Transcription

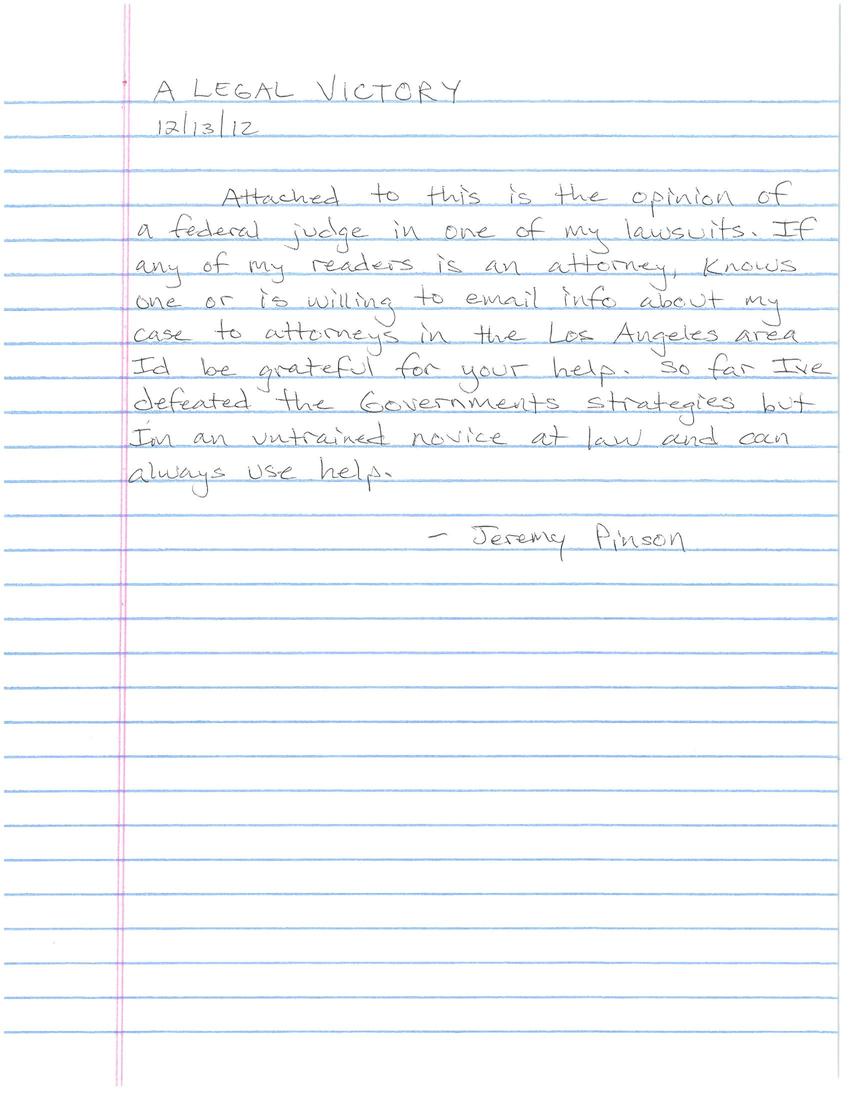

A LEGAL VICTORY

12/13/12

Attached to this is the opinion of a federal judge in one of my lawsuits. If any of my readers is an attorney, knows one or is willing to email info about my case to attorneys in the Los Angeles area I'd be grateful for your help. So far I've defeated the government's strategies but I'm an untrained novice at law and can always use help.

- Jeremy Pinson

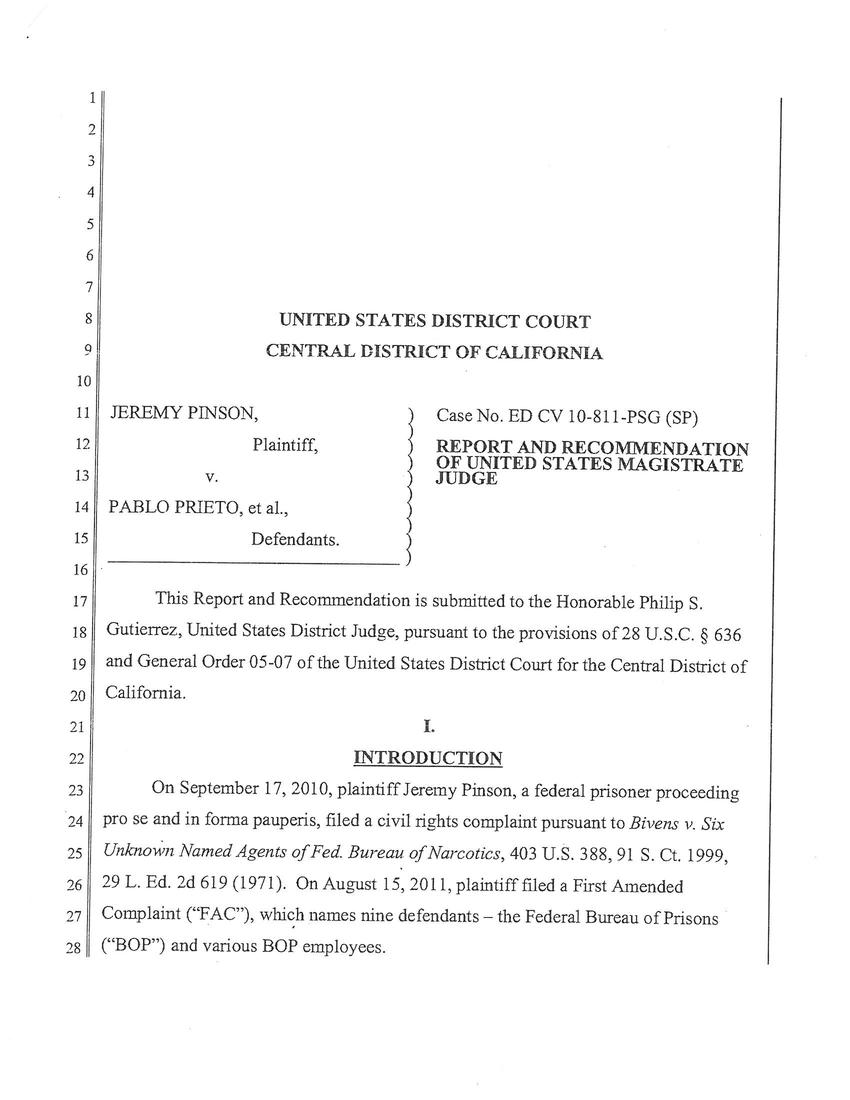

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

Case No. ED CV 10-811-PSG (SP)

REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION OF UNITED STATES MAGISTRATE JUDGE

JEREMY PINSON, Plaintiff, vs. PABLO PRIETO, et al., Defendants

This Report and Recommendation is submitted to the Honorable Philip S. Gutierrez, United States District Judge, pursuant to the provisions of 28 U.S.C. 636 and General Order 05-07 of the United States District Court for the Central District of California.

I.

INTRODUCTION

On September 17, 2010, plaintiff Jeremy Pinson, a federal prisoner proceeding pro se and in forma pauperis, filed a civil rights complaint pursuant to Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Fed. Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388, 91 S. Ct. 1999, 29 L. Ed. 2d 619 (1971). On August 15, 2011, plaintiff filed a First Amended Complaint ("FAC"), which names nine defendants - the Federal Bureau of Prisons ("BOP") and various BOP employees.

The FAC asserts a single claim: that defendants acted with deliberate indifference to plaintiff's safety in violation of the Eighth Amendment. FAC at 5. In addition to the three defendants named in the original complaint (who have already been served), the FAC names six new defendants. The three served defendants named in the FAC are: (1) Pablo Prieto, a Correctional Counselor and the U.S. Penitentiary at Victorville ("USP Victorville"); (2) Richard Bourn, a Captain and the USP Victorville; and (3) Josh Halstead, an SIS Lieutenant at USP Victorville. The six new defendants are: (1) Joseph Norwood, the Warden at USP Victorville; (2) V. Graham, an Officer at USP Victorville; (3) Robert McFadden, a BOP Regional Director in Stockton, California; (4) BOP; (5) John Dignam, BOP Chief of Internal Affairs in Washington, D.C.; and (6) Delbert Savers, BOP D.S.C.C Chief in Grand Prairie, Texas. Id at 3-4.

On October 24, 2011, the court screened the FAC and found it subject to dismissal for failure to state a claim against defendants Graham, Dignam, and Savers, but granted plaintiff leave to amend. See Oct 24, 2011 Order. On November 7, 2011, plaintiff filed a Voluntary Partial Dismissal - dismissing defendants Graham, Dignam, and Savers - and elected to proceed on the FAC with the remaining defendants.

On March 23, 2012, defendant BOP filed a Motion to Dismiss the FAC under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1) and 12(b)(6) ("BOP Motion"), arguing that: (1) the court lacks subject matter jurisdiction over plaintiff's claim for declaratory relief; and (2) the FAC fails to state a claim for injunctive relief that can be granted. BOP Mot. at 4-7. Because plaintiff seeks only declaratory and injunctive relief against BOP, BOP seeks dismissal due to the FAC's failure to state a claim for relief that can be granted against BOP. Id at 3-7.

On March 26, 2012, defendants McFadden and Norwood moved to dismiss the FAC under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) ("M&N Motion"), arguing the FAC fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted against them. M&N Mot. at 6-9. Defendants McFadden and Norwood also argue they are entitled to qualified immunity. Id.

On April 2, 2012, plaintiff opposed the BOP Motion ("First Opposition"), and defendant BOP filed a Reply on April 16, 2012. Plaintiff opposed the M&N Motion on April 13, 2012, and defendants McFadden and Norwood filed their Reply on April 26, 2012. The court also stayed this case from April 27 to June 13, 2012 based on plaintiff's request and defendant's non-objection.

As described in more detail below, the court finds that plaintiff is not entitled to the declaratory or injunctive relief he seeks against BOP. The court also finds that the FAC sufficiently states an Eighth Amendment claim against defendants McFadden and Norwood. As such, it is recommended that defendant BOP's Motion to Dismiss be granted, and defendants McFadden's and Norwood's Motion to Dismiss be denied.

II

PERTINENT ALLEGATIONS OF THE FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT

Plaintiff was convicted in federal court and sentenced to 240 months in prison in 2007. FAC at 7. After plaintiff was termed a "snitch" by other inmates and assaulted, plaintiff was reassigned to USP Florence in Colorado. Id at 7-8. At USP Florence, plaintiff engaged in certain gang activity, and then attempted to leave his gang. Id at 8. Defendant BOP denied plaintiff's request for protection from the gang and its associates. Id. On or about December 12, 2007, plaintiff was beaten unconscious by his cellmate at USP Florence. Id.

On February 14, 2008, plaintiff was transferred to USP Victorville. FAC at 8. Defendants Norwood and McFadden were responsible for supervising and training staff, and for the security plans at USP Victorville, and they were notified of the details concerning every gang-related assault or murder at the prison. Id. Defendants Bourn and Halstead were responsible for security, and for investigating assaults and murders, but failed to investigate or take steps to stop the illegal activity and protect inmates. Id at 9. Defendant Prieto actively assisted the Mexican Mafia in extortion, drug trafficking and gang activity. Id.

On February 15, 2008, during a classification review, plaintiff warned defendants Bourn and Halstead he would be attacked by his gang, but they refused to segregate him. FAC at 9-10. Although the gang in his assigned unit was not yet aware of plaintiff's history, plaintiff continued to request protection, but defendants Bourn, Halstead and Norwood denied his requests. Id. at 10.

Plaintiff began to file administrative grievances through defendant Prieto, who became upset by this. FAC at 10. Defendant Prieto provided an administrative response discussing plaintiff's sexuality and desire for protection to plaintiff's cellmate, who gave it to the Mexican Mafia. Id. The Mexican Mafia then ordered an assault on plaintiff. Id. The assault took place in a cell and caused bruises and swelling to plaintiff's face. Id. Defendants Bourn, Norwood and Halstead observed plaintiff's injuries, but refused to protect plaintiff. Id.

Shortly thereafter, the Mexican Mafia ordered plaintiff killed. FAC at 10. On April 9, 2008, five inmates armed with shanks entered plaintiff's cell and attempted to kill him. Id at 11. Plaintiff sustained severe injuries, including stab wounds and broken bones. Id. Immediately following the assault, defendants Norwood and Bourn attempted to house plaintiff with a member of the gang that had just assaulted him; plaintiff refused. Id.

After the April 9, 2008 assault, plaintiff attempted to help defendants Bourn, Halstead and McFadden investigate the assault. FAC at 11. Defendant McFadden rejected plaintiff's submission. Id. Defendants Bourn and Halstead interviewed gang allies and falsely reported on the incident to cover it up. Id. Defendant Norwood deliberately ignored plaintiff's pleas to refer the matter to the FBI. Id. No inmates were disciplined for the attempted murder. Id.

Based upon these allegations, plaintiff claims defendants were deliberately indifferent to his safety, in violation of the Eighth Amendment. Plaintiff requests: (1) compensatory damages of $5,000 against defendants Halstead, Bourn, Prieto, Norwood, and McFadden; (2) punitive damages of $2,500,000 against defendants Halstead, Bourn, Prieto, Norwood, and McFadden; (3) "Declaratory Judgment that Bureau of Prison is grossly inadequate in investigating gang activity and acting to segregate gangs, disrupt gang activity, prevent assaults, stop criminal activity in violation of the 8th Amendment" and (4) an injunction compelling BOP to: (a) "Consider placing plaintiff in Witness Security Program or state prison for his protection"; (b) "Formulate procedure to identify and segregate any inmate who is a member or associate of a prison gang until such time that person credibly renounces gang activity or that gang is no longer deemed a threat to the safety, security and order of correctional facilities"; and (c) "Fully debrief the plaintiff and refer all information provided to the Federal Bureau of Investigation [("FBI")] for criminal investigation".

III.

LEGAL STANDARDS

Under Rule 12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a defendant may move to dismiss a complaint for "failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted". A motion to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) "tests the legal sufficiency of a claim". Navarro v. Block, 250 F.3d 729, 732 (9th Cir. 2001). Dismissal for failure to state a claim "can be based on the lack of a cognizable legal theory or the absence of sufficient facts alleged under a cognizable legal theory". Balistreti v. Pacifica Police Dep't, 901 F.2d 696, 699 (9th Cir. 1990)

"When there are well-pleaded factual allegations, a court should assume their veracity and then determine whether they plausibly give rise to an entitlement to relief". Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 129 S. Ct. 1937, 1950, 173 L. Ed. 2d 868 (2009). But "the tenet that a court must accept as true all of the allegations contained in a complaint is inapplicable to legal conclusions. Threadbare recitals of the elements of a cause of action, supported by mere conclusory statements, do not suffice". Iqbal, 556 U.S. at 678 (citing Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 555, 127 S. Ct. 1955, 167 L. Ed. 2d 929 (2007)). The allegations made in a complaint must both "contain sufficient allegations of underlying facts to give fair notice and to enable the opposing party to defend itself effectively... [and] must plausibly suggest an entitlement to relief, such that it is not unfair to require the opposing party to be subjected to the expense of discovery and continued litigation". Starr v. Baca, 652 F.3d 1202, 1216 (9th Cir. 2011).

Where a plaintiff proceeds pro se in a civil rights case, the court must construe the pleadings liberally and afford the plaintiff any benefit of the doubt. Karim-Panahi v. L.A. Police Dep't, 839 F.2d 621, 623 (9th Cir. 1988). The rule of liberal construction is "particularly important in civil rights cases". Ferdik v. Bonzelet, 963 F.2d 1258, 1261 (9th Cir. 1992) (citation omitted). Nonetheless, in giving liberal interpretation to a pro se civil rights complaint, courts may not "supply essential elements of claims that were not initially pled". Ivey v. Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of Alaska, 673 F.2d 266, 268 (9th Cir. 1982). "Vague and conclusory allegations of official participation in civil rights violations are not sufficient to withstand a motion to dismiss". Id. (citations omitted); see also Jones v. Cmty. Redev. Agency, 733 F.2d 646, 649 (9th Cir. 1984) (finding conclusory allegations unsupported by facts insufficient to state a claim under 1983). "The plaintiff must allege with at least some degree of particularity overt acts which defendants engaged in that support the plaintiff's claim". Jones, 733 F.2d at 649 (internal quotation marks omitted).

The court must give a pro se litigant leave to amend his complaint "unless it determines that the pleading could not possibly be cured by the allegation of other facts". Lopez v. Smith, 203 F.3d 1122, 1127 (9th Cir. 2000) (en banc) (quotation marks and citations omitted). Thus, before a pro se civil rights complaint may be dismissed, the court must provide the plaintiff with a statement of the complaint's deficiencies. Karim-Panahi, 839 F.2d at 623-24. But where amendment of a pro se litigant's complaint would be futile, denial of leave to amend if appropriate. See James v. Giles 221 F.3d 1074, 1077 (9th Cir. 2000).

IV.

DISCUSSION

Preliminarily, plaintiff's assertion that defendants' motions are moot, or amount to improper motions for reconsideration of the court's October 24, 2011 Order Dismissing First Amended Complaint, is mistaken. The court's October 24th Order was nothing more than a screening order, in which the court sought to identify glaring deficiencies in the FAC pursuant to its obligations under 28 U.S.C. 1915(e)(2) and 1915A. It was not intended to, and did not, foreclose defendants' right to contest the adequacy of the FAC under Rule 12 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Accordingly, the court will consider defendants' motions.

A. BOP Should Be Dismissed from this Action

Plaintiff seeks a declaration that BOP is "grossly inadequate in investigating gang activity and acting to segregate gangs, disrupt gang activity, prevent assaults, stop criminal activity in violation of the 8th Amendment". FAC at 6. Plaintiff also seeks injunctive relief compelling BOP to: (1) consider placing plaintiff in Witness Security Program or state prison for his protection; (2) formulate procedures to identify and segregate any inmate who is a member or associate of a prison gang; and (3) fully debrief plaintiff and refer all information provided to the FBI for criminal investigation. Id. For the reasons detailed below, the court finds that plaintiff is not entitled to declaratory or injunctive relief against BOP and his claim against BOP should therefore be dismissed.

1. Plaintiff's Request for Declaratory Relief Should Be Stricken

A party does not have an absolute right to a legal determination of its claim under the Declaratory Judgment Act, 28 U.S.C. 2201. See United States v. Washington, 759 F.2d 1353, 1356 (9th Cir. 1985) (en banc) (per curiam). "A declaratory judgment, like other forms of equitable relief, should be granted only as a matter of judicial discretion, exercised in the public interest". Eccles v. Peoples Bank of Lakewood Vill., Cal., 333 U.S. 426, 431, 68 S. Ct. 641, 92 L. Ed. 784 (1948) (citations omitted); see Leadsinger, Inc. v. BMG Music Publ'g, 512 F.3d 522, 533 (9th Cir. 2008) ("Federal courts do not have a duty to grant declaratory judgment; therefore, it is within a district court's discretion to dismiss and action for declaratory judgment" (citations omitted)). Declaratory relief should be denied when "prudential considerations counsel against its use", or when the relief requested "will neither serve a useful purpose in clarifying and settling the legal relations in issue nor terminate the proceedings and afford relief from the uncertainty and controversy faced by the parties". Washington, 759 F.2d at 1357 (citations omitted). It is unnecessary to settle the entire controversy; it is enough if "a substantial and important question currently dividing the parties" is resolved. L.A. Cnty. Bar Ass'n v. Eu, 979 F.2d 697, 703-04 (9th Cir. 1992).

Here, in the event this action reaches trial and the jury returns a verdict in favor of plaintiff, that verdict will be a finding that plaintiff's Eighth Amendment rights were violated. But a declaration that BOP violated plaintiff's Eighth Amendment rights "will neither serve a useful purpose in clarifying and settling the legal relations in issue nor terminate the proceedings and afford relief from the uncertainty and controversy faced by the parties". See Washington, 759 F.2d at 1357. Indeed, as defendant notes, the declaratory relief plaintiff seeks amounts to an improper request for an advisory opinion regarding alleged gross inadequacies by BOP generally, going far beyond the scope of plaintiff's case. It would be improper for the court to issue such an advisory opinion. See Chicago & S. Air Lines v. Waterman S.S. Corp., 333 U.S. 103, 113-14, 68 S. Ct. 431, 92 L. Ed. 568 (1948).

Because plaintiff's request for declaratory relief is improper and cannot be granted, it should be stricken from the FAC without leave to amend.

2. The Court Lacks Jurisdiction to Grant Plaintiff's Request to Be Placed in the Witness Security Program or State Prison

It is well established that a federal court may issue an injunction only "if it has personal jurisdiction over the parties and subject matter jurisdiction over the claim; it may not attempt to determine the rights of persons not before the court". Zepeda v. United States Immigration and Naturalization Serv., 753 F.2d 719, 727 (9th Cir. 1985); see also In re Rationis Enters., Inc. of Panama, 261 F.3d 264, 267 (2d Cir. 2001) ("requirement that jurisdiction be established as a threshold matter springs from the nature and limits of the judicial power of the United States and is inflexible and without exception" (internal quotation marks and citation omitted)). Accordingly, "[u]nder Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d), an injunction binds only 'the parties to the action, their officers, agents, servants, employees, and attorneys, and... those persons in active concert or participation with them'". Zepeda, 753 F.2d at 727; see also Citizens Alert Regarding the Env't v. United States Envtl. Prot. Agency, 259 F. Supp. 2d 9, 17 n.7 (D.D.C. 2003), aff'd, 102 Fed. App'x 167 (D.C. Cir. 2004) (a district court is "powerless to issue an injunction against" an entity that is "not a party to [the] action"); Gilchrist v. Gen Elec. Capital Corp., 262 F.3d 295, 301 (4th Cir. 2001) ("any injunction entered against individuals is an in personam action that may be enforced against individuals only over whom the court has personal jurisdiction", unless the individuals "could be shown to have been 'in active concert or participation with' parties over the court ha[s] jurisdiction" (citations omitted)).

Here, in order to grant part of plaintiff's desired relief - to be considered for admission into the Witness Security Program - the court must be able to exercise jurisdiction over the Department of Justice's Criminal Division's Office of Enforcement Operations ("OEO"). It is OEO, not BOP, that determines who is admitted into the Witness Security Program. Opp'n, Eliezer Ben-Shmuel Decl. 10, Nov. 3, 2011, ECF No. 63; see also Mir v. Little Co. of Mary Hosp., 844 F.2d 646, 649 (9th Cir. 1988) ("it is proper for the district court to 'take judicial notice of matters of public record outside the pleadings' and consider them for purposes of the motion to dismiss" (citations omitted)). The court's jurisdictional reach fails to extend that far. OEO is not a party to this action. See FAC at 3-4. Plaintiff also does not contend, much less establish, that OEO is somehow acting "in active concert or participation with" defendants. See generally id. at 5-12. The court therefore lacks the authority to direct OEO to consider admitting plaintiff into the Witness Security Program.

With respect to plaintiff's request that BOP be ordered to consider transferring him to a state prison, plaintiff has no constitutional right to be incarcerated in a particular institution nor to be transferred from one facility to another. See Olim v. Wakinekona, 461 U.S. 238, 245, 103 S. Ct. 1741, 75 L. Ed. 2d 813 (1983) ("inmate has no justifiable expectation that he will be incarcerated in any particular prison"); see also Meachum v. Fano 427 U.S. 215, 224-25, 96 S. Ct. 2532, 49 L. Ed. 2d 451 (1976) ("Confinement in any of the State's institutions is within the normal limits or range of custody which the conviction has authorized the State to impose").

Moreover, where a prisoner is challenging conditions of confinement and is seeking injunctive relief, transfer to another prison renders the request for injunctive relief moot absent some evidence of an expectation of being transferred back. See Preiser v. Newkirk, 422 U.S. 395, 402-03, 95 S. Ct. 2330, 45 L. Ed. 2d 272 (1975); Johnson v. Moore, 948 F.2d 517, 519 (9th Cir. 1991) (per curiam). In this case, because plaintiff is challenging conditions of confinement at USP Victorville and is seeking injunctive relief to be placed in the Witness Security Program or transferred to state prison for his protection, his transfer from USP Victorville in May 2008 rendered his request for injunctive relief moot. See id.; see also FAC at 12.

3. Plaintiff's Request that BOP Formulate Procedures to Identify and Segregate Inmate Gang Members Is Not Relief Available in this Case

For injunctive relief to be granted in a civil action with respect to prison conditions, the relief must be "narrowly drawn, extend[] no further than necessary to correct the violation of the Federal right, and [be] the least intrusive means necessary to correct the violation of the Federal right". 18 U.S.C. 3626(a)(1). In this case, the harm plaintiff apparently seeks to prevent is harm inflicted on him by his former gang and the Mexican Mafia. See FAC at 9-12. But plaintiff's request that BOP formulate procedures to identify and segregate inmates who are members or associates of a prison gang reaches much farther than the harm at issue and extends to all prisoners. This is not a class action, and plaintiff has no right to assert claims on behalf of other inmates. See Simon v. Hartford Life, Inc., 546 F.3d 661, 664 (9th Cir. 2008) ("the privilege to represent oneself pro se provided by [28 U.S.C.] 1654 is personal to the litigant and does not extend to other parties or entities"); Oxendine v. Williams, 509 F.2d 1405, 1407 (4th Cir. 1975) ("it is plain error to permit this imprisoned litigant who is unassisted by counsel to represent his fellow inmates in a class action").

Because the relief plaintiff seeks would extend to prisoners other himself, and would "bind[] prison administrators to do more than the constitutional minimum", the court may not grant plaintiff's desired relief. See Gilmore v. California, 220 F.3d 987, 999 (9th Cir. 2000). In addition, as with the housing relief plaintiff requests, plaintiff's request for relief with respect to prisoner classification is moot, since plaintiff has been transferred to a prison other than the one with the conditions at issue in this case. See Preiser, 422 U.S. at 402-03; Johnson, 948 F.2d at 519. For these reasons, plaintiff's request for relief affecting BOP gang classification procedures cannot be granted.

4. The Court Has No Legal Basis to Grant Plaintiff's Request to Be Fully Debriefed and for the Information to Be Forwarded to the FBI

Plaintiff argues that "[t]he Crime Victims Rights Act confers upon Plaintiff the right to confer with the government and the right to be protected from his attackers[;] these rights may be enforced by injunction". First Opp'n at 7 (citing 18 U.S.C. 3771(a)(1), (a)(5), (d)). But, as defendant BOP points out, the relief plaintiff requests does not implicate any of the rights enumerated under 3771 (footnote 1; see original). BOP Reply at 3; see also Order, Sept. 29, 2011, ECF No. 49 (the court denied plaintiff's September 19, 201 Motion to Enforce Rights Under Crime Victims Rights Act, finding plaintiff failed to demonstrate that he is entitled to relief under 18 U.S.C. 3771). At a maximum, 3771 would only entitle plaintiff to "[t]he reasonable right to confer with the attorney for the Governemnt in [a] case" against his attackers, but would not entitle plaintiff to an injunction compelling BOP to fully debrief him and forward that information to the FBI. See 28 U.S.C. 3771(a)(5). This court has no jurisdiction to direct criminal investigations by the Executive branch.

Accordingly, because plaintiff has identified no legal basis for any of the requested injunctive relief, he is not entitled to such relief. Plaintiff's request for injunctive relief should be stricken from the FAC. And because the striking of plaintiff's requests for declaratory and injunctive relief will leave plaintiff without any claims against BOP, defendant BOP should be dismissed.

B. Defendants McFadden and Norwood Should Not Be Dismissed at this Juncture

Defendants McFadden and Norwood contend that - aside from alleging they had general knowledge of gang activity at USP Victorville - plaintiff fails to allege they had any knowledge that plaintiff would be assaulted and therefore fails to state an Eighth Amendment claim against them for failure to protect. M&N Mot. at 6-7. In addition, they contend that because plaintiff fails to allege facts showing they violated his Eighth Amendment rights that were clearly established in the specific context of this case, they are entitled to qualified immunity. Id. Having duly reviewed the factual allegations, the court disagrees that dismissal of defendants McFadden and Norwood is warranted at this juncture.

1. The FAC Sufficiently States an Eighth Amendment Claim Against Defendants McFadden and Norwood for Failure to Protect

To state a claim against a prison official for violations of the Eighth Amendment based on the failure to protect an inmate from harm, the inmate must show that the official was deliberately indifferent to the inmate's safety. Farmer v. Brennan, 511 U.S. 825, 834, 847, 114 S. Ct. 1970, 128 L. Ed. 2d 811 (1994). To demonstrate that a prison official was deliberately indifferent to a serious threat to the inmate's safety, the prisoner must show that "the official [knew] of and disregard[ed] an excessive risk to inmate... safety; the official must both be aware of facts from which the inference could be drawn that a substantial risk of serious harm exists, and [the official] must also draw the inference". Id. at 837. Moreover, even when an official knows of a substantial risk to inmate health and safety, that official does not violate the Eighth Amendment if he or she responded reasonably to the risk, "even if the harm ultimately was not averted". Id. at 844.

Here, plaintiff alleges that he was termed a "snitch" by other inmates for cooperating with authorities and testifying against another inmate. FAC at 7. Before being transferred to USP Victorville, plaintiff engaged in certain gang activity as "punishment" for snitching on another inmate. Id. at 8. Plaintiff "attempted to leave his gang by seeking protection via the Administrative Remedy Program" and was later transferred to USP Victorville on February 14, 2008. Id. At USP Victorville, plaintiff continued to seek protection and filed administrative remedies about the conditions at USP Victorville. Id. at 10. An administrative response, discussing plaintiff's sexuality and desire for protection, was relayed from defendant Prieto to the Mexican Mafia. Id. The Mexican Mafia ordered an assault on plaintiff, which later occurred in a cell and caused bruises and swelling to plaintiff's face. Id. According to plaintiff, "[f]ollowing each gang related assault, murder or event, [defendants] Norwood and McFadden were notified of the details and identities of [the] participants". Id at 8. In addition, "[d]efendants Norwood and McFadden were responsible for supervising and training sraff, reviewing security plans or procedures, directing their preparation and/or modification, evaluation progress and effectiveness of plans or procedures at USP Victorville". Id.

Following the assault, plaintiff was interviewed and his injuries were photographed. FAC at 10. Also, defendant Norwood personally observed plaintiff's injuries but refused to protect plaintiff. Id. Shortly thereafter, the Mexican Mafia ordered plaintiff killed. Id. On April 9, 2008, five inmates armed with shanks entered plaintiff's cell and attempted to kill him. Id. at 11. Plaintiff sustained severe injuries, including stab wounds and broken bones. Id.

Based upon these factual allegations, the court could reasonably infer that defendants McFadden and Norwood knew of and disregarded the substantial risk that the Mexican Mafia would further assault plaintiff, given plaintiff had already been assaulted by members or associates of the Mexican Mafia for his "sexuality and desire for protection". See Starr, 652 at 1216. Moreover, given the gravity of the situation, the court may fairly infer from the facts alleged that defendants McFadden and Norwood exhibited deliberate indifference by their alleged nonfeasance. Although the factual allegations are not as specific as might be desired with respect to exactly what defendants Norwood and McFadden knew, given the liberal construction of the FAC to which plaintiff is entitled (see Ferdik, 963 F.2d at 1261), they are sufficient at this stage.

Accordingly, the court finds that plaintiff sufficiently states an Eighth Amendment claim against defendants McFadden and Norwood for failure to protect.

2. Defendants McFadden and Norwood Are Not Entitled to Qualified Immunity Based on the Facts Alleged in the FAC

"The doctrine of qualified immunity protects government officials 'from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known'". Pearson v. Callahan, 555, U.S. 223, 231, 129 S. Ct. 808, 172 L. Ed. 2d 565 (2009) (citation omitted). The qualified immunity standard "provides ample protection to all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law". Malley v. Briggs, 475 U.S. 335, 341, 106 S. Ct. 1092, 89 L. Ed. 2d 271 (1986).

In determining whether a public official is entitled to qualified immunity, the court employs a two-step inquiry: (1) whether the facts alleged show the officer's conduct violated a constitutional right; and (2) whether the right was clearly established. See Saucier v. Katz, 533 U.S. 194, 201, 121 S. Ct. 2151, 150 L. Ed. 2d 272 (2001), overruled in part on other grounds by Pearson, 555 U.S. at 236. The two-step inquiry, however, need not be resolved in sequence; rather, the court may exercise its discretion in deciding which of the two-step inquiry should be addressed first. Pearson, 555 U.S. at 236. If a plaintiff satisfies both prongs by demonstrating that the officer violated his clearly established constitutional right, then the officer is not entitled to qualified immunity. Foster v. Runnels, 554 F.3d 807, 810 (9th Cir. 2009). To determine whether a constitutional right was clearly established, the court considers "whether it would be clear to a reasonable officer that his conduct was unlawful in the situation he confronted". Ford v. Ramirez-Palmer, 301 F.3d 1043, 1050 (9th. Cir. 2002) (internal quotation marks and citation omitted); see also Saucier, 533 U.S. at 201 (the determination of whether the law was clearly established "must be undertaken in light of the specific context of the case"). Raising a qualified immunity defense in a motion to dismiss should be done with caution because it places the court in the difficult position of deciding "far-reaching constitutional questions on a nonexistent factual record". Kwai Fun Wong v. United States, 373 F.3d 952, 956-7 (9th Cir. 2004).

Here, as set forth above, "[t]aken in the light most favorable to the party asserting the injury", the facts are sufficient to establish that the conduct of defendants McFadden and Norwood violated plaintiff's constitutional rights under the Eighth Amendment. See Saucier, 533 U.S. at 201; supra Part IV.B.1. Further, at the time of defendants' alleged unconstitutional conduct (deliberate indifference to plaintiff's safety) in 2008, the law regarding a prison official's deliberate indifference to an inmate's safety had long been clearly established. See, e.g., Farmer, 51 U.S. at 833-34. Particularly, it was clearly established that "prison officials have a duty... to protect prisoners from violence at the hands of other prisoners". Farmer, 511 U.S. at 833 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted). Once a prison official becomes subjectively aware of an excessive risk of harm to an inmate's safety, the official violates the inmate's Eighth Amendment rights if he disregards that risk. Id. at 837; see also Berg v. Kincheloe, 794 F.2d 457, 459 (9th Cir. 1986) (a prison official need not "believe to a moral certainty that one inmate intends to attack another at a given place at a time certain before that officer is obligated to take steps to prevent such an assault" (internal quotation marks and citation omitted)).

Defendants may be able to show entitlement to qualified immunity once the record is further developed. But based just on the facts alleged in FAC, defendants McFadden and Norwood are not entitled to qualified immunity.

V.

RECOMMENDATION

IT IS THEREFORE RECOMMENDED that the District Court issue an Order: (1) approving and accepting this Report and Recommendation; (2) granting defendant BOP's Motion to Dismiss, dismissing BOP and striking plaintiff's requests for declaratory and injunctive relief from the FAC; and (3) denying defendants McFadden's and Norwood's Motion to Dismiss.

Dated: July 2, 2012

SHERI PYM

UNITED STATES MAGISTRATE JUDGE

Other posts by this author

|

2014 mar 11

|

2014 mar 11

|

2014 mar 7

|

2014 mar 7

|

2013 nov 14

|

2013 nov 11

|

More... |

Replies (1)