Transcription

#9

11.11.18

Reply: ffgy

Okay Cal,

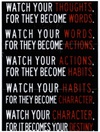

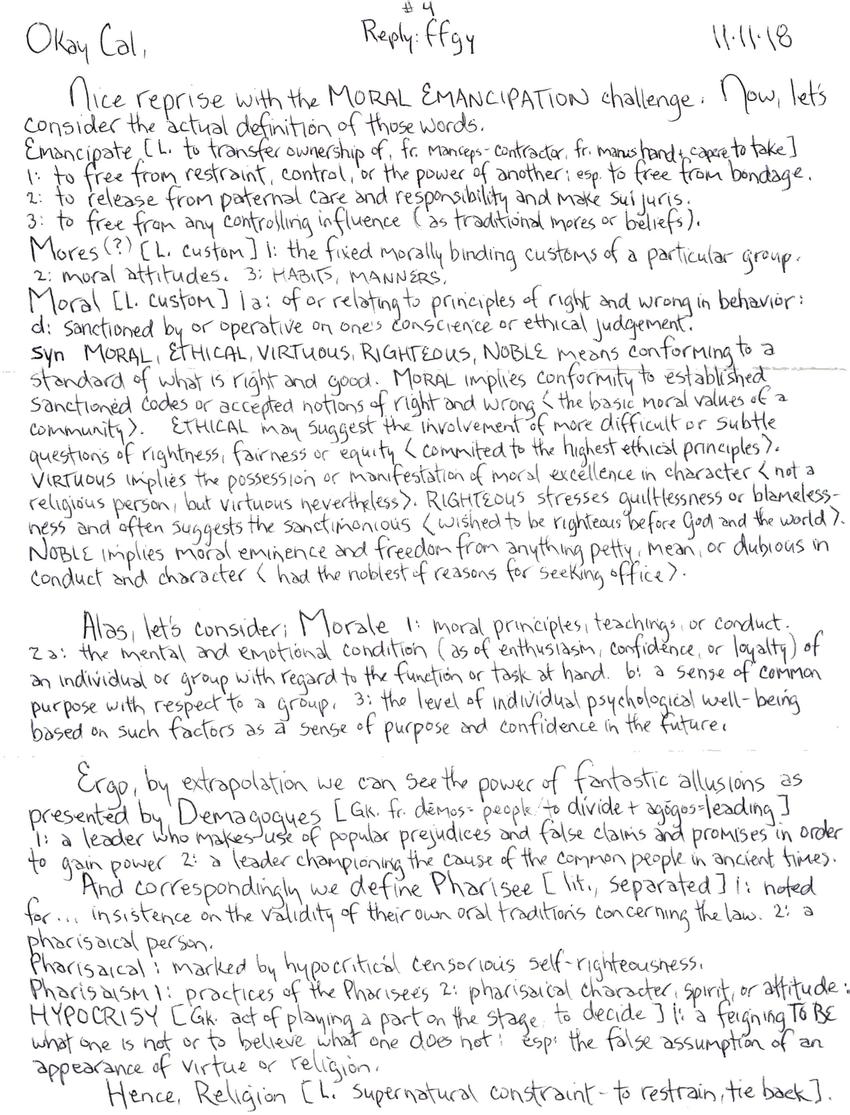

Nice reprise with the MORAL EMANCIPATION challenge. Now, let's consider the actual definition of those words.

Emancipate [L. to transfer owership of, fr. manceps - contractor, fr. manustand + capere to take]

1: to free from restraint, control, or the power of another: esp. to free from bondage.

2: to release from paternal care and responsibility and make sui juris.

3: to free from any controlling influence (as traditional mores or beliefs).

Mores (?) [L. custom] 1: the fixed morally binding customs of a particular group.

2: moral attitudes. 3: Habits, manners.

Moral [L. custom] 1a: of or relating to principles of right and wrong in behavior: d: sanctioned by or operative on one's conscience or ethical judgement. syn MORAL, ETHICAL, VIRTUOUS, RIGHTEOUS, NOBLE means conforming to a standard of what is right and good. MORAL implies conformity to established sanctioned codes or accepted notions of right and wrong (the basic moral values of a community). ETHICAL may suggest the involvement of more difficult or subtle questions of rightness, fairness or equity (committed to the highest ethical principles). VIRTUOUS implies the possession or manifestation of moral excellence in character <not a religious person, but virtuous nevertheless>. RIGHTEOUS stresses guiltlessness or blamelessness and often suggests the sanctimonious <wished to be righteous before God and the world>. NOBLE implies moral eminence and freedom from anything petty, mean, or dubious in conduct and character <had the noblest of reasons for seeking office>.

Alas, let's consider: Morale 1: moral principles, teachings, or conduct. 2a: the mental and emotional condition (as of enthusiasm, confidence, or loyalty) of an individual or group with regard to the function or task at hand. b: a sense of common purpose with respect to a group. 3: the level of individual psychological well-being based on such factors as a sense of purpose and confidence in the future.

Ergo, by extrapolation we can see the power of fantastic allusions as presented by demagogues [Gk. fr. demos = people/to divide + agogos = leading] 1: a leader who makes use of popular prejudices and false claims and promises in order to gain power 2: a leader championing the cause of the common people in ancient times.

And correspondingly we define Pharisee [lit., separated] 1: noted for... insistence on the validity of their own oral traditions concerning the law. 2: pharisaical person.

Pharisaical: marked by hypocritical censorious self-righteousness.

Pharisaism 1: practices of the Pharisees 2: pharisaical character, spirit or attitude: HYPOCRISY [Gk. act of playing a part on the stage, to decide] 1: a feigning to be what one is not or to believe what one does not: esp. the false assumption of an appearance of virtue or religion.

Hence, religion {L. supernatural constraint - to restrain, tie back]

Other posts by this author

|

2023 may 31

|

2023 apr 5

|

2023 mar 19

|

2023 mar 5

|

2023 mar 5

|

2023 mar 5

|

More... |

Replies (11)

Hey William,

Thank you for your kind and meaningful compliment: “Nice reprise with the MORAL EMANCIPATION challenge.” I think you raise deep questions that most humans underthink.

I appreciate your examination and derivation of concepts like “moral”, “Pharisee”, and “religion”. I think I better understand what you’re getting at. I want to comment a little bit on your response, as well as raise a few questions that I find interesting.

First, I like your distinction between “moral” and “ethical”. Unless I have a misunderstanding, you seem to be making the following distinction: Morals deal with conformity to socially accepted or institutionally established standards, whereas ethics deal with rightness, fairness, or equity. What do you think is the precise relationship between morals and ethics? You suggest that there is at least a difference in difficulty: “ETHICAL may suggest the involvement of more difficult or subtle questions…” Is there also a difference in kind? To what extent do ethics and morals deal with the same subject matter, if at all?

Second, I think you’re right about the connection between virtue and morality. Being virtuous is possessing a set of human excellences. The philosopher Aristotle would wholeheartedly agree. You specifically mention that being virtuous involves “moral excellences in character”. I have for you a question that I find interesting: Do you think that being virtuous involves not just moral excellences in character, but also intellectual excellences? Is being able to do calculus, for example, a virtuous excellence? I’m not so sure what the answer is. Perhaps intellectual excellences are just a certain kind of moral excellences in character. Here is another question that I find interesting: How do ethical excellences differ from moral excellences, if at all? The answer seems to depend on what difference, if any, there holds between ethics and morals.

I also agree that righteousness suggests the sanctimonious. The concept of righteousness often shows up in religious and theological thought, for example. I often wonder about the connections between righteousness and virtue. It seems that being righteous is enough for being minimally virtuous. If a person substantially lacks virtue, then she is somehow guilty or blameworthy, and hence unrighteous. But is being righteous enough for possessing all or most of the virtues? Can someone be righteous but nevertheless lack many crucial virtues? Your comments on Pharisees may shed light on the matter.

You note the connection between being pharisaical and being self-righteous. As it seems, being pharisaical is incompatible with being perfectly virtuous or ethical, since it involves the vice of self-righteousness. Here is a question for you, William: What is the precise relationship between righteousness and self-righteousness? Is self-righteousness a form of righteousness? Or is self-righteousness incompatible with righteousness? On the one hand, the name “self-righteous” suggests righteousness. On the other hand, self-righteousness is a blameworthy defect, whereas righteousness is often considered a perfectly praiseworthy state.

I liked your side-by-side definitions of “demagogue” and “Pharisee”. Defining these concepts side-by-side helped me better understand their connections and potential differences. Have you ever met anybody whom you considered both a demagogue and a Pharisee? Whom in history do you consider an example of both a demagogue and Pharisee? Whom do you consider a demagogue but not a Pharisee? A Pharisee but not a demagogue? Or would you argue that all demagogues are Pharisees, or vice versa?

Alright, that’s all for now, William. As always, it’s a pleasure to discuss these stimulating and vital issues with you. Take care, and good luck on your further intellectual and spiritual endeavors.

Peace,

Calhoun25

As always, I am glad to hear back from you!

I did have the pleasure of looking at some of your NSOL coursework. I enjoyed reading the questions and answers, which deal with an impressively diverse range of topics. I found Question #87 especially interesting: “How can a person determine if an act is good or bad?” You proceed to state a necessary condition on good acts: “To be good, something must contribute to the individual to his family, his children, his group, mankind or life. Acts are good which are more beneficial than destructive along these dynamics.” I find this a very respectable and plausible position, one that many philosophers have espoused in one form or another. I am interested in querying your intuitions about a famous test case in philosophy. This a case where an act may appear good, even though it does not generate more benefits than harms—indeed, it seems to create more harms than benefits. Here it is:

Promise Case. Your friend has asked you to hold his $50. Friday after work, he asks you for his money back. You know he will use the money for getting drunk, which is very unhealthy for him. Should you give your friend his money back?

Some thinkers have the intuition that you should give back the money, since your friend has a strong right to it. They believe that giving back the money is a good or right act, even though it generates more harms than benefits. The assumption is that respecting your friend’s rights does not, in itself, count as a benefit for him. What do you think about this case? Do you think that giving back the money is a good act? Should we count respecting rights as an intrinsic benefit, apart from any benefits it might lead to?

Compensation Case. Anne is now retired. She served fifty years as a just and distinguished policewoman. For her civic contribution, Anne received a generous pension fund from the local government. One day, some crooked schemers cheat Anne out of her retirement funds. Anne lost all her money, and through no fault of her own. The local government is deciding whether to pay her a new pension. They could use some rainy day funds to pay Anne or to build a recreation center for the community. Only one of the two options is financially possible, and the second option will undoubtedly generate more good than the first option. What should the local government do?

Some thinkers have the intuition that the local government should pay Anne, even though doing so would not create the greatest good for the greatest number. Anne deserves and has a strong right to retirement funds from the government, given her exemplary civic service. What do you think about this case? Can an act be good or right, even when it does not maximize benefits?

I find your distinction between ethics and morality fascinating. Sometimes people use the terms “ethics” and “morality” interchangeably, but you are using them to draw an insightful distinction between two concepts. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has an interesting article on defining morality. It notes that “morality” may have one of two different senses: (one) a descriptive sense, and (two) a normative sense. According to the descriptive sense, the term “morality” refers to a certain code of conduct put forward by a society or a group. This sounds more like your definition of morality. According to the normative sense, the term “morality” refers to a certain code that all rational persons, under certain specified conditions, would endorse. This sense mentions a connection with rationality, and it somewhat reminds me of your definition of ethics. However, your definition is unique in that it talks about “self-determined” rationality, as opposed to rationality simpliciter. Would you say there is a “group” rationality? Would that be what you call “suppressive reasonableness” and “double mindedness”? Could it turn out that all rationality is “self-determined”?

I am so happy to hear about Destiny’s post and how it made you feel. I was trying to find her post, but I was unable to. I must have been looking at the wrong blog posts. Anyway, it is intriguing that she distinguishes knowledge from wisdom. Some philosophers make a distinction between knowledge and understanding, so a distinction between knowledge and wisdom makes perfect sense.

Discussing these questions with you has helped me better understand the concepts of righteousness, self-righteousness, and virtue. Your thoughts seem to line up with a certain aspect of natural law theory. According to natural law theorists, every human being, insofar as they are properly functioning, has a reasoning capacity that allows them to know general truths about right and wrong. A properly functioning human can know, by the very light of natural reason, that stealing from old ladies is wrong. Of course, pernicious habits or incorrect teachings can interfere with or degrade our natural reason. But insofar as it works, our natural reason allows us access to general ethical truths. I suppose natural law theorists would agree that intellectual virtues matter ethically, since a sharpened ability to reason can better lead us to general truths about right and wrong. Other thinkers disagree with natural law theorists. They think it is our emotions—not our natural reasoning abilities—that guide us to general ethical truths. Still others believe there are no general ethical truths; or if there are, human beings can have no knowledge of them.

Alright, that’s all for now, William. I’ll talk to you later. I hope it starts warming up soon. I have some friends in Chicago who had a brutal time with the weather. As you may have heard, it got down to negative fifty degrees Fahrenheit there, when you factor in the wind chill. Ouch!

Peace,

Calhoun25

Hey William,

It's a joy to read your latest letter!

I like your response to the $50 case. It's an interesting solution! Set the ground rules beforehand, and let those rules comprise the moral boundaries. "I'll hold your money and return it on request, only if you agree to an early withdrawal fee." The morally right actions are only those in keeping with your agreement.

Perhaps we humans underuse promises and contracts as a way to set moral constraints in advance. (We certainly misuse them!) A solid agreement can often prevent moral dilemmas from ever even arising. Maybe we humans fail to capitalize on this potential value.

Speaking of agreements, I want to mention social contract theory. Some of its famous proponents include Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, and--most recently--John Rawls. You might (or might not) be a fan of social contract theory. Here is its core idea: Widespread or universal social agreement can justify certain social arrangements. Just as individual contracts can sometimes justify individual arrangements, a social contract can sometimes justify social arrangements. For example, if society has widespread or universal agreement on instituting some tax, then it can justly do so, at least under normal circumstances.

Some thinkers disagree with social contract theory. They claim that social agreement cannot, in itself, justify social arrangements. It is something else that justifies certain social arrangements--for example, the fact that those arrangements would generate the greatest good. It seems like you might agree with this objection in some form or another.

I appreciate your clarification of "survival". I like that your concept is expansive and rich. It signifies a wholeness in life: "To Flourish and Prosper mentally, spiritually, personally, socially, ecologically, universally". Not enough people live their lives with the explicit, conscious aim of "survival", although perhaps everybody implicitly strives for it.

Your concept of survival reminds me of the Jewish concept of shalom. The author Cornelius Plantinga, brother to the famous philosopher Alvin Plantinga, powerfully explains what shalom is: "The webbing together of God, humans, and all creation in justice, fulfillment, and delight is what the Hebrew prophets call shalom. We call it peace but it means far more than mere peace of mind or a cease-fire between enemies. In the Bible, shalom means universal flourishing, wholeness and delight – a rich state of affairs in which natural needs are satisfied and natural gifts fruitfully employed, a state of affairs that inspires joyful wonder as its Creator and Savior opens doors and welcomes the creatures in whom he delights. Shalom, in other words, is the way things ought to be." As you say about "survival", shalom is about "homosapiens [being] the best they can be".

Unfortunately, as things stand, the world is far from shalom. It is shattered, as evidenced by the atrocities you mention: Indigenous Americans being deprived of their land, Africans being forced into slavery, and defendants being wrongly accused or poorly represented. We humans regularly fail to give others their proper due, and often in gastly ways. However we respond to being treated unjustly, it still stands that we were treated unjustly, at least as a historical fact.

That said, how we respond can be vital for our personal well-being and moral character. You mention "learning from experience" as the only rational response to being treated unjustly. That is an interesting position! I agree that education is sometimes the most rational response. But would you ever consider reaction--i.e. trying to change "external" conditions--as rational? For example, would you ever judge organizing against unjust working conditions as rational? Another way to put the point: How passive (or active) is "learning from experience" for you? I understand that education is often very active. But would you count trying to change "external" conditions as education? ("External" conditions include how others think and behave, how impersonal systems operate, and how nature operates absent human intervention.)

I think you're spot on that "Lady Justice is blindfolded for a reason". Reality involves so many competing claims to justice. How ought we to arbitrate between them? Society has only so many resources, and sometimes it is impossible to satisfy all claims to justice. Just consider these three kinds of injustice: Unfair healthcare practices, unfair police practices, and unfair housing practices. How much should society focus on each one? It cannot give 100% of itself to all of them. I often worry how to balance competing claims of justice. As I've heard, there are smart thinkers who try their best on these problems. I wonder whether they've found any interesting solutions. At any rate, it might be too difficult for society to focus on rectifying injustice, since government officials are not "held to the highest level of scrutiny", as you write.

Hmm, your parting question is a deep one: "What do you think you'd Do, Be, Have [after escaping exile]???" (I really like your allusion to Homer's Odyssey.) I'm not sure how helpful my answer would be, since I have difficulty imagining such a long exile. Nevertheless, I'll try my best. I suppose the first thing I'd do is try to get established. I know each state has its own prison reentry programs. I'm not sure which ones are good, but hopefully at least some are. I'd check with a social worker for these programs, or perhaps check the internet. (The website https://helpforfelons.org/reentry-programs-ex-offenders-state/ lists reentry programs by state.) I'd probably be happy with a simple job, even if it weren't amazing, because I'd primarily be interested in trying new things. Visiting national parks, such as Shenandoah or Grand Teton National Park, would be exciting. Joining new clubs with new people would also be engaging. I hope my thoughts are somewhat helpful, or at least not unhelpful.

Alright, that's all for now, William. I'd enjoy reading your next response, should you write one. With your Odysseus reference in mind, I am tempted to label your responses as "travel logs". Anyway, take care, good luck, and--again, with the Odysseus reference in mind--bon voyage!

Shabbat Shalom,

Calhoun25