Transcription

SJRA ADVOCATE

March 2013 Published by Barbara Brooks, Sentencing and Justice Reform Advocacy (SJRA) Vol.5. Issue 1

P.O. Box 71, Olivehurst, CA 95961 530-329-8566 YesWeCanChange3X@aol.com www.SJRA1.com

Printing provided by Carole Urie, Returning Home Foundation, Laguna Beach, CA 92651

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Mr. Governor, Realign yourself with the Courts!

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Looking Past the Hype:

10 Questions Everyone Should Ask about California's Prison Realignment

Joan Petersillia, Ph.D.

Adelbert H. Sweet Professor of Law,

Stanford Law School

Jessica Snyder

J.D. candidate, Stanford Law School

Used with permission of Joan Petersillia;

Forthcoming in The Journal of California

Policy and Politics, 2013

On October 1, 2011, the Public Safety Realignment Act (Assembly Bill 109) went into effect and comprehensively changed the way California manages its non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual offenders. This dramatic piece of legislation resulted from the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Plata declaring California's prison conditions to violate the 8th Amendment against cruel and unusual punishment, and at a time when California faced a projected $26 billion state budget deficit. AB 109 not only shifted vast discretion for managing these lower level offenders from the state to the county, but also allocated over $2 billion in just the first two years for local programs. To date, over 100,000 offenders have had their sentences altered due to AB 109. California's Realignment is the biggest penal experiment in modern history. Despite this fact, little has been done to consider Realignment's impact broadly, or to evaluate its statewide impact on crime, incarceration, justice agencies, costs, or offender recidivism. Unlike some previous California initiatives, the Legislature allocated no funding for an independent statewide evaluation or cost-benefit analysis.

To understand how Realignment impacts criminal justice broadly, we should be asking ten essential, interdependent questions: (1) Have prison populations been reduced and medical care sufficiently improved to raise prison medical care to a constitutional level? (2) What is its impact on victim safety and victims' rights? (3) Will more offenders participate in evidence-based treatment programs, and will their recidivism be reduced? (4) Will there be equitable sentencing and access to treatment across counties? (5) What is the impact on jails (e.g., crowding, conditions, and litigation)? (6) What is the impact on police, prosecution, defense, and judges? (7) What is the impact on probation and parole? (8) What will be the impact on crime rates and community life? (9) How much will Realignment cost, and who will shoulder the cost? (10) Has the total number of people under criminal justice supervision increased?

In this brief and an accompanying article,¹ we proceed as follows: First, we provide a brief overview of the key components of AB 109; and second, we discuss in turn the ten critical questions that everyone should be asking about California's Realignment. For each of these questions, we attempt to identify the important issues at stake. Additionally, we provide analysis and data where available to begin the process of answering these important issues at stake. Additionally, we provide analysis and data where available to begin the process of answering these important questions.

Key Components of California's Public Safety Realignment Act (AB 109)

Realignment Population

While AB 109 is comprehensive and complex, it primarily affects three major groups:

1. LOWER-LEVEL FELONY OFFENDERS whose current and prior convictions are non-violent, non-sex-related, and non-serious (referred to as "non-non-non's) will now serve their sentence under county jurisdiction rather than in state prison. Realignment amended about 500 criminal statutes to eliminate the possibility of a state prison sentence upon conviction. Some of the realigned crimes include, for example, commercial burglary, possession of marijuana for sale, forgery, and vehicular manslaughter.

2. RELEASED PRISONERS whose current offense qualifies as a "non-non-non" offense will be diverted to the supervision of county probation departments under "Post Release Community Supervision (PRCS)." Pre-Realignment, state parole agents supervised these individuals released from state prison.

3. PAROLE AND PROBATION VIOLATORS will generally serve their revocation terms in county jail rather than state prison. Before Realignment, individuals released from prison could be returned to state prison for up to a year for violating the technical conditions (e.g., positive drug test) of parole supervision.

COMMUNITY CORRECTIONS PARTNERSHIP

Comprised of the Chief Probation Officer as chair, District Attorney, Public Defender, Presiding Judge, a Chief of Police, Sheriff, and a representative from social services, the Community Corrections Partnership (CCP) for each county was responsible for developing the county's Realignment implementation plan, including allocating available funding to government and/or community agencies and services.

FUNDING FORMULA

In the first fiscal year of Realignment, 60% of each county's funding allocation was based on the county's historical average daily state prison population ("ADP") of persons convicted of non-violent offenses from the particular county; 30% was based on the size of each county's adult (18 to 64) population; and the remainder (10%) was based on each county's share of funding under the California Community Corrections Performance Incentives Act of 2009 (SB 678). SB 678 was based on a county's ability to divert adult probationers from prison to evidence-based programs.

In the second and third years of Realignment, counties were given the best result among three options in which funding was based on: (1) the county's adult population ages 18 to 64; (2) the status quo formula of FY 2011-12; or (3) weighted ADP. Over a quarter of counties benefited from the new weighted ADP option, in some cases almost doubling what they would have received had their allocation been based on the county population.

COUNTY DISCRETION

Realignment shifted unprecedented discretion to California's 58 counties. How did counties choose to spend the available funds? We analyzed every county's proposed 2011-12 spending plan and found that while there was a great deal of variation, the average funding allocation for the first year of Realignment was as follows:

• 35% to the sheriff's department

• 34% to the probation department

• 12% for programs and services, such as substance abuse and mental health treatment, housing assistance, and employment services

• 19% unallocated/reserved funds

We also found that 35% of all the allocated AB 109 money in the first year was earmarked for probation and sheriff staff salaries. Virtually all of the 58 county plans indicated they intended to use evidence-based programming, but interestingly, only five counties dedicated more than one paragraph describing what they meant by this.

We are now analyzing data for 2012-13 and observe that agencies are beginning to invest more of their available funds in evidence-based programs; our forthcoming research will highlight some of the more innovative Realignment approaches.

QUESTION 1: HAVE PRISON POPULATIONS BEEN REDUCED AND MEDICAL CARE SUFFICIENTLY IMPROVED TO RAISE PRISON MEDICAL CARE TO A CONSTITUTIONAL LEVEL?

The size of the prison population is the outcome that everyone is watching.

• On October 1, 2011, the prison population was 160,295, more than double what the prison system was designed to hold.

• In just the first three months after Realignment, the number of inmates in California prisons dropped by 11,000 - a decline of nearly 10% - an astonishingly steep decline.

• By the end of 2012, California's prison population had dropped by another 15,000, reaching 132,619 prisoners, its lowest level in 17 years.

The nature of the prison population has changed significantly. In the year following Realignment, almost half of all admissions to prison were for violent crimes - a 62% increase relative to 2010. On January 14, 2013, Governor Brown called a press conference to declare California's long running prison crisis over. He argued that the State's prisons were now constitutional at the current level of 133,000 inmates and 150% of design capacity.

However, with all the focus on the size of the prison population, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that the motivating cause of the judicial order was not overcrowding itself, but the inadequacy of the medical and mental health care provided to prisoners. Less crowding will not in and of itself improve health care. Improving health care requires the construction of new specialized space to provide health care and the hiring of trained medical professionals. San Quentin prison opened a new hospital in 2010, and a new California Health Care Facility in Stockton will open in 2013, providing in-patient mental health care.

The size of the prison population is the outcome that everyone is watching. Right now, the prison system is reaping the full benefits of Realignment, primarily due to the decline in technical violations being admitted to prison. But, prison admissions over time remain unknown - mostly because counties have a great deal of discretion in the new AB 109 system. Depending on how counties exercise that discretion, the decline in state prisoners may not last. In fact, the decline in prisoners stalled by September 2012 at about 133,000.

QUESTION 2: WHAT IS REALIGNMENT'S IMPACT ON VICTIM SAFETY AND VICTIMS' RIGHTS?

Although the focus of AB 109 is clearly on what to do with offenders, Realignment significantly impacts crime victims and witnesses. Despite the fact that victims in California have some of the strongest constitutional rights of any state in the nation, victims' rights and safety is a significant concern that has, for the most part, gone unmentioned in Realignment discussions.

Realignment's impact on crime victims is multifaceted. More felons may be granted early release due to jail overcrowding, and these early releases may increase the risk of citizens becoming crime victims. On the other hand, if counties divert offenders to more effective treatment and work programs, thereby reducing their recidivism, overall victimization rates will decline.

Realignment poses several potential problems for victims' rights in California:

1. Realignment may threaten several due process and statutory rights guaranteed to crime victims under Marsy's Law, the California Victims' Bill of Rights Act. For example, Realignment has seriously diminished crime victims' access to the notice that Marsy's Law requires, mostly because it is not clear who is responsible for providing that notification and when.

2. Realignment may reduce the ability of victims to collect restitution. Under the former system, victims received their restitution payments through the parole system and through prison work programs. Most counties currently have no system in place to garnish wages in a similar way.

Such legal and policy conflicts could result in significant litigation challenging various applications of Realignment. Victims advocates have suggested that they be granted a voting seat on the Community Corrections Partnership in each county, and that the legislature needs to clarify which county agency is responsible for implementing which due process rights post-Realignment.

QUESTION 3: WILL MORE OFFENDERS PARTICIPATE IN EVIDENCE-BASED TREATMENT PROGRAMS, AND WILL THEIR RECIDIVISM BE REDUCED?

At its core, Realignment is designed to increase offender treatment and program participation, and therefore, reduce recidivism. Counties have a far greater stake than the state does in rehabilitating offenders, because counties are responsible for their absorption after they are released. Those going to county jail will almost surely return to the same community after serving their sentences.

But for Realignment to make an impact on recidivism, three things must happen. The first two are within the counties' control. FIRST, offenders must have the opportunity to participate in treatment programs, and SECOND, the program's design must incorporate elements consistent with the principles of effective correctional intervention. Research has shown that programs incorporating these principles reduce recidivism. The literature suggests that a realistic reduction in recidivism from such programs is about 10% overall. California developed the Correctional Program Assessment Process, a checklist of items that must be present for a program to qualify as "evidence-based." If offenders aren't participating in these programs, we shouldn't expect recidivism reduction. The THIRD necessary element to reducing offender recidivism is less within the counties' control: Offenders must want to take advantage of the programs offered. Counties can make more evidence-based programs available, but if the offender lacks the motivation to take advantage of them, recidivism will not be reduced.

To be sure, there are multiple counties using their Realignment dollars to innovate. Most probation departments are now administering risk and need assessments. Thirty-one counties are funding Day Reporting Centers, and other counties have launched one-stop hubs for realigned clients to better access services. Interestingly, Realignment has also spurred non-traditional agencies to embrace rehabilitation. District attorneys in at least two counties have hired alternative sentencing planners to match defendants with community programs, and sheriffs in several counties have initiated reentry programs.

QUESTION 4: WILL THERE BE EQUITABLE SENTENCING AND ACCESS TO TREATMENT ACROSS CALIFORNIA'S 58 COUNTIES?

Under Realignment, judges now have widespread discretion to impose a jail term (for the same sentence length that the offender would have received pre-Realignment), a community based alternative, or some combination of jail and mandatory supervision. This latter option is known as split sentencing, where the judge imposes a sentence that combines county jail time with mandatory probation supervision.

Sentencing disparity across counties has likely increased under Realignment. In the first nine months of its implementation, over 21,500 felony offenders were sentenced to local jail terms as non-non-non felony offenders. Approximately 5,000 or 23% of those offenders received split sentences. The remaining 77% were sentenced to a straight jail sentence, without mandatory supervision to follow. Once their jail term is served, they are released, and not subject to supervision post-incarceration.

Counties vary significantly with respect to the use of split sentencing. Judges in Los Angeles, with roughly a third of all felons in the state, impose split sentencing in just 5% of it's Realignment cases, whereas judges in Contra Costa impose split sentences in 84% of its cases. As discussed below, counties also vary dramatically in the lengths of sentences imposed.

The danger of the unfettered discretion afforded under Realignment may lead to greater sentencing disparities. Remember that California adopted its current determinate sentencing. As a general matter, defendants with similar criminal records found guilty of similar crimes should receive similar sentences. Of course, this ideal has never been fully realized, but we should be diligent to assure that Realignment does not increase the impact of extralegal factors, such as race, income, and geography, on sentencing outcomes.

QUESTION 5: WHAT IS REALIGNMENT'S IMPACT ON JAILS, INCLUDING CROWDING, STAFF SAFETY, INSTITUTIONAL VIOLENCE, AND THE PROVISION OF MEDICAL CARE?

The most immediate impact of Realignment was to exacerbate jail overcrowding. Many of California's 58 county jails were already dangerously overcrowded when Realignment went into effect.

• 17 county jails are operating under a court ordered population cap

• 20 additional county jails have a self-imposed cap on their jail populations

Realignment caused an immediate increase in jail inmates. By March 2012, the California jail population reached 78,796 inmates, 11% higher than the same period in 2011. Sheriffs reported being forced to release 11,000 inmates early each month due to lack of space.

The legislature recognized the need to add jail capacity and passed Assembly Bill 900 in 2007, allocating $1.2 billion in state matching funds for jail expansion. The AB 900 money will increase California's overall jail capacity by about 9,200 inmates.

But it isn't just the inmate population increases that worry jail managers. Equally problematic are the very long sentences being imposed under Realignment, the more serious nature of inmates being sent to jail, and the medical and mental health care needs of the inmate population. A recent study by the California State Sheriffs' Association found that since AB 109, 1.153 inmates (about 3% of all those sentenced) have been sentenced to serve over five years in county jail.

Counties face a dilemma. While the State is providing construction dollars, the costs of new jails are substantial, with construction accounting for just 10% of the total cost of a jail over its lifetime. But if they don't expand jail capacity, they risk huge litigation costs due to crowding and inadequate care. In fact, the Prison Law Office sued Fresno County on behalf of four jail inmates who say jail conditions there violate their 8th amendment rights. But if counties use their AB109 funding simply to build more jail beds, they will have missed an opportunity to dedicate resources to rehabilitation. If Realignment becomes just a jail expansion program, then we will ultimately have created a corrections system that costs more than it does today with little positive benefit.

QUESTION 6: WHAT IS REALIGNMENT'S IMPACT ON POLICE, PROSECUTORS, DEFENSE ATTORNEYS AND JUDGES?

There are myriad ways that Realignment will impact law enforcement and court systems. These impacts will be highly variable from county to county. Whether Realignment works or not will significantly depend on how local authorities handle prosecutorial charging, plea-bargaining, and sentencing. AB 109 eliminates the technical parole revocation route to prison, and it also reduced by 50% the length of minimum post-prison supervision (from 13 to 6 months). A possible unintended consequence is that prosecutors will feel more pressure to file new criminal charges, and if felons are convicted, those charges will result in longer prison terms than the previous 12-month maximum parole revocation terms.

Additionally, most believe that Realignment increases defense attorneys' leverage in negotiations with prosecutors. Perhaps the most frequently mentioned source of defense attorneys' newfound power is the removal of prison from the host of options facing a "non-non-non" defendant. Essentially, prosecutors used to induce pleas by offering to take prison off of the table if the defendant agreed to plead guilty.

Thus; one unintended consequence of AB 109 might be an increased trial rate. Any increase will put pressure on staffing in district attorneys' offices, on the available space and staff resources of and caseloads of Superior Courts, and on the budgets for indigent defense representation.

Another effect of AB 109, possibly a beneficial one, is that judges might take jail burdens into account when exercising sentencing discretion. If so, this would be an example of officials at the county level internalizing costs of incarceration that had been previously imposed on the state.

One very important consequence of AB 109 for judges will not actually come to pass until July 2013, at which time trial judges will become the deciding officials on large numbers of new revocation cases.

QUESTION 7: WHAT IS REALIGNMENT'S IMPACT ON PROBATION AND PAROLE?

It is safe to say, that the success of Realignment hinges on the performance of probation - and in many ways, the future of California hinges on the success of Realignment. Probation is fundamental since they are the agency primarily charged with implementing "evidence based" programs. Parole too has a critical - albeit more nuanced - role to play in Realignment's success.

Both agencies must now supervise an increasingly serious offender population. Line staff in both agencies echo the same sentiment: they are being asked to do too much, too fast, with too little.

Realignment provides California's probation system an opportunity to test whether it can reduce recidivism through evidence-based programs. Probation has always supervised two-thirds of Californians under correctional supervision but never received the resources commensurate with their responsibilities. Historically, for every dollar spent on prisons, the U.S. spends just 6 cents on probation and parole. Realignment balances the scales slightly by investing in community-based treatment.

One of the biggest points of controversy is the serious risk level of the population now being supervised by probation. Assignment to PCRS is determined only by the current prison conviction offense regardless of prior record, mental health status, or in-prison behavior. This significantly alters probation's caseload and creates a higher-need, higher-risk population to supervise.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) is tracking the risk levels of released prisoners. Their data reveal that in the first year after Realignment, prisoners sent to PCRS were more likely to have a "high" California Static Risk Assessment score. 55% of PCRS offenders score "high" for risk of recidivism compared with 44% of those retained on state parole. Historically, 80% of "high risk" California prisoners were rearrested during the 3 years following their release, and about a third of those arrests were for a violent felony.

QUESTION 8: WHAT WILL BE REALIGNMENT'S IMPACT ON CRIME RATES AND COMMUNITY LIFE?

Will Realignment increase or decrease crime rates, or have no negligible impact? Potentially, crime could rise as offenders serve shorter sentences and more of them are on the streets. On the other hand, Re-alignment could contribute to a decrease in crime if counties apply evidence-based programs that have been found in other states to reduce recidivism.

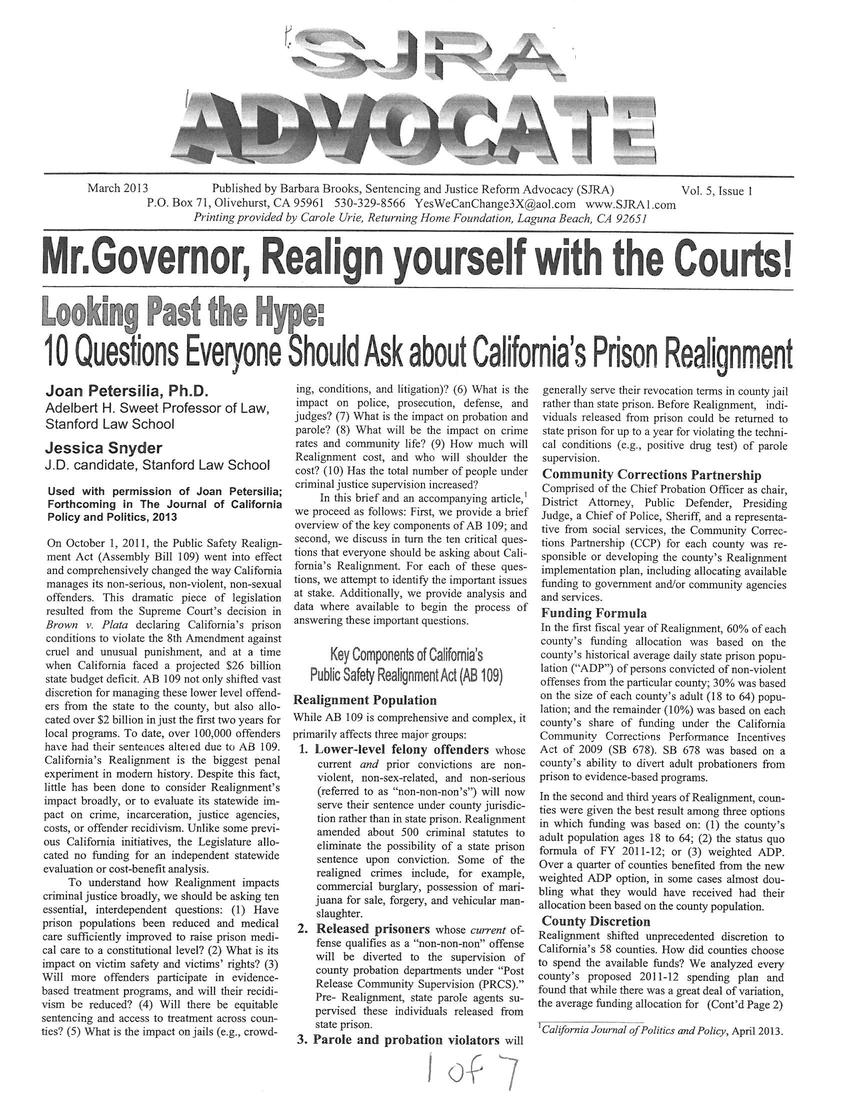

The Public Policy Institute of California is studying Realignment's impact on crime and has concluded that statewide violent crime continues to decline but that the downward trend in property crime is ending (Figure 1). But correlation doesn't equal causation.

Many law enforcement believe that the lack of a "hammer" or threat of a prison sentence is undermining deterrence and will ultimately increase crime. But not all share these predictions. Los Angeles county Sheriff Lee Baca "believes his deputies can do a better job than the state when it comes to managing 'low-level offenders.'"

These differing viewpoints amongst the counties demonstrate how important accurate measurement of crime rates and recidivism will be to assessing Re-alignment's success. This issue will likely determine public support for Realignment, yet this issue is in-credibly difficult to measure accurately.

QUESTION 9: HOW MUCH WILL REALIGNMENT COST, AND WHO WILL SHOULDER THE COST?

Before the ink was dry on AB 109, everyone was complaining about the funding. Many counties said the money was insufficient and that the formula for determining how much each county received was poorly conceived. Other counties feared that the state's financial commitment to the counties would be short-lived. Proposition 30 has now provided constitutional protection for Realignment funding. But how much is Realignment really costing us? And how is the money being spent? What have we gotten for our investment?

It is hard to get a full accounting of how much money the State is investing in Realignment, as several different bills fund portions of it. According to California's Department of Finance, Realignment will reduce the state inmate population by about 40,000 inmates (roughly one-fourth of the total inmate population) upon full implementation by 2014-15. The state parolee population is projected to decline by 77,000 parolees (roughly three-fourths of the total parole population) in 2014-15. The Legislative Analyst's Office suggests that this reduction in inmate and parolee population resulted in a state savings of about $453 million in 2012, and the savings will increase to $1.5 billion by 2014. The State argues the cost savings are much higher, as they have avoided the cost of building and operating new prisons.

But there are reasons to believe that these corrections costs are too narrowly conceived, as they don't account for long-term social and systemic costs. Additional costs should (minimally) include increased social service, law enforcement, jail, and court costs. Moreover, this accounting does not include the long-term cost benefits if offenders don't recidivate and become productive members of society.

Taxpayers should demand a full accounting - and a statistical model that keeps track of the state versus county costs. If counties fall short of their goal for Realignment, it's important for policymakers to know whether the problems might be traced to budget choices by state and local authorities.

QUESTION 10: HAS THE TOTAL NUMBER OF PEOPLE UNDER CRIMINAL JUSTICE SUPERVISION INCREASED?

The term "correctional control" describes the total corrections population under supervision at any given time. The total consists of all offenders supervised on probation and parole as well as those incarcerated in prisons and local jails. Tracking such data will show us whether we have downsized state prison and parole populations while simultaneously increasing jail and probation populations. In ten years, will more people be locked up and on supervision than in 2011 when Realignment went into effect? If the correctional control rate increases, we can conclude that we haven't effectively implemented programs that reduce recidivism, but simply changed the address where offenders live and report - from prison to jail, and from parole to probation.

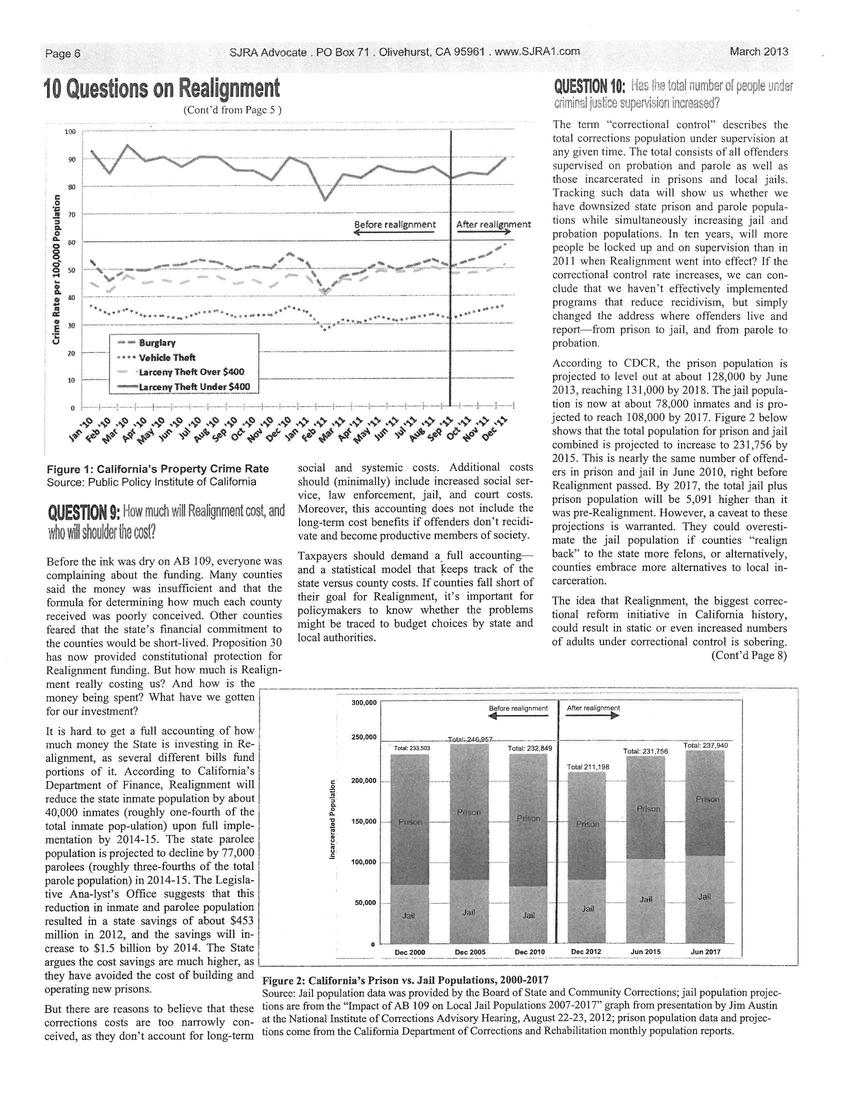

According to CDCR, the prison population is projected to level out at about 128,000 by June 2013, reaching 131,000 by 2018. The jail population is now at about 78,000 inmates and is projected to reach 108,000 by 2017. Figure 2 below shows that the total population for prison and jail combined is projected to increase to 231,756 by 2015. This is nearly the same number of offenders in prison and jail in June 2010, right before Realignment passed. By 2017, the total jail plus prison population will be 5,091 higher than it was pre-Realignment. However, a caveat to these projections is warranted. They could overestimate the jail population if counties "realign back" to the state more felons, or alternatively, counties embrace more alternatives to local incarceration.

The idea that Realignment, the biggest correctional reform initiative in California history, could result in static or even increased numbers of adults under correctional control is sobering.

While the overall incarceration population in California may not change over time, Realignment could still be considered to have achieved its aims of both satisfying the Plata court order's requirement for the state prison population to more closely match its capacity, and by keeping offenders closer to their communities while investing in evidence-based treatment programs. In meeting both of these goals, California could simultaneously minimize costs and maintain - or even - improve public safety.

CONCLUSION

California is at a crossroads, a time of rethinking possibilities. Motivated by a crisis, AB 109 provides an opportunity for California to be smart in its approach to crime. The importance of California's Realignment experiment cannot be overstated. It will test whether the nation's largest state can reduce its prison population in a manner that increases public safety and better utilizes taxpayer dollars. Realignment's significance is precisely why it needs to be closely monitored. Answering these questions and many more will help state and local officials learn what is and isn't working, what problems were encountered in implementation, and which offenders benefited from the program. Ultimately, answering these questions will tell us whether the accomplishments were worth the resources invested.

_____________________________________________

¹California Journal of Politics and Policy, April 2013

Figure 1: [Chart showing property crime rates before Realignment and after] California's Property Crime Rate; Source: Public Policy Institute of California

Figure 2: California's Prison vs. Jail Populations, 2000-2017

Source: Jail population data was provided by the Board of State and Community Corrections; jail population projections are from the "Impact of AB 109 on Local Jail Populations 2007-2017" graph from presentation by Jim Austin at the National Institute of Corrections Advisory Hearing, August 22-23, 2012; prison population data and projections come from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation monthly population reports.

Criminal Justice, Drug Offenses, and Mental Illness

By Maureen Murdock, PhD

Part Two of Two Parts

The Incarceration of the Mentally Ill: A Poor Substitute for Treatment

Mentally ill inmates are nearly always jailed for behaviors related to their illness. But the vast majority of Americans with a mental health condition are not violent. In fact, just 4% of violent crimes are committed by individuals who suffer from a serious mental illness. Yet, nationally, they account for about one-sixth of the prison population. A staggering 45% of our mentally ill citizens are incarcerated: 24% of state prisoners and 21% of local jail prisoners. The ratio appears to be higher among three-strike lifers in California. According to a 2011 analysis of state data by Stanford Law School's Three Strikes Project, nearly 40 percent of these inmates qualify as mentally ill and are receiving psychiatric services behind bars [Brent Staples, "California Horror Stories and the 3-Strikes Law", New York Times, 11/24/12).

Even before the recent ballot initiative, the clinic's law students had overturned the life sentences of 26 people, based on newly discovered evidence or inadequate assistance of counsel, as when defense lawyers failed to present evidence of a client's mental illness.

Asked about the relationship of mental illness and three-strikes prosecutions, Michael Romano, director of the Stanford project, responded, "In my experience, every person who has been sentenced to life in prison for a non-serious, nonviolent crime like petty theft suffers from some kind of mental illness or impairment - from organic brain disorders, to schizophrenia, to mental retardation, to severe P.T.S.D.", or post-traumatic stress disorder. Nearly all had been abused as children, all had been homeless for extended periods, and many were illiterate. None had graduated from high school.

In other words, these discarded people have been made to bear the brunt of this brutal law without risk of public backlash. Among the more horrifying cases investigated by the Three Strikes Project is that of 55-year-old Dale Curtis Gaines, who suffers from both mental retardation and mental illness. He has never committed a violent crime, but is serving a life sentence for receiving stolen property. His first two strikes, daytime burglaries of empty homes during which he was unarmed, appear to have involved thefts valued at little more than pocket change.

At the time of his third strike, for receiving stolen computer equipment, Mr. Gaines was getting Social Security and disability benefits because of mental illness and retardation. His mental health history, readily available in the prison record, would probably have been recognized as a mitigating factor and prevented him from being so harshly sentenced. But, according to court documents, his public defender presented no evidence about his disability.

In 2010, 12 years after Mr. Gaines was convicted, the prosecutor who handled the case but by then had left the district attorney's office wrote to him in prison, expressing regret and offering help if he wished to appeal. The Stanford students also noticed his case and are now trying to free him. (Brent Staples, "California Horror Stories and the 3-Strikes Law", New York Times, 11/24/12).

Governor Jerry Brown recently declared that California has one of the finest prison systems in the United States and that inmates get "far better" medical care, including mental health care, in prison than those outside. I wonder if he has ever visited any of the prisons in California. I think his statement is not about how good mental health treatment is in prison but about the lack of adequate mental health treatment on the outside.

California was mandated in 2011 by the federal courts to reduce the number of inmates. Brown said the number of inmates locked in state prisons has been reduced by 42,000 since 2007 down from 161,000 to 119,000. More than half of the reduction is due to his "realignment program", the shift of incarcerating newly convicted, low-level felons from state prisons to county jails. The federal courts have ordered the state to reduce its prison population by an additional 9,000.

Governor Brown claims that isn't necessary. He maintains that the gyms in prison are no longer clogged with bunks; they're full of basketballs and hoops. "They are not overcrowded", he said. I'd like to know what prisons he's visited. My son is housed in H-unit, at San Quentin, a large open dorm with 100 bunk beds for 180 inmates. The realignment program is a shell game; inmates are shipped out to jails to meet the reductions and then shipped back in.

Special Master Matthew Lopes, a court-appointed monitor, has criticized Governor Brown's assessment of the reductions in CA prisons. Reported in the Los Angeles Times by Paige St. John, ("Oversight of state prisons needed", Paige St. John, Los Angeles Times, 1/19/13) Lopes has said that Gov Brown's quest to end judicial oversight in state prisons is "not only premature but a needless distraction" from improving care for mentally ill inmates.

Lopes cited dozens of suicides in 2012, long isolation instead of treatment, and lapses in care as reasons federal oversight should continue. Lopes filed his assessment with the US District court after he visited two-thirds of California's 33 prisons. He determined that only Sacramento - not individual wardens - could fix the underlying problems with mental health treatment in the corrections system.

He writes, "Any attempt at a more abrupt conclusion to court oversight would be not only premature but a needless distraction from the important work that is being done in the quality improvement project" ("Oversight of state prisons needed", Paige St. John, LA Times, 1/19/13).

He was especially critical of the suicide rate in California prisons. There were at least 32 suicides in state prisons last year, averaging one every 11 days. That translates to almost 24 suicides per 100,000 inmates, a 13% increase over 2011 and well above the national suicide rate of 16 deaths per 100,000 prisoners.

The state's high suicide rate prompted a 2010 court order to adopt suicide prevention practices. Lopes found that fewer than 1 out of 4 prisons hold suicide prevention team meetings as required by law and only 3 prisons complied with the requirements for 5-day follow-ups with inmates discharged from crisis care.

Lopes also found that all 11 outpatient care hubs in the prison system still conduct inmate counseling sessions in public, despite the need for confidential settings. 10 of those hubs fail to offer at least 10 hours of structured therapy per week, which Lopes felt should be a priority.

A training program designed to help prison guards interact with mentally ill inmates and mental health providers showed no improvement in use-of-force incidents or missed treatment sessions. Lopes also documented instances of mentally ill inmates being housed for extended periods in isolation units. At Kern Valley State Prison, mentally ill offenders had been isolated as long as 292 days. To comply with terms of the special master, that time period should be no more than 30 days.

Families of mentally ill inmates have expressed their frustration. Blanca Gonzalez said her 31-year-old son's mental state has deteriorated since his incarceration. He was put into segregation on Thanksgiving and not moved to a psychiatric unit until mid-January. She said, "I am watching my son die in front of me and no one seems to care." ("Oversight of state prisons needed", Paige St. John, LA Times, 1/19/13)

There has been a lot of discussion about mental health and gun control since the tragic shootings in Newtown, Conn. The public longs for a mental health system that produces clear warning signs that a person has a propensity to be violent. New York State legislators passed a gun bill that would require therapists to report to the authorities any client thought to be "likely to engage in" violent behavior. Under the law, the police would confiscate any weapons the person had. Some advocates favor the reporting provision as having the potential to prevent a massacre yet many patient advocates and therapists strongly disagree, saying it would intrude into the doctor-patient relationship in a way that would dissuade troubled people from telling their therapists their intent. Under current ethical guidelines, only involuntary hospitalizations and direct threats made by patients are reported to authorities.

Dr. Paul Appelbaum, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, is concerned that looking for "warning signs" is more art than science. People with serious mental disorders, while more likely to commit aggressive acts than the average person, account for only about 4% of violent crimes overall.

The sort of young, troubled males who seem to psychiatrists most likely to commit school shootings - identified because they have made credible threats - often do not qualify for any diagnosis. They might have elements of paranoia or deep resentment or of narcissism, a grandiose self-regard that are noticeable, but do not add up to any specific "disorder" according to strict criteria. ("Warning Signs of Violent Acts Often Unclear", Benedict Carey and Anemona Hartocollis, New York Times, 1/16/13).

Dr. Deborah Weisbrot, director of the outpatient clinic of child and adolescent psychiatry at Stony Brook University, who has interviewed about 200 young people, mostly teenage boys, who have made threats, says, "What they have in common is a kind of magical thinking, odd beliefs like they can read other people's minds, or see the future or that things happening in their dreams come true."

What mainly comes out of the Newtown, Connecticut school shooting, is the opportunity that only comes once every generation or two: to rethink the entire mental health system, to expand community mental health care, focus more on young people, and reduce stigma. "It seems to me an opportunity to step back and rethink what the entire system should look like", says Dr. Appelbaum. ("Warning Signs of Violent Acts Often Unclear", Benedict Carey and Anemona Hartocollis, New York Times, 1/16/13).

President Obama has called for a national dialogue on mental health to address the culture of silence and negative perceptions of mental illness that prevents our citizens from receiving the treatment they deserve. Mental health conditions place a greater burden on our economy than cancer or heart disease; and yet more than 60% of people with mental illness do not receive help. Why is this? Partially because of the stigma attached to mental illness. People are afraid to seek help because of the way mentally ill people are treated in the media and by others who are ignorant. Tens of millions of Americans with mental health conditions that are treated are living healthy lives and contributing to their communities. Now is the time to work together to focus on affordable treatment for those who are not receiving treatment and to bring mental health out of the shadows in which it has been imprisoned.

www.maureenmurdock.com

To Watch TV or Not

Long lockdowns, and the lack of programs and activities for prisoners, have steered even the most prolific readers to watch TV. But, after hours of reading, I feel productive, like I have planted some seeds, while after hours of television, I feel wasted, as if I have no spirit or life inside, as if I have wasted time I don't have to lose.

I must admit I like watching sports, nature, Discovery, some PBS, and not-made-in-USA shows. Also some cooking programs if I have real food to eat myself. But even PBS has turned bland and succumbed to some government and big-business pressure.

The shows nowadays on so called "free TV" are 99 percent garbage, especially network shows, news, and talk show programs. Reality shows with no reality. The programs worth watching - like Discovery, Animal Planet, National Geographic, Nova, art and live sports - have all been moved to cable or satellite, and are hidden from our view. We are left with the dumbest dumbed down reality shows and the most unrealistic cop shows that indoctrinate their audiences with false justice and false rights of criminals where poor people receive good and real lawyers and all the judges and law enforcement officials are angels, heroes, and good people, people who have never spat on the sidewalk and are only down here from heaven to make sure poor people and people of color get justice.

All the stuff you see in law enforcement shows is only true for TV. More often than not, people of color and the poor are not getting good lawyers or real justice. No judge or prosecutors care about an accused receiving healthy court representation. That's a myth, as is the one about justice being color-blind in the USA which has always been a myth.

TV was not allowed into prisons in California until the late 1970s when the Department of Corrections figured out that TV could dumb down and pacify the masses of prisoners through lifeless, vicarious living. Even the prison videos they show are mainly violent with no redeeming value.

I remember when I came to prison in the late '70s that TV still had not become like crazy glue. TV was still not yet paramount in prisoners' lives; had not totally paralyzed and chilled the minds, hearts, and soul; and had not turned off our ability to learn, grow, and come together to promote deeper and higher education, positive change, and civil and human rights.

Now the first thing one does in the morning is turn on the TV, like a drink of water. I don't think TV can be a learning tool because it lulls and forces the mind and imagination to sleep and makes the creative spirit lazy.

Knowledge, heart, wisdom, and change used to bounce off, through and beyond these walls, when prison was a positive change universally recognized around the world for imparting positive conscious-raising and awareness that lifted prisoners' spirits and hope and which acted as a catalyst for positive social change regarding human rights and the rights of the poor.

When I turn the TV off, time flows better and minutes and hours become enriched and enlightened. This morning, before I knew it, I had read seventy pages of a new book. Suddenly, it was dinner time and my mind, heart, and spirit were busy pondering ideas beyond prisons of any kind.

Spoon Jackson B-92377

CSP-Sac Box 290066

Represa, CA 95671-0066

blog: realnessnetwork.blogspot.com

SJRA Advocate is happy to celebrate its 4th anniversary with this issue. Thanks to all our supporters!

-Advertisement-

Prisoner Rights Attorney

Charles Carbone, Esq.

"Every case I take is given compassionate, thorough and vigorous representation with one goal in mind - Justice for the Incarcerated."

- Charles Carbone

Personally and professionally dedicated to fighting for prisoner rights and human rights for California prisoners and their families.

Charles represents prisoners in California's worst prisons on conditions of their confinement, including (but not limited to):

* Parole Lifer Hearings

* En banc & Rescission Lifer Hearings

* State & Federal Appeals of Parole Denials

* State & Federal Appeals of Criminal Convictions

* Indeterminate Gang Validations for SHU Prisoners

* Appeals of CDC 115s

15 years of experience in prison law (California cases ONLY)

PO Box 2809

San Francisco, CA 94126

(415) 981-9773

www.prisonerattorney.com

For life inmate subscriptions to Quarterly Parole Matters Newsletter

Please send $15/year for inmates or $25/year for family members

LIFE IN LIMBO:

An Examination of Parole Release for Prisoners Serving Life Sentences with the Possibility of Parole in California

Robert Weisberg, Debbie A. Mukamal and Jordan D. Segall

September 2011

Stanford Criminal Justice Center

Stanford Law School

559 Nathan Abbott Way

Stanford, CA 94305

www.law.stanford.edu/program/centers/scjc

Continuing from Jan-Feb issue on "Inmate Characteristics"

Pages 23-24 of the report

INMATE CHARACTERISTICS (Cont'd)

Behavior in Prison

Inmate behavior during the prison term is a recurring theme in parole hearings. Parole commissioners typically scrutinize inmate's disciplinary records, and often ask detailed questions about violations of prison rules.

In California prisons, disciplinary infractions are documented using two forms, the CDC 128 "Custodial Counseling Chrono" (or sometimes the CDC 128B "Informational Chrono"), and the CDC 115 "Rules Violation Report". 128 infractions are typically minor conduct violations, including smoking, being in an unauthorized area, using foul language, or possessing non-serious contraband. 115 infractions, which trigger a notice-and-hearing process, can be either non-serious ("administrative") or serious. Serious violations include violence toward inmates or prison personnel, possession of controlled substances or weapons, and other serious infractions.

Both 115s and 128s are exceedingly common. Eighty-one percent of inmates in our sample have at least one 115 in their record, and 89 percent of inmates have at least one 128. The 115 infractions are strongly associated with the grant rate; 25 percent of inmates with no 115 infractions received parole grants, while only 13 percent of inmates with at least one 115 infraction received a grant - a result significant at the .01 level. And the more 115s an inmate accumulates, the greater an effect the inmate's disciplinary record has on the inmate's chances for parole release. Just 16 of the 149 inmates with more than five 115s (11 percent) received parole release. On the other hand, 128 infractions are not significantly associated with grant rate. One inmate received a grant of parole despite accumulating sixty 128 infractions.

Preliminary evidence also suggests that the seriousness of the disciplinary violation has a substantial effect on commissioners' decisions. For example, violent disciplinary infractions, regardless of when they occur, are significantly associated with parole denials. Only 11 of the 128 (8.5 percent) inmates with violent disciplinary records in prison were released, compared to 20 percent of inmates with no violent disciplinary infractions.

Psychological Evaluations

Virtually all inmates who appear at parole hearings have undergone psychological evaluations. Parole commissioners always receive and often review the results of these evaluations carefully.

The two most common types of clinical opinions in our sample are the Axis V Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and the Clinician Generic Risk assessment. 52 The Axis V GAF measures a patient's overall level of psychological, social, and occupational functioning on a 100-point continuum, with higher scores indicating higher functioning. The Clinician Generic Risk, by contrast, assigns inmates a simple risk-of-recidivating score: low, low-moderate, moderate, moderate-high, and high.

Both the Clinician Generic Risk and the Axis V-GAF are significantly correlated with grant rate. This is especially true of the Clinician Generic Risk assessment, which is statistically significant at the .001 level. As Chart 18 indicates, inmates who receive an average score or higher virtually never receive parole release. Similarly, none of the inmates in our sample who received below 75 on the Axis V-GAF enjoyed favorable release outcomes.

These results suggest that the psychological evaluation tools used to assess risk potential and inmate psychological stability play an influential role in the parole process.

[Chart 18: Grant Rate by psychological Evaluation Instrument]

Drug Abuse

During parole hearings, commissioners often discuss inmates' records of drug and alcohol abuse at considerable length. A history of drug or alcohol abuse is not correlated with grant rate. What is highly associated with grant rate, however, is whether an inmate is participating in a "twelve-steps" program (that is, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, or some similar program), and whether he or she can correctly answer questions about those steps, which commissioners often ask to test inmates' commitment to drug and alcohol treatment.

Conclusion

The foregoing analyses are necessarily preliminary, but they shed important light on how the parole hearing process functions in California. Some results, like the importance of in-prison conduct and psychological evaluations, confirm standard presuppositions about what matters to parole commissioners. Other results, like the irrelevance of age and offense type, are counterintuitive.

As the study proceeds, we will continue to analyze factors that contribute to parole release decisions, with the goal of developing a comprehensive model of parole decisionmaking in California.

Next issue, "Further Empirical Research on the Parole Release Process for Lifers" and Endnotes on this "Life in Limbo" report.

Court Ruling Provides an Opportunity for Real Change, Advocates push for measures to reduce prison population

For Immediate Release - April 12th, 2013

Contact: Emily Harris, Californians United for a Responsible Budget

510-435-1176

Sacramento: Yesterday's ultimatum by the 3-Judge panel puts Gov. Brown and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) on notice to present a plan for further reductions in the state's unconstitutionally crowded prisons within the next three weeks.

"The propaganda that Gov. Brown & Secretary Beard have been feeding Californians didn't cut the mustard with the Court", said Misty Rojo, Program Coordinator for the California Coalition for Women Prisoners. "Conditions inside continue to be terrible, and in women's prisons the situation is getting worse."

Advocates who have criticized the Governor's criminal justice realignment plan as inadequate were quick to praise the Court decision.

"Realignment itself, no matter how it was implemented, was never going to produce an adequate reduction in the prison population", said Diana Zuniga, Field Organizer for Californians United for a Responsible Budget. "It has been clear for years that a serious solution to the prison crisis would require serious sentencing reforms and changes to parole and compassionate release policies."

The Court ordered the CDCR and Governor to "identify prisoners unlikely to reoffend" and reduce the population by 9,000 before the end of the year. The Court threatened the Governor and other state officials with contempt of court if they fail to comply. Groups led by those who are members of Californians United for a Responsible Budget have worked for years to convince Sacramento to institute common sense changes already in place successfully in other states, including:

* Expand Medical Parole/Discharge Prisoners who are permanently medically incapacitated

* Use Compassionate Release for the terminally ill

* Create Parole eligibility for elderly prisoners

* Expand use of the Alternative Custody Program

* Parole eligible term-to-life prisoners

* Reform drug sentencing laws

* Restore conduct credits for those in SHU and expand credits for others.

"This is a historic opportunity for the Governor", said Debbie Reyes of the California Prison Moratorium Project. "Governor Brown put California on the disastrous road to mass incarceration during his second term in the 1980s. During his second, second term, he can begin the process of turning California away from a prison-first mindset. The sorts of real changes the Court demands will require changes to California's dysfunctional sentencing laws. Those changes should, as the Court suggest, be applied both prospectively and retrospectively."

"Will Gov Brown and Secretary Beard continue to dig in their heels to defend an indefensible prison system? Or will they demonstrate that they have the courage, vision and leadership we need to make meaningful changes to our super-sized prison system?" asked Zuniga.

Prison Blues Art

By Larry James D. Russell

3-26-13

Child 1: Mr. Governor, I think it's time to just comply with the court's order and stop squandering tax payers' money!

Governor: Look kid, I don't care what you think. Besides, by the time you are 18 you'll be in prison because you live in California!

Child 2: You suck!

Child 3: You suck! You lost!

Child 4: Yeah, poor loser!

PoliticsBlog from the San Francisco Chronicle, posted by Bob Egelko, Apr 18, 5:27pm

"Brown and other state officials have engaged in openly contemptuous conduct, the court said in last week's ruling, by repeatedly ignoring both this court's order and at least three explicit admonitions to take all steps necessary to comply with that order. All they have submitted so far, the judges said, is a plan for non-compliance. And if they don't start complying, starting with the population-reduction plan due by the start of next month, they will without further delay be subject to findings of contempt, individually and collectively."

Other posts by this author

|

2025 apr 13

|

2024 dec 10

|

2024 nov 10

|

2024 aug 21

|

2024 jun 25

|

2024 jun 10

|

More... |

Replies