Transcription

https://www.splcenter.org/news/2018/06/13/alabama-prison-system-sees-steep-rise-suicides

SPLC

Southern Poverty

Law Center

Alabama prison system sees

steep rise in suicides

June 13, 2018

The SPLC argued in federal court today that Alabama's mistreatment of prisoners with mental illness has led to a dramatic increase in suicides.

Since the beginning of 2018, four people in ADOC custody - three in solitary confinement and one on death row - have died by suicide. The suicide rate in Alabama prisons is one of the highest in the country.

In June 2017, U.S. District Judge Myron H. Thompson declared the mental health system in Alabama prisons "horrendous masquerade" an unconstitutional failure that led to what Thompson called a "skyrocketing suicide rate" among prisoners.

Thompson's ruling followed a two-month trial in the SPLC's lawsuit against the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC). Today's hearing was about ADOC's routine use of segregation - solitary confinement - for prisoners with mental illness.

"As far as we can tell, the state has done very little beyond promising to improve conditions in Alabama prisons," said Maria Morris, senior supervising attorney for the SPLC. "We continue to see the mentally ill kept in extreme isolation, and this is driving a steep rise in suicides.

"Even more disturbing, the suicide rate has dramatically increased since we filed this lawsuit in 2014. ADOC has been ordered to increase mental health and correctional officer staffing, and, hopefully, will do so over the coming years. However, the level of correctional staffing has fallen significantly since the start of the lawsuit. Last summer, as the situation become increasingly dire, the state stopped publicly reporting its staffing levels. ADOC has refused to provide information about its mental health staffing levels, but the information we've received suggests that it has fallen this year.

"It's sickening to witness people - many of whom have mental illnesses - endure so much suffering while the state stalls and makes excuses. Incredibly, at the same time more people under its care are taking their lives, ADOC is asking the court and the people of this state to trust it to provide the care the U.S. Constitution requires.

"For well over a year, ADOC has ignored the urgent need to protect people with serious mental illnesses from the detrimental effects of extreme isolation. Segregation can be deadly, especially for those who are already struggling, and the recent rise in prison suicides highlights this tragic reality."

In 2016, the plaintiffs settled the first phase of the lawsuit regarding violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act. In that settlement, ADOC committed to providing services and fair treatment to incarcerated people with disabilities.

The third phase of the lawsuit will determine whether the prison system's poor medical and dental services violate the Eighth Amendment's ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Trial dates for those claims have not been set.

The Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program and the law firms Baker Donelson, and Zarzaur Mujumdar & Debrosse filed the lawsuit in conjunction with the SPLC.

***

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/commissary.html

The Company Store:

A Deeper Look at Prison Commissaries

By Stephen Raher

May 2018

Press release

Prison commissaries are an essential but unexamined part of prison life. Serving as the core of the prison retail market, commissaries present yet another opportunity for prisons to shift the costs of incarceration to incarcerated people and their families, often enriching private companies in the process. In some contexts, the financial exploitation of incarcerated people is obvious, evidenced by the outrageous prices charged for simple services like phone calls and email. When it comes to prison commissaries, however, the prices themselves are not the problem so much as forcing incarcerated people - and by extension, their families - to pay for basic necessities.

Understanding commissary systems can be daunting. Prisons are unusual retail settings, date are hard to find, and it's hard to say how commissaries "should" ideally operate. As the prison retail landscape expands to include digital services like messaging and games, it becomes even more difficult and more important for policymakers and advocates to evaluate the pricing, offerings, and management of prison commissary systems.

The current study

To bring some clarity to this bread-and-butter issue for incarcerated people, we analysed commissary sales reports from state prison systems in Illinois, Massachusetts, and Washington. We chose these states because we were able to easily obtain commissary data, but conveniently, these three states also represent a decent cross section of prison systems, encompassing a variety of sizes and different types of commissary management.1

We found that incarcerated people in these states spent more on commissary than our previous research suggested, and most of that money goes to food and hygiene products. We also discovered that even in state-operated commissary systems, private commissary contractors are positioned to profit, blurring the line between state and private control.

Lastly, commissary prices represent a significant financial burden for people in prison, even when they are comparable to those found in the "free world." Yet despite charging seemingly "reasonable" prices, prison retailers are able to remain profitable, which raises serious concerns about new digital products sold at prices far in excess of market rates.

How much do incarcerated people spend in the commissary?

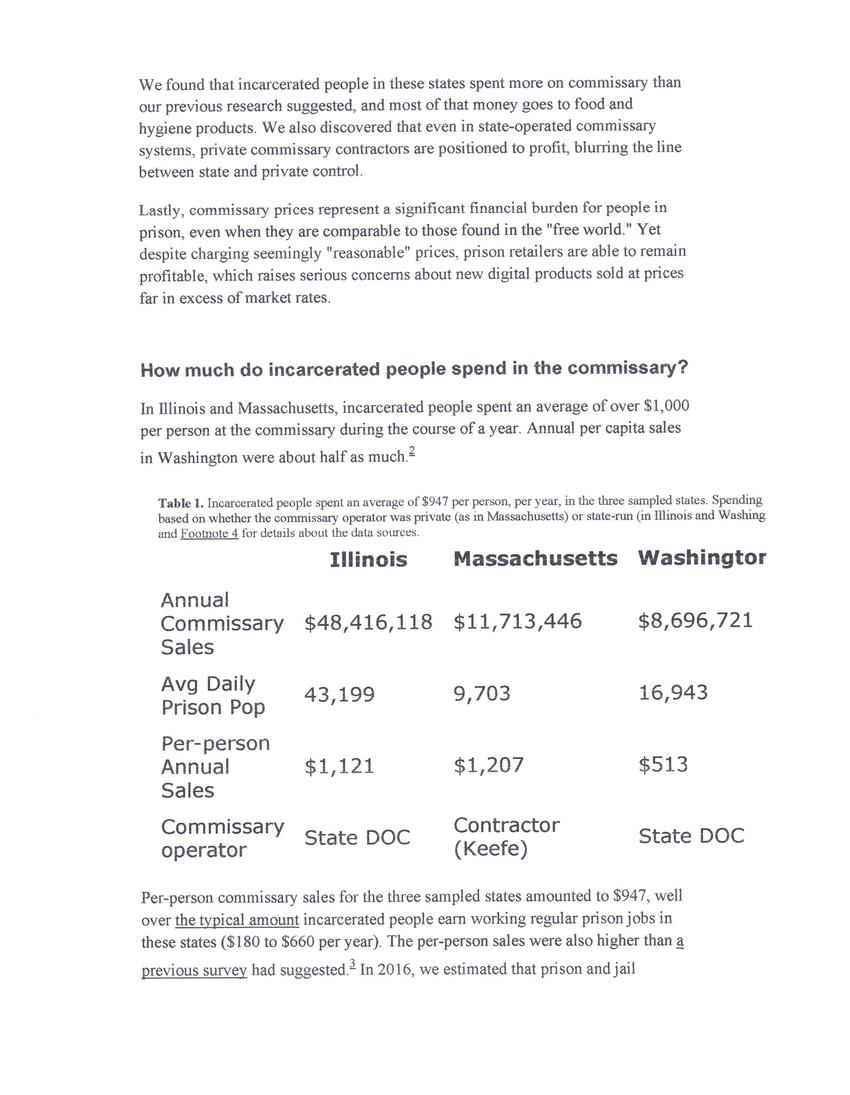

In Illinois and Massachusetts, incarcerated people spent an average of over $1,000 per person at the commissary during the course of a year. Annual per capita sales in Washington were about half as much.2

Table 1. Incarcerated people spent an average of $947 per person, per year, in the three sampled states. Spending based on whether the commissary operator was private (as in Massachusetts) or state-run (in Illinois and Washington and Footnote 4 for details about the data sources.

Annual Commissary Sales

Illinois - $48,416,118

Massachusetts - $11,713,446

Washington - $8,696,721

Avg Daily Prison Pop

Illinois - 43,199

Massachusetts - 9,703

Washington - 16,943

Per-person Annual Sales

Illinois - $1,121

Massachusetts - $1,207

Washington - $513

Commissary operator

Illinois - State DOC

Massachusetts - Contractor (Keefe)

Washington - State DOC

Per-person commissary sales for the three sampled states amounted to $947, well over the typical amount incarcerated people earn working regular prison jobs in these states ($180 to $660 per year). The per-person sales were also higher than a previous survey had suggested.3 In 2016, we estimated that prison and jail commissary sales amount to $1.6 billion per year nationwide, based in part on date from a 34-state survey by the Association of State Correctional Administrators. But the more recent and more detailed date presented in this report suggest that commissary might be an even higher-grossing industry that we previously thought.

There were important state differences in commissary sales, however. Washington's per-person average was dramatically lower than the other two states'. The reason for this difference isn't entirely clear, but it seems that personal property policies issued by the Department of Corrections are at least partially responsible for this significant disparity.

What are people buying?

Annual per-person sales average only tell part of the story. We also wanted to look closely at what people were spending their money on. To do this, we obtained detailed inventory reports from the three commissary systems and categorized (when possible) each inventory item and its commensurate sales figures.4

Annual prison commissary sales in Illinois, per person

Annual prison commissary sales in Washington, per person

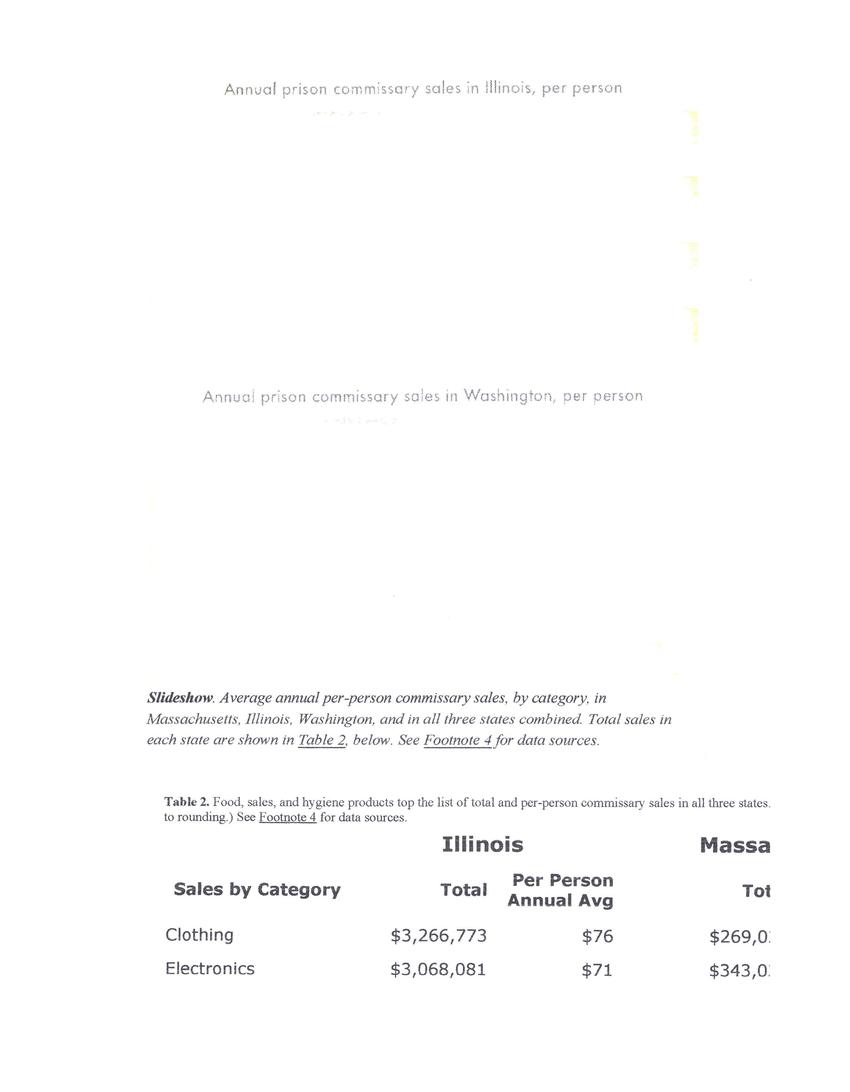

Slideshow. Average annual per-person commissary sales, by category, in Massachusetts, Illinois, Washington, and in all three states combined. Total sales in each state are shown in Table 2, below. See Footnote 4 for data sources.

Table 2. Food, sales, and hygiene products top the list of total and per-person commissary sales in all three states, to rounding.) See Footnote 4 for data sources.

Not surprisingly, food dominates the sales reports; prison and jail cafeterias are notorious for serving small portions of unappealing food. Another leading problem with prison food is inadequate nutritional content. While the commissary may help supplement a lack of calories in the cafeteria (for a price, of course), it does not compensate for poor quality. No fresh food is available, and most commissary food items are heavily processed. Snacks and ready-to-eat food are major sellers, which is unsurprising given that many people need more food than the prison provides, and the easiest — if not only — alternatives are ramen and candy bars.

It's a myth that incarcerated people are buying luxuries; rather, most of the little money they have is spent on basic necessities.

These data contradict the myth that incarcerated people are buying luxuries; rather, most of the little money they have is spent on basic necessities. Consider: If your only bathing option is a shared shower area, aren’t shower sandals a necessity? Is using more than one roll of toilet paper a week really a luxury (especially during periods of intestinal distress)? Or what if you have a chronic medical condition that requires ongoing use of over-the-counter remedies (e.g., antacid tablets, vitamins, hemorrhoid ointment, antihistamine, or eye drops)? All of these items are typically only available in the commissary, and only for those who can afford to pay.

Bringing this discussion into the realm of the concrete, consider the following examples from Massachusetts. In FY 2016, people in Massachusetts prisons purchased over 245,000 bars of soap, at a total cost of $215,057. That means individuals paid an average of $22 each for soap that year, even though DOC policy supposedly entitles them to one free bar of soap per week. Or to take a different example: the commissary sold 139 tubes of antifungal cream. Accounting for gross revenue of just $556, the commissary contractor is obviously not getting rich selling antifungal cream, no matter the mark-up—instead, the point is that it’s hard to imagine why anyone would purchase antifungal cream other than to treat a medical condition. Yet Massachusetts has forced individual commissary customers to pay for their own treatment, at $4 per tube, which can represent four days’ wages for an incarcerated worker.

How do incarcerated people afford commissary?

Policies drive consumption: property ownership and prison pay rates

(expand)

For many people in prison, their meager earnings go right back to the prison commissary, not unlike the sharecroppers and coal miners who were forced to use the “company store.” When their wages are not enough, they must rely on family members to transfer money to their accounts — meaning that families are effectively forced to subsidize the prison system. Others in prison who lack such support systems simply can’t afford the commissary at all.

While the sales data allow us to calculate average commissary expenditures per person using the total prison population, this number does not tell the whole story: It flattens the spending gap between prisoners who can “afford” to buy from the commissary versus those who cannot.

The poorest people in prison, such as those considered “indigent” by the state, spend little to nothing at the commissary. This, in turn, means that the per capita spending for all others is actually greater than the average numbers reported above. We can get a very limited glimpse of this population by looking at Washington, where commissaries stock certain items that are available only to people who qualify as indigent. Based on annual sales of “indigent toothpaste” and “indigent soap,” it appears that a significant portion of people in Washington’s prisons (between about ten percent and one-third) are indigent.

How “fair” are free-world prices in a prison?

Illustration showing that incarcerated people may have to work for 13 hours to afford dental flossIllustration by Elydah Joyce

One rather surprising finding is that prices for some common items were lower than prices found at traditional free-world retailers. Other commissary prices were higher, but only by a little bit. (See Table 3.)

This isn’t to say that prison commissaries are in the business of providing bargains. Rather, it is a natural result flowing from the fact that a regular retailer has substantial costs (such as operating a network of retail outlets and advertising) that don’t arise in the prison context. In fact, a prison commissary is somewhat analogous to an online retailer like Amazon: goods move directly from a warehouse to the customer, without the expenses associated with maintaining a traditional retail presence. In addition, commissary operators have a legal monopoly, so they don’t have to worry about price competition, and thus do not incur costs associated with special sales or discounts.

Table 3. While prices for some items are comparable or even lower than prices found in free-world stores, the costs are significant for incarcerated people and their families. (Note that in Illinois, commissary prices vary by facility, so the abbreviations for facilities charging the lowest and highest prices are given.) See Footnote 4 for data sources.

Item Illinois Massachusetts Washington Amazon

Commissary Local Retail Commissary Local Retail Commissary Local Retail

VO5 shampoo

12.5 oz. bottle $1.25 (LIN) to $1.69 (VIE) $0.99 (Jewel, Chicago) $1.38 $1.29 (Star Market, Cambridge) $1.71 (no size specified) $1.19 (Bartell’s Drugstore, Seattle) $4.88

Bic twin razor (single) $0.12 (HIL) to $0.18 (LIN) $0.35 (based on $3.49 for pkg of 10) (Jewel) $0.15 Unable to locate; comparable product (Gillette) available @ $1.20 (based on $11.99/pk of 10) $0.22 $1.20 (based on 5.99 for pkg of 5) (Bartell’s) $0.57 (based on $5.72 for pkg of 10)

Maruchan beef ramen $0.25 (multiple locations) $0.34 (based on $1 for pkg of 3) (Jewel) $0.40 $0.59 (Star Market) $0.25 or $0.29 (no brand specified) $0.89 (IGA Seattle) $0.71 (based on $16.99 for case of 24)

Mrs. Dash

2.5 oz. bottle $2.98 (multiple) to $3.26 (multiple) $2.99 (Jewel) $2.40 $3.49 (Star Market) not available $4.09 (IGA Seattle) $2.94

The other thing to keep in mind when comparing commissary prices to the free world is that people in prison have drastically less money to spend. So, while $1.87 may sound like a fair price to pay for a month’s worth of dental floss, the transaction feels very different from the perspective of someone in a Massachusetts prison who earns 14 cents per hour and has to work over 13 hours to pay off that floss. Or, to consider a different scenario: the average person in the Illinois prison system spends $80 a year on toiletries and hygiene products — an amount that could easily represent almost half of their annual wages.

Privatization can take different forms

When a prison system’s commissary is run by a private company, it raises logical concerns about fairness and coercion. In 2016, when one of the largest prison food service/commissary companies (Trinity Services Group) merged with another dominant commissary company (Keefe Group), we expressed concerns about the concentration of power and diminished competition — and quality — that would result. The passage of time has confirmed these fears: by 2017, maggots, dirt, and mold were reported in meals served by Trinity; these quality problems along with small portions led to multiple prison protests and $3.8 million in fines for contract violations in Michigan alone.

But exploitation can occur even if a system is not fully privatized. Of the three states we examined, only Massachusetts has a contractor-operated commissary system. It also has the highest per-person average commissary spending. It is tempting to conclude that the profit motive of commissary contractors leads to higher mark-ups and thus higher per capita spending, but we would need a larger sample size to test this hypothesis. What is notable in our three-state survey is that Illinois, with its state-run commissary, had per capita sales almost as high as Massachusetts’ contractor-run system, so a state-run system is clearly not a panacea. In addition, per capita spending in Washington and Illinois are so dramatically different that there must be other significant factors beyond outsourcing.

Arguably the most important privatization-related information in this study comes from Illinois. The Illinois prison commissary system has also been subject to harsh criticism for poor purchasing policies. In a 2011 report on commissary shortcomings, the Illinois Procurement Policy Board noted that only nineteen vendors provided 91% of all the items (measured by dollar amount) sold in the commissary. Among this handful of dominant providers, the one with the largest share was none other than Keefe, which accounted for 30% of the commissary’s spending. Thus, if Illinois is any indication, it appears that Keefe is positioned to make money even in states that have not privatized the operation of their prison commissaries.

The future of commissary: digital sales

Incarceration is becoming increasingly expensive — especially for those behind bars and their families. While prisons find new ways to shift the costs of corrections to incarcerated people (think medical co-pays and pay-to-stay fees), vendors are aggressively pushing new digital products that will further monetize incarcerated people.

This new breed of digital sales can take different forms. Sometimes this consists of “free” computer tablets that offer subscription based music streaming or ebooks. Other times, people must buy tablets or MP3 players and then pay for digital content. Given monopoly contracts and a captive market, prison and jail telecommunications providers are able to generate revenues far greater than similar companies in non-prison settings.

Some states appear to separate digital sales from the prison commissary, while others sell music downloads and other digital content through the commissary. Of the three states we looked at, Illinois was the only system that included digital sales in its commissary reports. The Illinois DOC contracts with GTL to provide electronic messaging and, apparently, digital music downloads. We say “apparently” because there is no reference to music downloads on the Illinois DOC website, but based on the sales figures, music sales seem to be a substantial money-maker:

Table 4. Of the three sampled states, only Illinois included sales figures from the emerging market of digital sales in its commissary reports. In that state alone, sales of electronic messages, music, and hardware, such as MP3 players, topped $1 million in 2016-2017.

Description Inventory Item Qty Sold Gross Sales

Electronic messaging Prepaid bundles of 1 or 20 messages 12,443 $35,301

Music Unclear 82,374 838,947

Hardware MP3 players and accessories 3,171 267,550

TOTAL $1,141,798

Price-gouging in commissaries is concentrated in the digital realm

Digital commissary illustration Illustration by Elydah Joyce

The pricing information discussed earlier provides evidence of an important fact: commissaries can afford to sell goods at prices comparable to or lower than free-world stores even while absorbing extra security-related costs (such as secure warehouses) and reaping healthy corporate profits. It appears prisons are ignoring these advantages when evaluating the prices of new digital products. As a prime example, the Massachusetts DOC signed a new contract with Keefe about a year ago, which includes electronic messaging and MP3 downloads. In stark contrast to the generally reasonable prices found in the commissary, Keefe’s digital music is priced at $1.85 per song, which is far higher than prices found on services like iTunes, Amazon, or Google Music (and more than can be explained by 5¢ kickback the DOC pockets for each song).

Emerging digital sales market lacks transparency

(expand)

The price disparity for digital items is even more confusing when you consider that delivering an MP3 file raises fewer security concerns than delivering a box of cereal to a prison commissary. The cereal box can theoretically be used to hide contraband, while an MP3 cannot. Of course, operating a digital music platform requires a robust IT security plan, but this is true of any service, whether it operates in the free world or only in prison. Indeed, in some ways, Keefe has less exposure to IT-based threats because much of its system operates on a closed network of kiosks and MP3 players, over which it exercises complete control (as opposed to Apple, which makes its iTunes store available to pretty much anyone with a computer and an internet connection). Thus, it is both paradoxical and troubling that Keefe can manage to price junk food and toiletries at or below standard retail prices, but charges nearly double the typical price for a digital music download.

Conclusion

Questions for future research

(expand)

Although it’s tricky to say how commissaries “should” ideally operate, their sales records ought to raise multiple concerns for justice reform advocates. If people in prison are resorting to the commissary to buy essential goods, like food and hygiene products, does it really make sense to charge a day’s prison wages (or more) for one of these goods? Should states knowingly force the families of incarcerated people to pay for essential goods their loved ones can’t afford, often racking up exorbitant money transfer fees in the process?

Conversely, when people in prison buy “nonessential” digital services, policymakers should compare the costs of those services to free-world prices. Marking up the cost of digital services for incarcerated people in order to make a quick profit - particularly in a time when these services are near-ubiquitous and generally cheap - is unquestionably exploitative.

In the long term, when incarcerated people can’t afford goods and services vital to their well-being, society pays the price. In the short term, however, these costs are falling on families, who are overwhelmingly poor and disproportionately come from communities of color. If the cost of food and soap is too much for states to bear, they should find ways to reduce the number of people in prison, rather than nickel-and-diming incarcerated people and their families.

Acknowledgements

This report was made possible by the generous contributions of individuals across the country who support justice reform. Individual donors give our organization the resources and flexibility to quickly turn our insights into new movement resources.

The author wishes to thank his Prison Policy Initiative colleagues for their feedback and assistance in the drafting of this report. Bridget Doyle, Hannah McKinney, and Sanndy Teran provided research assistance for price comparisons in Illinois and Massachusetts. Elydah Joyce created the illustrations.

About the author

Stephen Raher is an attorney in Oregon who works with the Prison Policy Initiative on projects at the intersection of criminal justice and finance or criminal justice and telecommunications. He began volunteering with us in 2015. Since then, he has written extensively about exploitative prison “services” including electronic messaging,” release cards, tablet computers, and money transfers. On the subject of commissaries, Stephen authored a 2016 investigation of the size of the commissary market just as two commissary giants prepared to merge.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization is most well-known for its big-picture publication Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie that helps the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform. This report builds upon the organization’s work advocating for fairness in industries that exploit the needs of incarcerated people and their families, including those that control prison and jail telephone calls, video calls, electronic messages, release cards, and money transfers.

Footnotes

The three states we sampled reflect a diversity of sizes and commissary management styles. Specifically, the size of the incarcerated population ranges from approximately 9,500 in Massachusetts (the thirty-third largest prison system in the country) to roughly 42,600 in Illinois (the eighth largest system). Washington is in the middle of the pack — the twenty-sixth largest state prison system, at 9,400 people. Illinois and Washington both use state-operated commissaries, while Massachusetts outsources its commissary operations (the current holder of the contract is the Keefe). ↩

The time periods covered by the sales data are as follows: 12 months ending June 2016 (Massachusetts), 12 months ending September 2017 (Illinois), and 12 months ending October 2017 (Washington). ↩

In 2016, we estimated per-person commissary sales at $647, based on data from the 2013 multi-state survey by the Association of State Correctional Administrators. That survey’s results, along with all other previously publicly available survey results from ASCA, have since disappeared from the association’s website. ↩

Commissary sales data came from the following sources:

Illinois: item usage reports and price lists for each Illinois DOC facility, provided in response to Illinois Freedom of Information Act request.

Massachusetts: DOC commissary usage report, published as part of Request for Response BD-17-1025-DOCFS-FISCM-00000009260.

Washington: commissary usage report provided in response to Washington Public Records Act request.

The above reports provided us with a list of each commissary’s inventory items, prices, and number of units sold in the relevant time period. To examine spending by category, we assigned each inventory item a category. To do this, we took the relevant point of sale expenditure classes used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index survey, and condensed them into the eleven categories used in the per capita sales table. To benefit other researchers who wish to apply this methodology to other states in a comparable way, please see our table mapping our broad categories to the detailed Consumer Price Index survey classes.

To calculate per capita purchases, we used population data from the following sources:

Illinois: monthly population for the twelve months of the inventory usage report was averaged. Data was collected from Ill. Dept. of Corr., Quarterly Report (Jan. 2018).

Massachusetts: average of monthly populations reported in FY 2016 DOC census, published as part of Request for Response BD-17-1025-DOCFS-FISCM-00000009260 (includes civil commitment patients at Bridgewater State Hospital).

Washington: population figure is an average of reported populations for the months December 2016 through June 2017, and September 2017. Data for December 2016 through June 2017 comes from Wash. Dept. of Corr., “Average Daily Population of Incarcerated Individuals, FY 2017” (Pub No. 400-RE002) (Sept. 2017); population for September 2017 comes from “Washington Dept. of Corr. Fact Card” (Pub. No. 100-QA001) (Sept. 30, 2017). ↩

Unfortunately, toilet paper rationing occurs with some regularity. In addition to the Arkansas case referenced in the text, there have been reports of limiting or withholding toilet paper in federal prisons and at least four other states: New York, Florida, Kansas, and Colorado. ↩

Mass. Dept. of Corr. Policy 750.11(2). ↩

Wages of $1 per day are based on the low end of Massachusetts’s pay scale for incarcerated people (typically $5-10 per week), as reported in our 2017 survey. ↩

According to our 2017 survey, Washington prisons pay incarcerated workers “up to $55 per month” (up to $660 per year), Illinois pays $15-$75 per month ($180-$900 per year), and Massachusetts pays $5 to $35 per week ($240-$1820 per year). Because we do not have data on the median wages or distribution of wages in each state, we cannot precisely estimate the annual wage differences between “average” incarcerated workers in each state. ↩

See Mary Fainsod Katzenstein & Maureen R. Waller, Taxing the Poor: Incarceration, Poverty Governance, and the Seizure of Family Resources, 13 Perspectives on Policy, 638, 639 (Sept. 2015) (“Government ‘seizure’…is a process through which state entities, in collaboration, often, with their corporate partners, act knowingly but in unseen ways to leverage money from families, partners, and friends of the prospectively, currently, or formerly incarcerated poor…. The radical innovation in this most recent means of poverty governance is the outright cash extraction that draws on ties of family dependency within the poorest stratum of American society.”) ↩

In Washington, an incarcerated person is considered “indigent” if they have “less than a ten-dollar balance of disposable income in his or her institutional account on the day a request is made to utilize funds and during the thirty days previous to the request.” Wash. Admin. Code 137-55-020(2). Washington DOC policy allows indigent people to obtain one tube of toothpaste every 60 days (or roughly 6 times per year) Id. 137-55-040(2). Commissary data show 33,870 tubes of “indigent toothpaste” distributed in a year. This would suggest an indigent population of roughly 5,500 (i.e. 33,870 units divided by 6 annual distributions, which equals 5,568 people), or about one-third of the state’s prison population. But using the same formula for “indigent soap” (65,310 units, with people allowed one new bar every week) suggests an indigent population of approximately 1,200 (less than 10% of the population). In other words, sales information for “indigent items” indicate that there is a substantial indigent population, but our efforts to interpolate the number of people falling in this category are inconclusive. ↩

Our price analysis is based on comparisons of retail prices before sales tax. We believe this methodology does not present any issues concerning Massachusetts and Washington, because commissaries in those states do not appear to enjoy any sales tax advantage. In particular, Massachusetts requires that its commissary vendor collect sales tax in the same manner as a regular retailer. See Mass. Dept. of Corr. Policy 476.05(6).) Washington’s DOC does not have an explicit policy, but there does not appear to be any sales tax exemption that would apply to commissaries (many food items in the Washington commissary are likely exempt from sales tax under Rev. Code Wash. 82.08.0293; however, this exemption would also apply in a free-world store). Illinois is the one state in our sample where commissaries may enjoy a sales tax advantage. The Illinois Department of Revenue appears to have interpreted state law as exempting prison meal and commissary sales from sales tax, provided that the facility itself (and not a contractor) is the seller. See Ill. Dept. of Rev., Gen. Info Letter 17-0004-GIL (Feb. 6, 2017) (citing Ill. Comp. Stat. 120/1’s exemption for sellers “organized and operated exclusively for charitable, religious or educational purposes”). ↩

This example is based on the following facts: the Massachusetts DOC commissary sells a package of 30 “floss loops” for $1.87. Each loop is a single-use disposable flossing device. The commissary sold 8,522 packages of these floss loops from June 2015 through June 2016, yielding gross sales of $15,936.14. Wages of 14c per hour (or $1 per day) are based on the low end of Massachusetts’s pay scale for incarcerated people, as reported in our 2017 survey. ↩

This example is based on Illinois’s annual average hygiene spending of $80 per person. The low end of prison wages in Illinois is 9c per hour, or $187 per year (if one were to optimistically assume 40 working hours per week). ↩

Also, the data we used here for Massachusetts come from the fiscal year ending June 2016. In April 2017, Massachusetts Department of Corrections signed a new contract with Keefe Group that changed the commissary pricing schedule and would purportedly result in lower price tags. ↩

Another reason to suspect that the Illinois prices are for digital downloads, not a subscription service, is that the price for a single “music inventory item” is $1.80, which is almost the same price that Keefe charges for an MP3 download under its new Massachusetts contract ($1.85). In other words, $1.80/song might be the prevailing market price for music downloads in prison. ↩

Illinois’s inventory report shows that the commissary sold 3,911 “single use” electronic messages (30¢ each), and 8,532 bundles of 20 messages ($4 each), with total sales proceeds of $35,301. These sales represent 174,551 electronic messages (i.e., 3,911 + (8,532 x 20)). The average price of 20.2¢ per message simply reflects the total revenue divided by the number of messages sold. ↩

***

MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS

CANTEEN OPERATIONS

POLICY NUMBER 02-10

AGENCY WIDE

INITIAL DATE 12-01-1982

EFFECTIVE DATE 04-01-2014

ACA STANDARDS: 2-CO-1B-12, 2-CO-1B-13. 4-4042, 4-4043, 4-ACRS-7D-29

STATUTES: 47-5-58, 47-5-109

NON-RESTRICTED

POLICY:

It is the policy of the Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) to provide canteen services to eligible inmates.

DEFINITIONS:

Inmate Welfare Fund - A fund established and maintained for the benefit and welfare of inmates.

Canteen Committee - Select MDOC staff members appointed for the purpose of providing an agency wide management consensus on canteen operations and procedures.

PRECEPTS:

Administration of Correctional Agencies (Central Office): Written policy provides for the operation of commissary or canteen service within the agency facilities (2-CO-1B-12).

MDOC will provide commissary or canteen services and the operation will be governed by an agency wide Canteen Committee consisting of representatives from the following correctional divisions:

*State Institutions

*Private Prisons

*County Regional Prisons

*Community Work Centers

The Canteen Committee will:

*Determine what items canteens will sell

*Approve prices

*Set canteen policy and procedures

All actions of the Canteen Committee will be subject to the review and approval of the Deputy Commissioner of Institutions and the Deputy Commissioner of Community Corrections.

Canteen Operations

Adult Correctional Institutions: An inmate commissary or canteen is available where inmates can purchase approved items that are not furnished by the facility. The canteen/commissary's operations are strictly controlled using standard accounting procedures [4-4042].

Adult Correctional Institutions: Commissary/canteen funds are audited independently following standard accounting procedures, and an annual financial status report is available as a public document [4-4043].

Adult Correctional Institutions: Where a commissary or canteen is operated for offenders, canteen funds are audited independently following standard accounting procedures. An annual financial status report is available as a public document [4-ACRS-7D-29].

The MDOC Canteen Manager will develop a canteen management manual that addresses, at a minimum, the following:

*Selling process

*Visitation Center process

*Bagging process

*Receipt of merchandise from vendors

*Price list

*Profit margins

*Accounting procedures

*Financial statements

The canteen manual will be subject to the approval of the Deputy Commissioner of Administration and Finance and other applicable authorities.

Offender Access

Canteen space/services will be made available to offenders for the purchase of pre-approved items.

Each custody level will be provided with a list of approved canteen items specific to their custody status.

Canteen Inventory Prohibitions

*Caustic substances

*Toxic substances

*Metal items or containers

*Glass items or containers

All items and containers will be made of plastic.

Maximum Canteen Expenditures by Custody/Status

*Minimum Custody - One hundred dollars ($100) per week

*Medium Custody - One hundred dollars ($100) per week

*Close Custody - One hundred dollars ($100) every two weeks

*Death Row - One hundred dollars ($100) per week

*Administrative Segregation - Fifty dollars ($50) per month for personal hygiene items and stamps.

*RID inmates - As designated by RID Administration and approved by the Deputy Commissioner of Institutions.

The Warden or designee will establish the frequency of canteen calls for their areas except where specified by policy or procedure.

Canteen Forms

Unit Administrators or designees will be responsible for ensuring inmates receive Central Canteen order forms.

Unit Administrators will also be responsible for ensuring the completed order forms are available for pickup by the canteen staff on the designated day.

Inmate Identification

Inmates must show their valid MDOC identification card before receiving items from any MDOC canteen.

MDOC staff who are responsible for canteen operations will ensure that this procedure is strictly enforced.

Cashless System

Canteens for all MDOC facilities and private prisons will operate on a cashless system. Inmate canteen workers will not be permitted to access or operate the inmate accounting system, operate computers or cash registers, or handle money while working in the canteen.

Inmate Welfare Fund

Canteens for MDOC facilities and private prisons will operate as profit-making centers with all profits going to the Inmate Welfare Fund.

Accounting Protocols

Administration of Correctional Agencies (Central Office): Written agency policy provides that commissary/canteen funds are audited independently following standard accounting procedures and an annual financial report is available (2-CO-1B-13).

The Accounting protocols for canteens will include the following:

*Canteen's operations will be subject to strict standard accounting procedures

*Canteen funds will be independently audited in accordance with procedures

*Annual financial status report will be made available for public access

*Canteen staff will inventory all canteens on a quarterly basis

Documents Required:

As required by this policy and through chain of command.

Enforcement Authority

All standard operating procedures (SOPs) and/or other directive documents related to the implementation and enforcement of this policy will bear the signature of and be issued under the authority of the Deputy Commissioner of Administration and Finance.

Review and Approved for Issuance

[Signatures of General Counsel and Commissioner. 3/19/2014 and 3/20/2014.]

***

http://www.mdoc.ms.gov/Inmate-Info/Documents/PriceList_2015_.pdf

Coffee, Grains $4.33

Coffee, Instant $4.33

Coffee, Freeze Dried $4.57

Coffee, Decaf $0.43

Coffee, Cappuccino French Vanilla $2.59

Coffee, Single Serve $0.28

Water, $0.95

Soft Drink, Faygo $1.24

Soft Drink, Coke $1.63

Soft Drink, Diet Coke $1.63

soft drink,pepsi $1.63

Soft Drink, Sprite $1.63

Orange Drink Singles $0.34

Peach Drink Singles $0.34

Fruit Punch Singles $0.34

Lemonade Singles $0.34

Tea Singles $0.58

Cocoa Singles $0.48

Men's Boxers $2.41

Men's Boxers $2.41

Men's Boxers $3.13

Men's Boxers $3.27

Men's Boxers $3.27

Men's Boxers $3.27

Men's Boxers $3.27

Men's T-Shirts $2.89

Men's T-Shirts $3.61

Men's T-Shirts $3.61

Men's T-Shirts $4.82

Men's T-Shirts $4.82

Men's T-Shirts $4.82

Men's T-Shirts $4.82

Men's T-Shirts $4.82

Thermal Sets (Men/Women) $9.63

Thermal Sets (Men/Women) $9.63

Thermal Sets (Men/Women) $9.63

Thermal Sets (Men/Women) $9.63

Thermal Sets (Men/Women) $9.63

Exhibit C-1

Mississippi Department of Corrections

Schedule Verifying Price Amendment 42% vs. 32%

Price

Thermal Sets (Men/Women) $9.63

Thermal Sets (Men/Women) $9.63

Thermal Sets (Men/Women) $9.63

Bleached Tube Socks $1.20

Laundry Bag $2.66

Shower Shoes, Men/Women (One Pair) $1.93

Shower Shoes, Men /Women(One Pair) $1.93

Shower Shoes, Men /Women(One Pair) $1.93

Tennis Shoe Men (One Pair) $23.10

Tennis Shoe Men (One Pair) $23.10

Tennis Shoe Men (One Pair) $23.10

Tennis Shoe Men (One Pair) $23.10

Tennis Shoe Men (One Pair) $23.10

Tennis Shoe Men (One Pair) $23.10

Tennis Shoe Men(One Pair) $23.10

Sports Bra $3.08

Sports Bra $4.04

Sports Bra $4.04

Sports Bra $4.04

Sports Bra $4.04

Sports Bra $4.82

Sports Bra $4.82

Sports Bra $4.82

Sports Bra $4.82

Women Cotton Panties $1.78

Women Cotton Panties $1.78

Women Cotton Panties $1.78

Women Cotton Panties $1.78

Women Cotton Panties $1.78

Women Cotton Panties $1.97

Women Cotton Panties $1.97

Women Cotton Panties $1.97

Women Cotton Panties $1.97

Women Cotton Panties $1.97

Knee Hi Sheer $0.86

Curling Iron $12.04

Curling Iron $12.04

Hair Dryer $14.45

Flat Iron $15.89

Curling Iron (Gold Barrell) $9.62

Exhibit C-1

Mississippi Department of Corrections

Schedule Verifying Price Amendment 42% vs. 32%

Price

Comb $0.24

Bobby Pins (Black) $0.86

Women's Professional Style brush $0.47

Hair Spray $1.63

Styling Gel (Black) (clear container) $2.89

Styling Gel (Pink/Clear) (clear container) $2.89

Clear Plastic Shower Cap $0.05

Royal Crown Sheen $3.08

Snap Over Rollers $1.92

Shampoo/Shave Gel/Body Wash-clear container $0.76

Dandruff Shampoo (clear container) $0.86

Conditioner (clear container) $0.76

Rubber Bands $0.47

Style Gel (clear container) $1.53

Mississippi Department of Corrections

Schedule Verifying Price Amendment 42% vs. 32%

Price

Noxema Skin Cream $3.55

Hand & Body Lotion (clear container) $0.86

Cocoa Butter Lotion (clear container) $0.86

Baby Oil (clear container) $1.82

Baby Lotion (clear container) $1.16

Petroleum Jelly (clear container) $1.83

Q-Tips $1.73

Plastic Spoon $0.10

Insulated Mug w/Lid (clear) $3.37

Cereal Bowl w/Lid $1.16

Sweet & Low $0.82

Creamer $0.82

Sugar $0.82

Salt $0.82

Pepper $0.82

Mayonnaise $1.49

Mustard $1.20

Ketchup $1.20

Hot Sauce $1.49

Dill Pickle $1.25

Jalapeno Pepper Slices $0.63

Picante Sauce $2.79

Honey $1.92

Grape Jelly $3.47

Cushion Shoe Insoles (size 7 - 12) $1.93

Playing Cards $2.41

Double Six Dominoes $3.84

Watch Battery - ECR2016 $0.86

Watch Battery - 376/377 $0.86

AA Batteries $4.33

AAA Batteries $4.33

Clear Wrist Watch $4.71

Butterfinger $1.34

Now & Later Assorted $1.43

Peppermints $1.43

M&M Plain $1.34

M&M Peanut $1.34

Payday $1.34

Jolly Rancher Assorted $1.44

Reese Peanut Butter Cup $1.34

Exhibit C-1

Mississippi Department of Corrections

Schedule Verifying Price Amendment 42% vs. 32%

Price

Snickers $1.34

Kit Kat Bar $1.34

Baby Ruth Bar $1.34

Zero Bar $1.34

Skittles Original $1.34

Digby's All Star $0.95

Butterscotch Buttons $1.34

Lemon Drops $1.34

Rootbeer Barrels $1.15

Sour Fruit Balls $1.34

Toasted PNB Crackers $0.72

Ched Cheese Crackers $0.72

Salted Peanuts $0.95

Wham Wham (Bear Claw) $1.40

Honey Bun $1.43

Iced Honey Bun $1.53

Blueberry Cheese Danish $1.24

Strawberry Cheese Danish $1.24

Cinnamon Roll $0.95

Moon Pies - Vanilla $0.91

Moon Pies - Banana $0.91

Strawberry Toaster $1.05

Brown Sugar Cinnamon Toaster $1.05

Oatmeal Crème Pie $3.26

Duplex Cremes $1.53

Vanilla Cremes $1.53

Peanut Butter Cremes $1.53

Chocolate Chip Cookies $1.53

Orange Pineapple Cremes $1.53

Iced Oatmeal Cremes $1.53

Jalapeno Cheese Spread packet $2.99

Cheddar Cheese Spread packet $2.99

Mac & Cheese packet $1.40

Spicy Cheesy Rice packet $0.95

Spicey Cheesy Refried Beans packet $0.95

Spicey Cheesy Refried Beans/Rice packet $1.54

Refried Beans w/Jalapenos packet $2.88

Flour Tortilla 6/ct packet $2.11

Spam Singles packet $2.65

Summer Sausage packet $3.84

Exhibit C-1

Mississippi Department of Corrections

Schedule Verifying Price Amendment 42% vs. 32%

Price

Spicey Summer Sausage packet $3.84

Turkey Summer Sausage packet $3.84

Macaroni & Cheese Dinner packet $1.44

Twin Beef Stick $0.95

Beef & Cheddar Stick $0.95

Chicken Vienna Sausage packet $1.92

Chili with Beans packet $2.78

Chilli No Beans packet $2.78

Beef Stew packet $2.78

Lasagna packet $2.78

Spicy Ground Beef packet $1.82

Microwave Popcorn Butter $1.05

Sloppy Joe packet $1.82

Ramen Hot/Spicy Noodles $0.53

Ramen Beef Noodles $0.53

Ramen Chicken Noodles $0.53

Snack Crackers $3.07

White Rice $1.92

Brown Rice $1.92

Hot Salami $2.89

Pepperoni Slices $1.92

Pnutbutter & Jelly Squeeze $0.95

Creamy Peanut Butter (4) $0.67

Grape Jelly $3.47

Cinnamon Squares bag $2.68

Peanut Butter Wafers $3.36

Chips $1.15

Skins $1.72

Doritos $1.24

Tortilla Chips $3.37

Cheetos $1.34

Saltine crackers $3.36

Granola Bar $0.87

Sardines in Soybean Oil packet $1.92

Fillet of Mackeral packet $2.40

Light Tuna packet $2.78

Sardines in hot tomato sauce packet $1.92

Triple Antiobiotic Ointment $2.88

Chapstick $1.34

Tylenol $0.95

Exhibit C-1

Mississippi Department of Corrections

Schedule Verifying Price Amendment 42% vs. 32%

Price

Bayer Aspirin $0.95

Rolaids $1.20

Eye drops (clear container) $2.02

Cough Drops-Honey Lemon $1.20

Oral Gel $1.53

Hydrocortisone Cream $1.92

Muscle Rub $1.53

Daily Multi-Vitamins $2.88

Advil $0.95

Antifungal Crème $1.83

Laxative $1.93

Antifungal Powder $1.73

Reading Glasses $0.47

Reading Glasses $0.47

Reading Glasses $0.47

Reading Glasses $0.47

Reading Glasses $0.47

Reading Glasses $0.47

Reading Glasses $0.47

Reading Glasses $0.47

Reading Glasses $0.47

Other posts by this author

|

2023 may 31

|

2023 mar 20

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

More... |

Replies