Transcription

PRISON

POLICY INITIATIVE

BERNADETTE RABUY

Policy & Communications Associate

main: (413) 527-0845

email: brabuy@prisonpolicy.org

twitter: @PrisonPolicy

PO Box 127

Northampton Mass 01061

www.prisonpolicy.org

www.prisonersofthecenuss.org

December 17, 2015

Dear Kenyl,

Thank you for your letters. Here is The Boston Globe address:

Mailing Address:

P.O. Box 55819 Boston, MA 02203-5819

I am also attaching our most recent report, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2015, and a recent The New York Times editorial featuring another one of our recent reports, States of Women's Incarceration: The Global Context. Unfortunately, we don't have a paper version of that report.

Happy Holidays to you!

Sincerely,

[signature blanked out]

Bernadette Rabuy

Policy & Communications Associate

A22 THE NEW YORK TIMES EDITORIALS/LETTERS MONDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2015

The New York Times

ARTHUR OCHS SULZBERGER JR., Publisher, Chairman

Founded in 1851

ADOLPH S. OCHS

Publisher 1896-1935

ARTHUR HAYS SULZBERGER

Publisher 1935-1961

ORVIL E. DRYFOOS

Publisher 1961-1963

ARTHUR OCHS SULZBERGER

Publisher 1962-1992

Women Behind Bars

In the last few years, America's out-of-control incarceration boom has finally started to get the sustained public scrutiny, and condemnation, that it deserves. But one key element of the story still receives too little attention: the number of women in the nation's prisons and jails.

Men account for more than 90 percent of those behind bars. But the number of female inmates, most of whom are mothers, has been growing at an even faster rate than the overall prison population. In 1980 there were just over 15,000 women in state prisons. By 2010 there were nearly 113,000. When jail inmates are added in, there are about 206,000 women currently serving time - nearly one-third of all female prisoners in the world.

This soaring population is largely a result of the war on drugs; the vast majority of the women behind bars were convicted of low-level drug or property crimes, rather than violent crimes. Many of them were swept up in larger conspiracy prosecutions targeted primarily at drug dealers they were living with. Many suffer from mental illness or drug addiction. And as is true with men, the racial disparities are severe: Black women are locked up at almost three times the rate of white women.

A new report by the Prison Policy Initiative quantifies just how extreme an outlier the United States is. Thailand is the only country with a higher incarceration rate for women that the United States over all. But individual states are far worse. West Virginia has the highest rate in the world, imprisoning 273 of every 100,000 women, with nearly two dozen other states not far behind.

The burdens of incarceration to women are particularly heavy. A large percentage of female prisoners have experienced physical and sexual abuse in their lives. One 1996 study of California prisoners found that 92 percent of women in prison had been abused, and often that abuse continues inside prison walls by male guards.

Pregnant women face their own gantlet of humiliation behind bars. In 28 states, women may be shackled during labor and delivery, and while caring for their newborns - a "barbaric" practice that continues despite the lack of any evidence that they pose a threat. Most of the newborns are immediately separated from their mothers after birth.

And then there is the destructive impact on families. Two-thirds of women entering prison have children. If those children are lucky, they get placed with their grandparents or other stable, long-term caregivers. But many are shipped off to foster homes and bounced for years among temporary housing situations, which only makes their path to a successful adulthood more difficult.

The cost of imprisonment for nonviolent crimes has severely burdened state and federal budgets, with little demonstrated benefit to public safety. As the nation struggles with how to shrink its overcrowded prisons and jails, low-level and nonviolent offenders are often among the first considered for release.

A majority of female prisoners fall into this category, and because their imprisonment so often has such a direct and negative impact on their families, they should be at the top of the list.

PRISON

POLICY INITIATIVE

Mass Incarceration:

The Whole Pie 2015

By Peter Wagner and Bernadette Rabuy

December 8, 2015

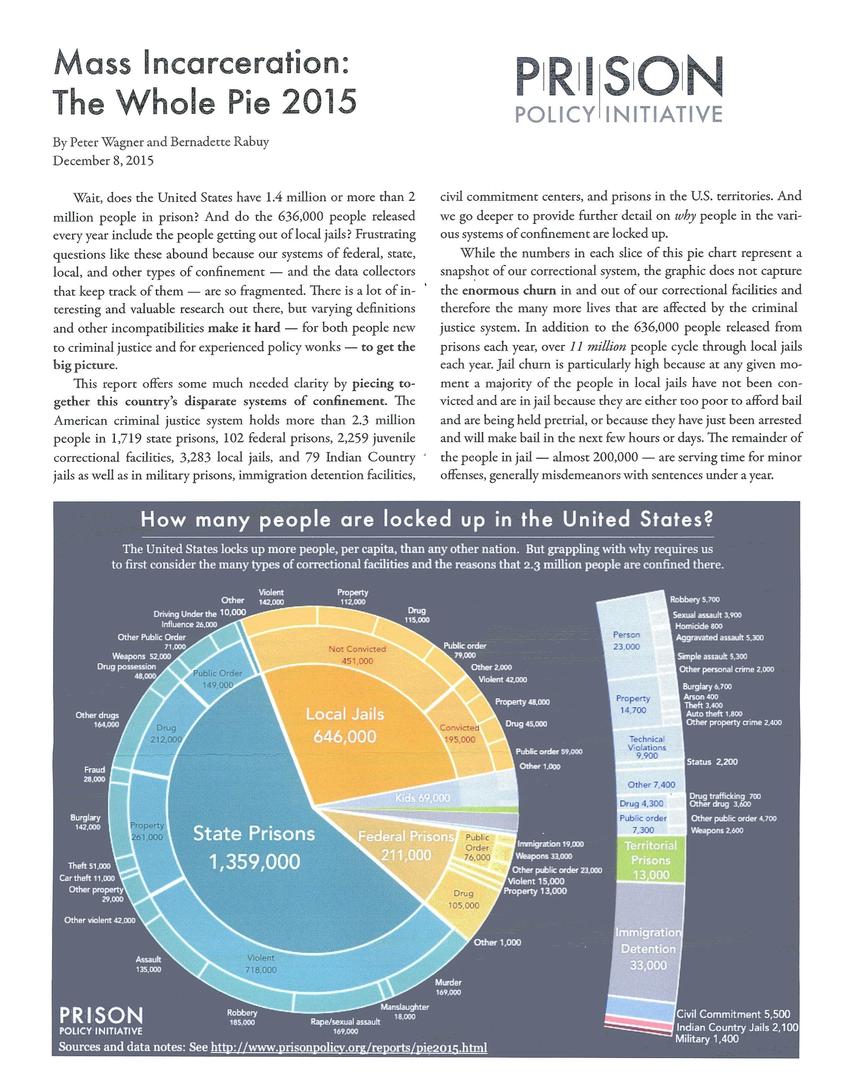

Wait, does the United States have 1.4 million or more than 2 million in people in prison? And do the 636,000 people released every year include the people getting out of local jails? Frustrating questions like these abound because our systems of federal, state, local, and other types of confinement - and the date collectors that keep track of them - are so fragmented. There is a lot of interesting and valuable research out there, but varying definitions and other incompatibilities make it hard - for both people new to criminal justice and for experienced policy wonks - to get the big picture.

This report offers some much needed clarity by piecing together this country's disparate systems of confinement. The American criminal justice system holds more than 2.3 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 2,259 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,283 local jails and 79 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, and prisons in the U.S. territories. And we go deeper to provide further detail on why people in the various systems of confinement are locked up.

While the numbers in each slice of this pie chart represent a snapshot of our correctional system, the graphic does not capture the enormous churn in and out of our correctional facilities and therefore the many more lives that are affected by the criminal justice system. In addition to the 636,000 people released from prisons each year, over 11 million people cycle through local jails each year. Jail churn is particularly high because at any given moment a majority of the people in local jails have not been convicted and are in jail because they are either too poor to afford bail and are being held pretrial, or because they have just been arrested and will make bail in the next few hours or days. The remainder of the people in jail - almost 200,000 - are serving time for minor offenses, generally misdemeanors with sentences under a year.

How many people are locked up in the United States?

The United States locks up more people, per capita, than any other nation. But grappling with why requires us to first consider the many types of correctional facilities and the reasons that 2.3 million people are confined there.

[pie chart showing:

- 1,359,000 prisoners in State Prisons; of which 718,000 of these for violent crimes including 169,000 for murder, 18,000 for manslaughter, 169,000 for rape/sexual assault, 185,000 for robbery, 135,000 for assault and 42,000 for other violent crimes; 261,000 for property crimes including 28,000 for fraud, 142,000 for burglary, 51,000 for theft, 11,000 for car theft and 29,000 for other property crimes; 212,000 for drug crimes including 48,000 for drug possession and 164,000 for other drug crimes; 149,000 for public order crimes including 52,000 for weapons, 26,000 for driving under the influence and 71,000 for other public order crimes; and 10,000 for other crimes.

- 646,000 prisoners in Local Jails; of which 451,000 are not convicted for crimes including 142,000 for violent crimes, 112,000 for property crimes, 115,000 for drug crimes, 79,000 for public order crimes and 2,000 for other crimes; 195,000 are convicted for crimes including 42,000 for violent crimes, 48,000 for property crimes, 45,000 for drug crimes, 59,000 for public order crimes and 1,000 for other crimes.

- 211,000 prisoners in Federal Prisons; of which 105,000 are for drug crimes; 13,000 for property crimes; 15,000 for violent crimes; 76,000 for public order crimes including 19,000 for immigration, 33,000 for weapons and 23,000 for other public order offenses; and 1,000 for other crimes.

- 69,000 Kids; of which 23,000 for personal crimes including 5,700 for robbery, 3,900 for sexual assault, 800 for homicide, 5,200 for aggravated assault, 5,300 for simple assault and 2,000 for other personal crime; 14,700 for property crimes including 6,700 for burglary, 400 for arson, 3,400 for theft, 1,800 for auto theft and 2,400 for other property crime; 9,900 for technical violations; 2,200 for status crimes; 4,300 for drug crimes including 700 for drug trafficking and 3,600 other drug crimes; 7,300 for public order crimes including 2,600 for weapons and 4,700 for other public order crimes; and 7,400 for all other crimes.

- 13,000 prisoners in Territorial Prisons

- 33,000 prisoners in Immigration Detention

- 5,500 prisoners in Civil Commitment

- 2,100 prisoners in Indian Country Jails

- 1,400 prisoners in Military prisons]

PRISON

POLICY INITIATIVE

Sources and data notes: See http://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2015.html

With a sense of the big picture, a natural follow-up question might be: how many people are locked up for a drug offense? While the data doesn't give us a complete answer, we know that almost half a million adults and children are locked up because their most significant offense was a drug offense. The data confirms that non-violent drug convictions are a defining characteristic of the federal prison system, but play only a supporting role at the state and local levels. Critically, while drugs are the most significant offense for only a minority of people in state and local facilities, there are 1.6 million drug arrests each year, giving residents of over-policed communities criminal records, which then serve to increase sentences imposed for any future offenders and have many other damaging effects.

All of this offense data comes with an important set of caveats. A person in prison for multiple offenses is reported only for the most serious offense, so, for example, there are people in prison for "violent" offenses whose time in prison is extended by the fact that they were also convicted for a drug offense. Further, almost all convictions are the result of plea bargains, where people plead guilty to a lesser offense - an offense perhaps of a different category or one that they may not have actually committed. And many of these categories are nowhere near as clear as the labels imply. For example, "murder" is generally considered to be an extremely serious offense, but that broad category groups together the rare group of serial killers, with people who committed acts that are unlikely for reasons of circumstances or advanced age to ever happen again, with offenses that the average American would not consider to be murder at all. For example, the felony murder rule says that if someone dies during the commission of a felony, everyone involved is as guilty of murder as the person who pulled the trigger. Driving a getaway car during a bank robbery where someone was accidently killed is indeed a serious offense, but few people would really consider that to be murder.

This "whole pie" methodology also exposes some disturbing facts about the youth entrapped in our juvenile justice system: Too many are there for a "most serious offense" that is not even a crime. For example, there are almost 10,000 children behind bars for "technical violations" of the requirements of their probation or parole, rather than for a new offense. Further, more than 2,000 children are behind bars for "status" offenses, which are, as the U.S. Department of Justice explains: "behaviors that are not law violations for adults, such as running away, truancy, and incorrigibility."

Turning finally to the people who are locked up because of immigration-related issues, we find that 19,000 people are in federal prison for criminal convictions of violating federal immigration laws. A separate 33,000 are civilly detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) separate from any criminal proceedings and are physically confined in special immigration detention facilities or in one of the many hundreds of local jails under contract with ICE. (Notably, these categories do not include the people represented in other pie slices who are also in some early state of the deportation process because of non-immigration related criminal convictions.)

Now, armed with the big picture of how many people are locked up in the United States in the various types of facilities and for what offenses, we have a better foundation for the long overdue conversation about criminal justice reform. For example, the data makes it clear that ending the War on Drugs will not alone end mass incarceration, and it demonstrates why the policymakers and advocates who see ending the War on Drugs as a politically acceptable first step towards ending mass incarceration must take great care that their actions both constitute actual progress for people with drug offenses and do not make further reforms more difficult. Looking at the "whole pie" also opens up other conversations about where we should focus our energies:

- What is the role of the federal government in ending mass incarceration? The federal prison system is just a small slice of the total pie, but the federal government can certainly use its financial and ideological power to incentivize and illuminate better paths forward.

- Are state officials and prosecutors willing to rethink both the War on Drugs and the reflexive policies that have served to increase both the odds of incarceration and length of stay for "violent" offenses?

- Do policymakers and the public have the focus to also confront the geographically and politically dispersed second largest slice of the pie: the 3,283 local jails? Given that the people behind bars in this country are disproportionately poor and shut out of the economy, does it make sense to lock up millions of people for a few days at a time for minor offenses? Will our leaders be brave enough to ask the public to support smarter investments in community-based drug treatment and job training? Or will they support the continued use of jails as mass incarceration's front door?

And once we have wrapped our minds around the "whole pie" of mass incarceration, we should zoom out and note that being locked up is just one piece of the larger pie of correctional control. There are another 850,000 people on parole (a type of conditional release from prison) and a staggering - and growing - 3.9 million people on probation (what is typically an alternative sentence). Particularly given the often onerous conditions of probation, policymakers should be cautious of "alternatives to incarceration" that serve to widen the net of punishment to people who previously would not have been subject to punishment in the first place.

All correctional control

[pie chart showing Probation 55%, the pie chart above 33% and parole 12%]

Now that we can see the big picture of how many people are locked up in the United States in the various types of facilities, we can see that something needs to change. Looking at the big picture requires us to ask if it really makes sense to lock up 2.3 million people on any given day, giving this nation the dubious distinction of having the highest incarceration rate in the world. Both policymakers and the public have the responsibility to carefully consider each individual slice in turn to ask whether legitimate social goals are served by putting each category behind bars, and whether any benefit really outweighs the social and fiscal costs.

We're optimistic that this "whole pie" approach can give Americans, who are ready for a fresh look at the criminal justice system, some of the tools they need to demand meaningful changes to how we do justice.

For the footnotes and data sources to this report, see

prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2015.html

To join our newsletter and receive more cutting edge research and advocacy, go to prisonpolicy.org/subscribe/

Other posts by this author

|

2016 aug 2

|

2016 mar 20

|

2016 mar 3

|

2016 mar 3

|

2015 nov 15

|

2015 nov 15

|

More... |

Replies