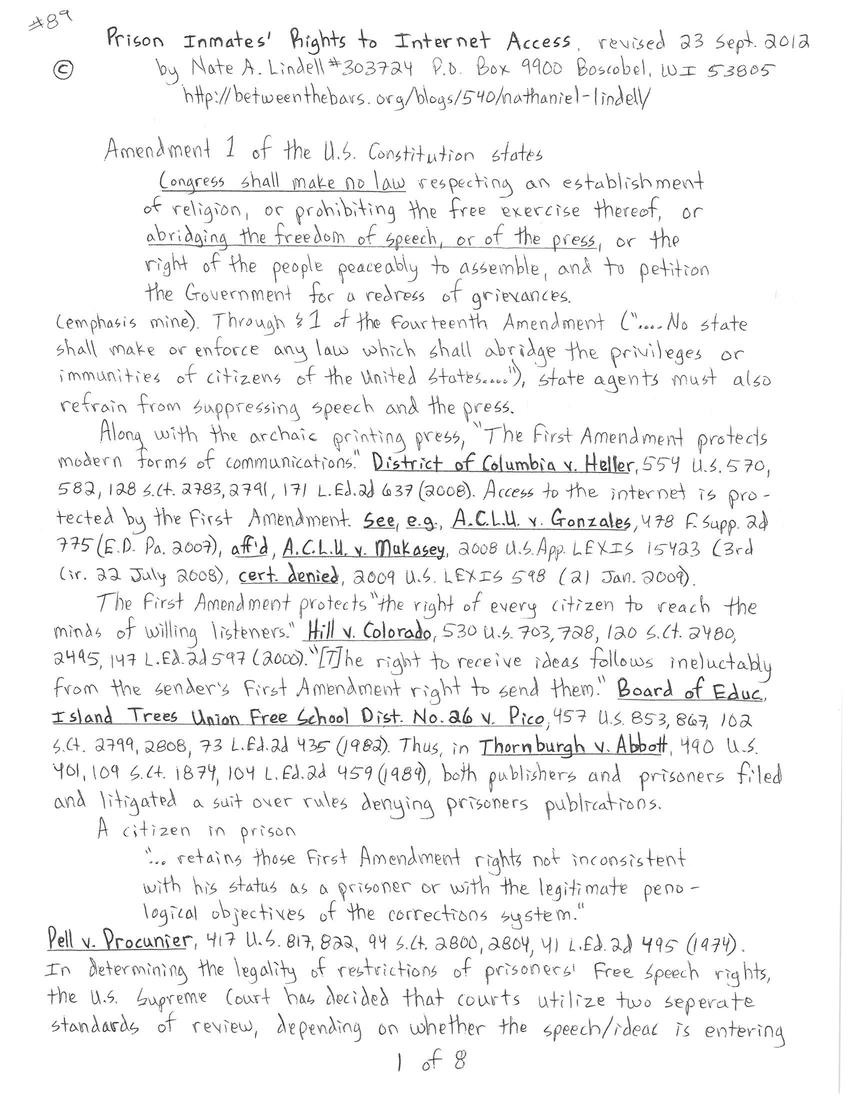

#89

Prison Inmates' Rights to Internet Access, revised 23 Sept. 2012

by Nate A. Lindell #303724 P.O. Box 9900 Boscobel, WI 53805

http://betweenthebars.org/blogs/540/nathaniel-lindell/

Amendment 1 of the U.S. Constitution states: CONGRESS SHALL MAKE NO LAW respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or ABRIDGING THE FREEDOM OF SPEECH, OR OF THE PRESS, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. (emphasis mine). Through Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment ("...No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States..."), state agents must also refrain from suppressing speech and the press.

Along with the archaic printing press, "The First Amendment protects modern forms of communications." District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 582, 128 S. CT. 2783, 2791, 171 L. Ed. 2d 637 (2008). Access to the internet is protected by the First Amendment. See, e.g., ACLU v. Gonzales, 478 F. Supp. 2d 775 (E.D. PA. 2007), aff'd, ACLU v. Makasey, 2008 U.S. App. LEXIS 15423 (3rd Cir. 22 July 2008), cert. denied, 2009 U.S. LEXIS 598 (21 Jan. 2009).

The First Amendment protects "the right of every citizen to reach the minds of willing listeners." Hill v. Colorado, 530 U.S. 703, 728, 120 S. CT. 2480, 2495, 147 L. Ed. 2d 597 (2000). "[T]he right to receive ideas follows ineluctably from the sender's First Amendment right to send them." Board of Educ. Island Trees Union Free School Dist. No. 26 v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853, 867, 102 S. CT. 2799, 2808, 73 L. Ed. 2d 435 (1982). Thus, in Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 U.S. 401, 109 S. CT. 1874, 104 L. Ed. 2d 459 (1989), both publishers and prisoners filed and litigated a suit over rules denying prisoners publications.

A citizen in prison "retains those First Amendment rights not inconsistent with his status as a prisoner or with the legitimate penological objectives of the corrections system." Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817, 822, 94 S. CT. 2800, 2804, 41 L. Ed. 2d 495 (1974). In determining the legality of restrictions of prisoners' free speech rights, the U.S. Supreme Court has decided that courts utilize two separate standards of review, depending on whether the speech/ideas is entering or exiting prison(s).

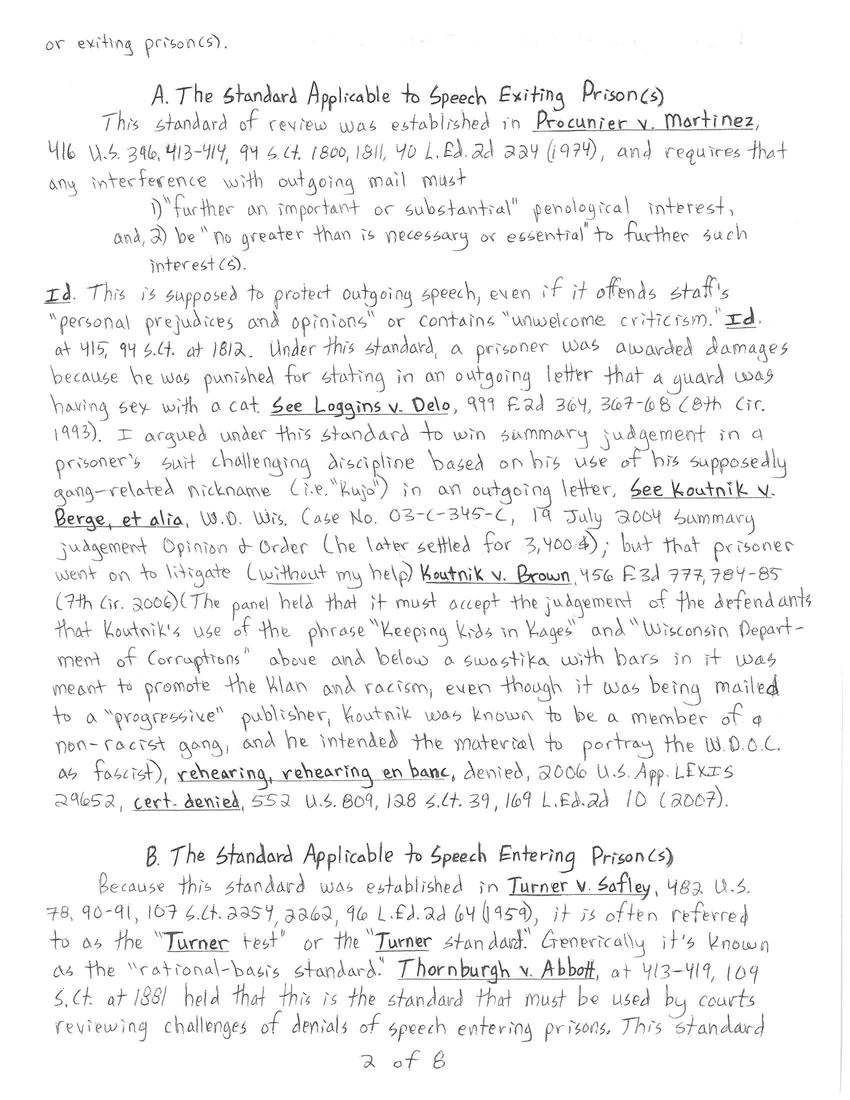

A. The Standard Applicable to Speech Exiting Prison(s)

This standard of review was established in Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396, 413-414, 94 S. Ct. 1800, 1811, 40 L. Ed. 2d 224 (1974), and requires that any interference with outgoing mail must 1) "further an important or substantial" penological interest, and, 2) be "no greater than is necessary or essential" to further such interest(s). Id. This is supposed to protect outgoing speech, even if it offends staff's "personal prejudices and opinions" or contains "unwelcome criticism". Id. at 415, 94 S. Ct. at 1812. Under this standard, a prisoner was awarded damages because he was punished for stating in an outgoing letter that a guard was having sex with a cat. See Loggins v. Delo, 999 F.2d 364, 367-68 (8th Cir. 1993). I argued under this standard to win summary judgement in a prisoner's suit challenging discipline based on his use of his supposedly gang-related nickname (i.e. "Kujo") in an outgoing letter. See Koutnik v. Berge, et alia, W.D. Wis. Case No. 03-C-345-C, 19 July 2004 summary judgement opinion + order (he later settled for 3,400$); but that prisoner went on to litigate (WITHOUT my help) Koutnik v. Brown, 456 F.3d 777, 784-85 (7th Cir. 2006). (The panel held that it must accept the judgement of the defendants that Koutnik's use of the phrase "Keeping Kids in Kages" and "Wisconsin Department of Corruptions" above and below a swastika with bars in it was meant to promote the Klan and racism, even though it was being mailed to a "progressive" publisher, Koutnik was known to be a member of a non-racist gang, and he intended the material to portray the W.D.O.C. as fascist), rehearing, rehearing en banc, denied, 2006 U.S. App. LEXIS 29652, cert. denied, 552 U.S. 809, 128 S. Ct. 39, 169, L. Ed. 2d 10 (2007).

B. The Standard Applicable to Speech Entering Prison(s)

Because this standard was established in Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 90-91, 107 S. Ct. 2254, 2262, 96 L. Ed. 2d 64 (1959), it is often referred to as the "Turner test" or the "Turner standard". Generically it's known as the "rational-basis standard". Thornburgh v. Abbott, at 413-419, 109 S. Ct. at 1881 held that this is the standard that must be used by courts reviewing challenges of denials of speech entering prisons. This standard permits prison staff to restrict incoming ideas if they claim AND YOU FAIL TO DISPROVE that the challenged rule or action was/is related to legitimate penological need(s). Id.

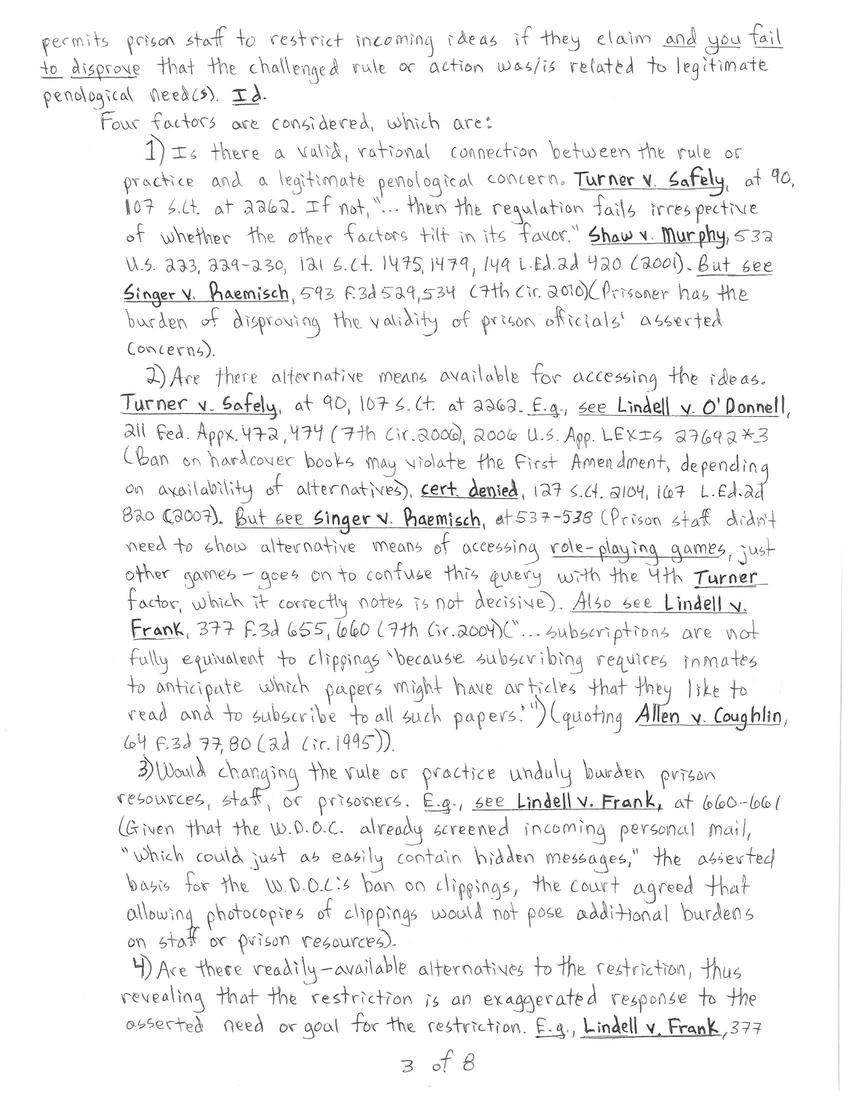

Four factors are considered, which are:

1) Is there a valid, rational connection between the rule or practice and a legitimate penological concern. Turner v. Safely, at 90, 107 S. Ct. at 2262. If not, "...then the regulation fails irrespective of whether the other factors tilt in its favor." Shaw v. Murphy, 532 U.S. 223, 229-230, 121 S. Ct. 1475, 1479, 149 L. Ed. 2d 420 (2001). BUT SEE Singer v. Raemisch, 593 F.3d 529, 534 (7th Cir. 2010) (Prisoner has the burden of disproving the validity of prison officials' asserted concerns).

2) Are there alternative means available for accessing the ideas. Turner v. Safely, at 90, 107 S. Ct. at 2262. E.G. see Lindell v. O'Donnell, 211 Fed. Appx. 472, 474 (7th Cir. 2006), 2006 U.S. App. LEXIS 27692*3 (Ban on hardcover books may violate the First Amendment, depending on availability of alternatives), cert. denied, 127 S. Ct. 2104, 167 L. Ed. 2d 820 (2007). BUT SEE Singer v. Raemisch, at 537-538 (Prison staff didn't need to show alternative means of accessing ROLE-PLAYING GAMES, just other games - goes on to confuse this query with the 4th Turner factor, which it correctly notes is not decisive). ALSO SEE Lindell v. Frank, 377 F.3d 655 (7th Cir. 2004) ("...subscriptions are not fully equivalent to clippings 'because subscribing requires inmates to anticipate which papers might have articles that they like to read and to subscribe to all such papers'.") (quoting Allen v. Coughlin, 64 F.3d 77, 80 (2d Cir. 1995)).

3) Would changing the rule or practice unduly burden prison resources, staff, or prisoners. E.G., see Lindell v. Frank, at 660-661 (Given that the W.D.O.C. already screened incoming prison mail, "which could just as easily contain hidden messages", the asserted basis for the W.D.O.C.'s ban on clippings, the court agreed that allowing photocopies of clippings would not pose additional burdens on staff or prison resources).

4) Are there readily-available alternatives to the restriction, thus revealing that the restriction is an exaggerated response to the asserted need or goal for the restriction. E.G., Lindell v. Frank, 377 F.3d at 660-661 (Given that the W.D.O.C. allows prisoners to receive other mail that could (more!) easily have codes in it, the ban on receiving clippings out of fear they'd have codes was an exaggerated response to such a fear and thus failed the Turner scrutiny). BUT SEE Singer v. Raemisch, 593 F.3d at 539-540 (The 4th Turner query is not necessarily decisive).

It's CRITICAL that you be prepared - gather evidence, review all possible reasons for the restriction(s), and do good discovery requests! - to address each of these four factors and demonstrate how they weigh in YOUR favor at the summary-judgement stage of the litigation.

In Jackson v. Pollard, 208 Fed. Appx. 457, 459 (7th Cir. 2006), one W.D.O.C. prisoner succeeded in arguing down the rationale for a W.D.O.C. policy that denied him e-mails printed from a pen-pal website and mailed to him in response to his ad, because he was already allowed letters in response to his ad. But, in Rogers v. Morris, 34 Fed. Appx. 481, 482 (7th Cir. 21 Mar. 2002), 2002 U.S. App. LEXIS 4866, the court dismissed a prisoner's challenge to the same policy, explaining that he'd failed to demonstrate its irrationality. A challenge to the W.D.O.C.'s ban on placing ads in newspapers and on pen-pal websites paid for by funds in a prisoner's trust account was likewise dismissed due to the prisoner inadequately explaining it. See George v. Smith, 507 F.3d 605, 609 (7th Cir. 2007) (Ads concerning political candidates or policy change would be protected, but not ads seeking help escaping, and "lonely-heart" ads also doubtful). And, most recently and most lamentably, in Woods v. Comm'r of the Ind. Dept. of Corr., 652 F.3d 745, 751 (7th Cir. 2011), my circuit concluded:

Here, the I.D.O.C. reasonably perceived that continuing to allow inmates to use [pen-pal] sites would passively enable fraud. The regulation enacted [prohibition, upon threat of punishment, of prisoners being listed on pen-pal sites] squarely addresses the threat and is therefore constitutional.

- This ruling paves the way for the W.D.O.C. and Illinois prison system, which both are included in the 7th Circuit's jurisdiction, to also enact a ban on prisoners posting internet pen-pal ads.

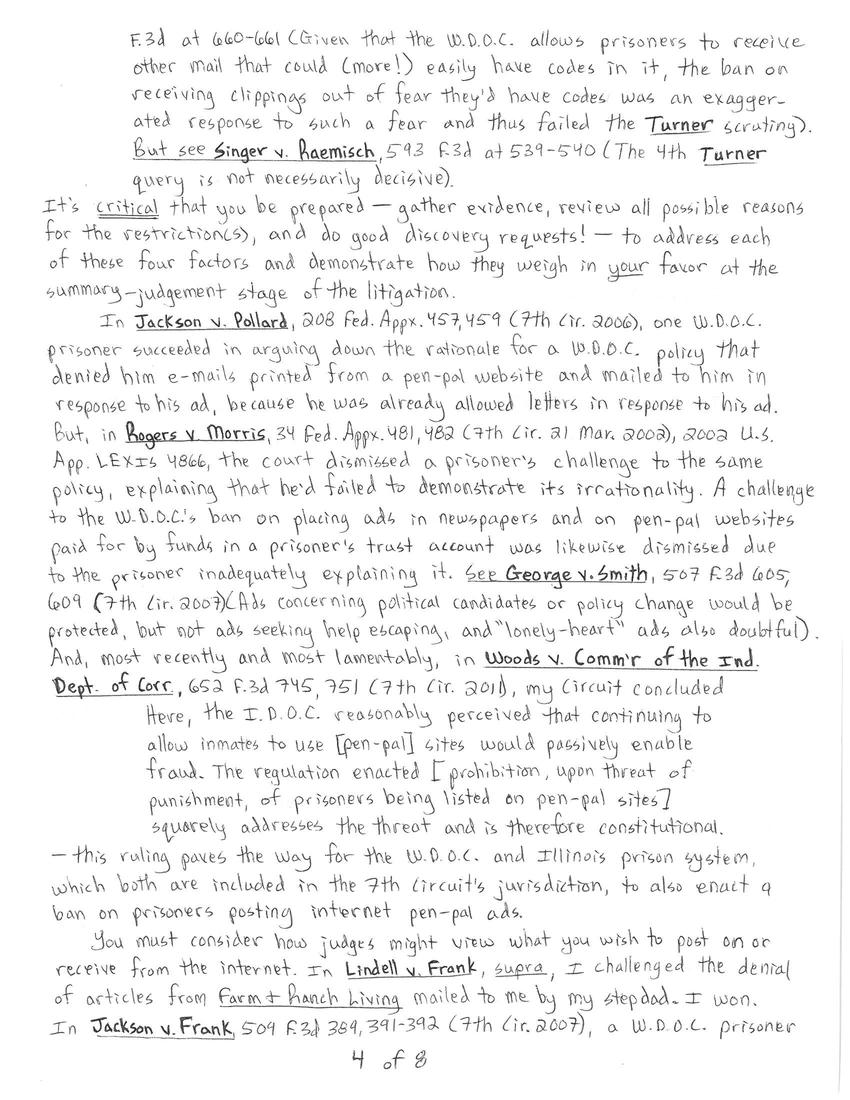

You must consider how judges might view what you wish to post on or receive from the internet. In Lindell v. Frank, supra, I challenged the denial of articles from Farm + Ranch Living mailed to me by my stepdad. I won. In Jackson v. Frank, 509 F.3d 389, 391-392 (7th Cir. 2007), a W.D.O.C. prisoner challenged the denial of a fan-club photo of Jennifer Aniston, based on a policy banning "commercial photos". He lost, and the judges nearly ridiculed his claim. Judges already assume we're animalistic morons - why confirm this by suing over bubblegum bullshit? Sue over incidents that compel sympathy and respect; change the policy, then - if you must - go after the less admirable material you want. I'm certain that had Jackson sued over the denial of "commercial photos" of scenery or animals ordered from National Geographic, he'd have overturned the policy.

Cases Ruling on Prisoners' Access to Internet Printouts and Postings on Websites

The first case I became aware of (Only recently did I stumble upon Rogers v. Morris, discussed earlier. No loss, as it was a pathetic failure in attacking the WDOC's ban on 'net copies.) that challenged prison staff's denial of materials printed from a website is Clement v. Cal. D.O.C., 220 F. Supp. 2d 1098 (N.D. Cal. 2002). He won, for much of the same reasons that I won in Lindell v. Frank. Clement was affirmed on appeal, 346 F.3d 1148, 1152 (9th Cir. 2004), and is a great example of how convicts can and must effectively argue the Turner factors.

After Clement came Canadian Coalition Against the Death Penalty v. Ryan, 269 F.Supp.2d 1199, 1203 (D. Ariz. 2003), where a website publisher and a prisoner sued and won summary judgement in a case that challenged Arizona's policy of punishing prisoners whom had their info posted on websites by a third party. No appeal was filed. It's another good example of how to argue the Turner factors successfully.

Clement, sent to me by David Fathi of the ACLU's National Prison Project, helped me defend my win in Lindell v. Frank, which in turn helped another prisoner end the W.D.O.C.'s ban on printouts from websites, see West v. Frank, 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5024 *12-13, 23, W.D. Wis. Case No. 04-C-173-C, 25 Mar. 2005 summary judgement order, 2005 WL 701703 (W.D.O.C. mooted West's claims by lifting its ban on printouts from websites, defendants given qualified immunity on West's claims for monetary award).

One of the claims the W.D.O.C. inmate plaintiff tried to press in George v. Smith, W.D. Wis. Case No. 05-C-403-C, concerned being denied the use of his funds in his prison account to purchase ads on a pen-pal website and in personal classifieds in newspapers. W.D. Wis. Chief Judge Crabb rejected this claim at the P.L.R.A. screening stage, reasoning: Plaintiff's allegation suggests that he was seeking permission to correspond with anyone who might answer his personal ad. The First Amendment does not require prison officials to allow inmates this degree of freedom in choosing their correspondence partners. Plaintiff's allegation does not allege a violation of his rights under the First Amendment. Id. 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 16139, 2 Aug. 2005 order *20, affirmed by 507 F.3d 605, 609 (7th Cir. 2007). The fact that Mr. George was an O.G. pedophile, though unmentioned by any of the judges, may have influenced their decisions; because District of Columbia v. Heller, supra at id. and Pell v. Procunier, supra at id., support his proposed Free Speech claim (And, Wis. Admin. Code DOC 309.04 Inmate mail, at sub. (a)(c) states: "The department shall permit an inmate to correspond with anyone.), while King v. Fed. B.O.P., 415 F.3d 634, 637-638 (7th Cir. 2005) revealed that prisoners have a due process right to decide how to use their assets, including money. The forenoted ruling in Jackson v. Pollard, 208 Fed. Appx. 457 almost seems to oppose the conclusion in George; but in Jackson v. Pollard the prisoner was specific as to what he was suing about and pointed out the inconsistencies in the ban that showed it to be irrational. Wisconsin's Admin Code DOC 309.04(a)(c) may give us just such an inconsistency to prevent a blanket ban on placing pen-pal ads, or at least allow us to receive mail from such ads.

Lewis v. M.D.O.C., W.D. Mo. Case No. 09-4167-CV-C-SOW and Argentino v. Dormire, W.D. Mo. Case No. 09-4217-CV-C-SOW appear to be two lame attacks on the M.D.O.C.'s policy that threatens to punish prisoners with ads on pen-pal websites. It appears from the summary-judgement orders in the cases - i.e. 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 150673 and 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 407, respectively - that these prisoners never even opposed the M.D.O.C.'s motions for summary judgement. I hope their fellow convicts ask them about that "strategy". The M.D.O.C. DOES allow prisoners to post blogs and other non-pen-pal information.

Along with Woods v. Comm'r of the Ind. Dept. of Corr., 652 F.3d 745 (7th Cir. 2011), noted earlier, there is another ugly prison pen-pal case, Perry v. Fla. Dept. of Corr., 664 F.3d 1359 (11th Cir. 2011), brought by the operator of www.writeaprisoner.com. As both were resolved using the Turner standard, I will explain below how the courts resolved each of the four questions in each case.

1) In Woods, at 749, the Circuit found a valid rational connection to the legitimate concern (based on an investigation by the head of the I.D.O.C., which revealed multiple I.D.O.C. prisoners misrepresent themselves on internet pen-pal ads and pen pals had been defrauded) of denying prisoners access to potential fraud victims. Perry, at 1366 found the ban on pen-pal ads on the internet also to be rationally related to preventing fraud, a legitimate concern.

2) Woods, at 749, noted that prisoners could still obtain pen pals met through their attorneys, publications, and through prisoner-support groups that visited prisons. Perry, at 1366-1367, noted that one-to-one pen-pal matching services (e.g. Christian Pen Pals, P.O. Box 11296, Hickory, N.C. 28603) were approved (they minimize risk of fraud), along with other means of meeting new people (e.g. through other prisoners).

3) At 750, Woods found that it would consume too many resources to monitor pen-pal ads and resultant correspondence to prevent frauds and create the risk of fraud, while Perry, at 1366-1367 found the same.

4) Finally, Woods at 751 noted "The regulation... squarely addressed the threat and is therefore constitutional." Perry, at 1367 analyzed the fourth factor more deeply, but concluded that other Florida laws were not enough to prevent prisoners from scamming pen pals.

Keep in mind that neither Woods nor Perry concerned bans on blogging or, at least as I recall, posts on social-networking sites like Facebook and MySpace. Further, in my circuit, George v. Smith, as explained earlier, has at least hinted that ads concerning political action are protected. In Cassels v. Stalder, 342 F.Supp.2d 555, 564-567 (M.D. La. 2004), one court held that it violated the First Amendment to punish a prisoner because his mom posted his gripe about being denied medical care on a website.

Where we're at presently is that Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, Missouri, and Indiana have restrictions on prisoners' internet access that ranges from prohibiting receipt of e-mails printed and mailed to prisoners up to total bans on publishing prisoners' info on the internet. These restrictions are somewhat ironic, given that the most widespread and heavily populated prison system in the U.S. - the Federal Bureau of Prisons - has no such restrictions and even provides its captives with computer access in his libraries, so captives can send and receive e-mails (I'm sure the B.O.P. uses a kick-butt program to screen e-mails for plots to escape, smuggle contraband, etc.).

Given that snail mail is dying and the pervasiveness of internet access as well as the convenience of searching and storing electronic media vs. paper media, it is inevitable that prisoners will obtain more access to the internet, including pen-pal websites, although prison systems may still try to scare off prospective audience members by use of a digital watermark like the inked version stamped on the back of all W.D.O.C. prisoners' mail: This letter has been mailed from the WISCONSIN PRISON SYSTEM.

Anyone may contact me for further information or assistance with this or other legal matters, including mail directly from other convicts, at:

Nate A. Lindell (DOC#, optional, is 303724)

P.O. Box 9900

Boscobel, WI

53805-0901

However, unless provided with an embossed-postage SASE or you order embossed envelopes for me from 1-800-236-2611, www.JLMarcusCatalog.com, I can't guarantee a reply.

P.S. I'm curious as to hear about the creative ways that internet companies will come up with to get around prison systems' bans on pen-pal ads. Maybe members only sites, requiring a password to view profiles, or at least to view advertisers' contact info? Prisoners want the exposure, and websites want money, so something must give.

I have profiles posted on writeaprisoner.com and prisonpenpals.com.#

Copyrights - entirely reserved by the author. Prisoner-rights activists, prisoners, and students and instructors/professors may copy, print off, and republish this document for use in activism, litigation, personal study, classwork, so long as the author's by-line and the URLs for his blog are credited as the source.

Someone e-mail this to dfathi@npp-aclu.org + any prisoner websites.

Other posts by this author

|

2025 jul 19

|

2025 apr 16

|

2025 mar 3

|

2024 sep 11

|

2024 aug 24

|

2024 aug 20

|

More... |

Replies