Transcription

5/21/2020

The Company Store | Prison Policy Initiative

PRISON POLICY INITIATIVE

The Company Store:

A Deeper Look at Prison Commissaries

By Stephen Raher

May 2018

Press release

Prison commissaries are an essential but unexamined part of prison life. Serving as the core of the prison retail market, commissaries present yet another opportunity for prisons to shift the costs of incarceration to incarcerated people and their families, often enriching private companies in the process. In some contexts, the financial exploitation of incarcerated people is obvious, evidenced by the outrageous prices charged for simple services like phone calls and email. When it comes to prison commissaries, however, the prices themselves are not the problem so much as forcing incarcerated people — and by extension, their families — to pay for basic necessities.

Understanding commissary systems can be daunting. Prisons are unusual retail settings, data are hard to find, and it’s hard to say how commissaries “should” ideally operate. As the prison retail landscape expands to include digital services like messaging and games, it becomes even more difficult and more important for policymakers and advocates to evaluate the pricing, offerings, and management of prison commissary systems.

The current study

To bring some clarity to this bread-and-butter issue for incarcerated people, we analyzed commissary sales reports from state prison systems in Illinois, Massachusetts, and Washington. We chose these states because we were able to easily obtain commissary data, but conveniently, these three states also represent a decent cross section of prison systems, encompassing a variety of sizes and different types of commissary management.

We found that incarcerated people in these states spent more on commissary than our previous research suggested, and most of that money goes to food and hygiene products. We also discovered that even in state-operated commissary systems, private commissary contractors are positioned to profit, blurring the line between state and private control.

Lastly, commissary prices represent a significant financial burden for people in prison, even when they are comparable to those found in the "free world." Yet despite charging seemingly "reasonable" prices, prison retailers are able to remain profitable, which raises serious concerns about new digital products sold at prices far in excess of market rates.

How much do incarcerated people spend in the commissary?

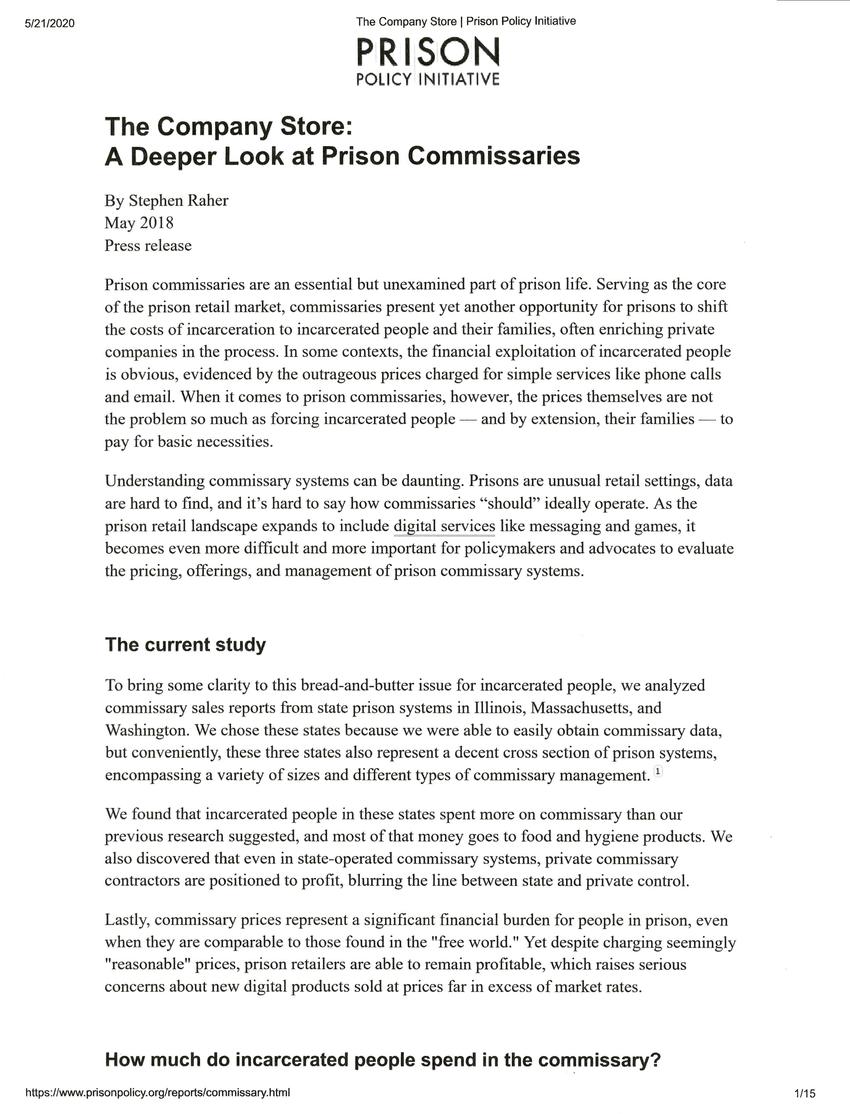

In Illinois and Massachusetts, incarcerated people spent an average of over $1,000 per person at the commissary during the course of a year. Annual per capita sales in Washington were about half as much.

Table 1. Incarcerated people spent an average of $947 per person, per year, in the three sampled states. Spending did not seem to vary based on whether the commissary operator was private (as in Massachusetts) or state-run (in Illinois and Washington). See Footnote 2 and Footnote 4 for details about the data sources.

Illinois Massachusetts Washington Average

Annual Commissary Sales $48,416,118 $11,713,446 $8,696,721

Avg Daily Prison Pop 43,199 9,703 16,943

Per-person Annual Sales $1,121 $1,207 $513 $947

Commissary operator State DOC Contractor (Keefe) State DOC

Per-person commissary sales for the three sampled states amounted to $947, well over the typical amount incarcerated people earn working regular prison jobs in these states ($180 to $660 per year). The per-person sales were also higher than a previous survey had suggested. In 2016, we estimated that prison and jail commissary sales amount to $1.6 billion per year nationwide, based in part on data from a 34-state survey by the Association of State Correctional Administrators. But the more recent and more detailed data presented in this report suggest that commissary might be an even higher-grossing industry than we previously thought.

There were important state differences in commissary sales, however. Washington’s per-person average was dramatically lower than the other two states’. The reason for this difference isn’t entirely clear, but it seems that personal property policies issued by the Department of Corrections are at least partially responsible for this significant disparity.

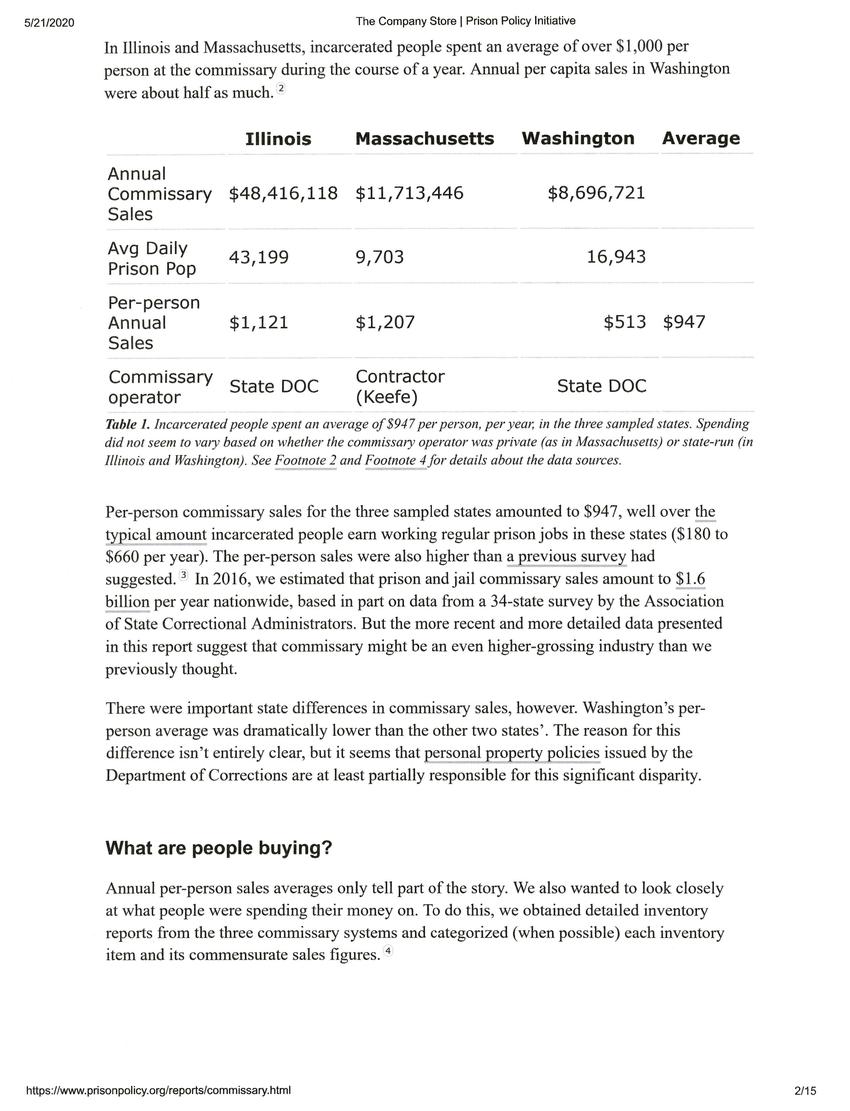

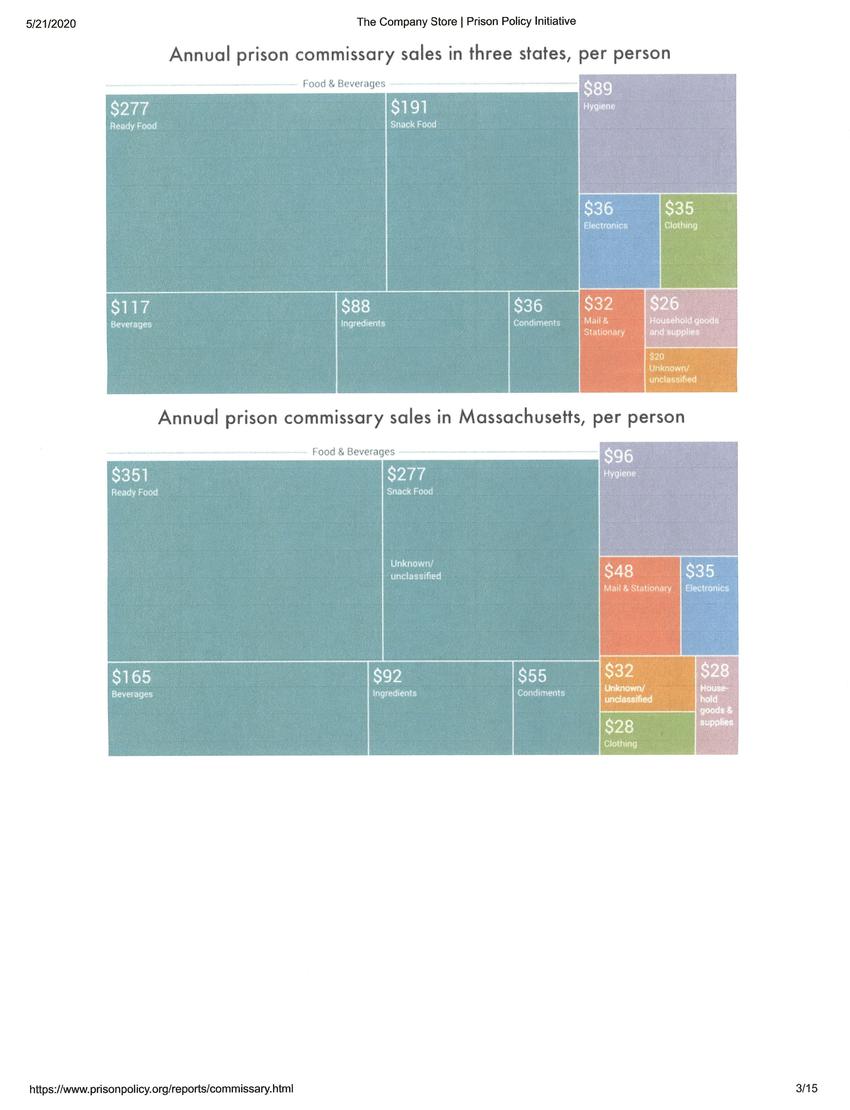

What are people buying?

Annual per-person sales averages only tell part of the story. We also wanted to look closely at what people were spending their money on. To do this, we obtained detailed inventory reports from the three commissary systems and categorized (when possible) each inventory item and its commensurate sales figures.

Annual prison commissary sales in three states, per person

[chart]

Annual prison commissary sales in Massachusetts, per person

[chart]

Annual prison commissary sales in Illinois, per person

[chart]

Annual prison commissary sales in Washington, per person

[chart]

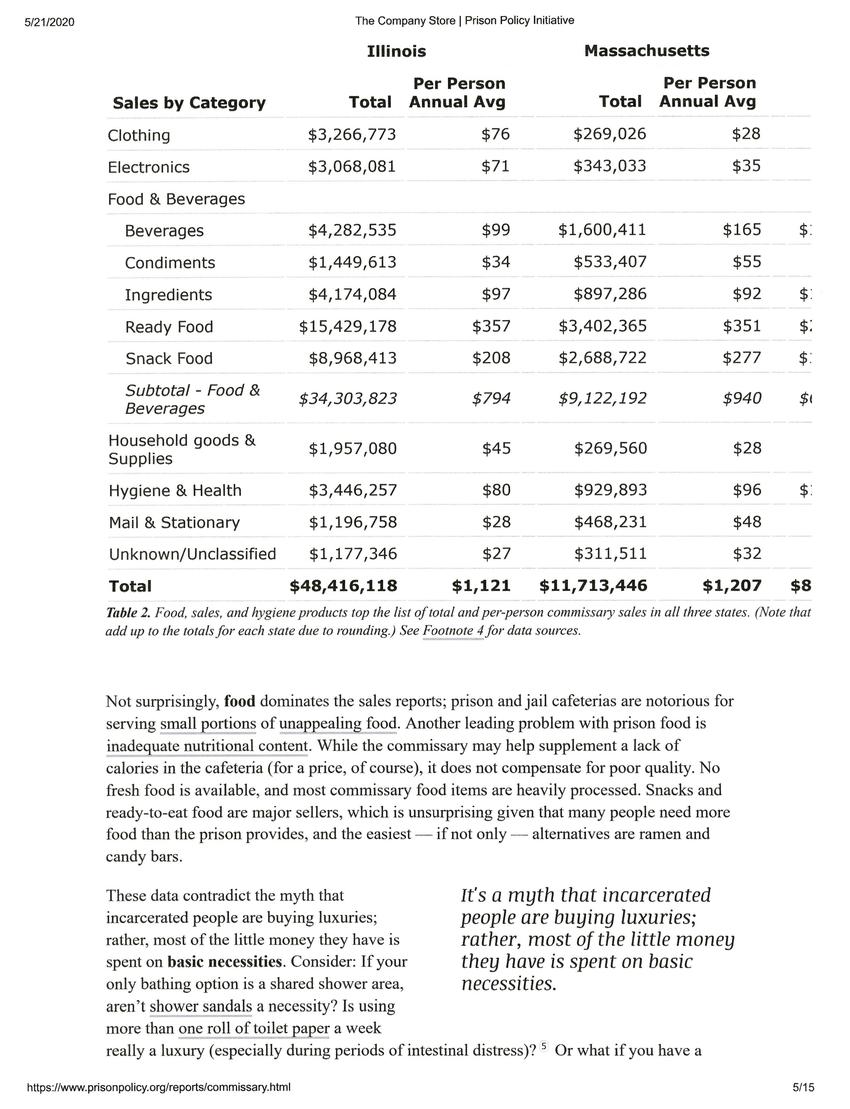

Illinois Massachusetts Washington

Sales by Category Total Per Person Annual Avg Total Per Person Annual Avg Total Per Person Annual Avg

Clothing $3,266,773 $76 $269,026 $28 $20,131 $1

Electronics $3,068,081 $71 $343,033 $35 $15,011 $1

Food & Beverages

Beverages $4,282,535 $99 $1,600,411 $165 $1,492,599 $88

Condiments $1,449,613 $34 $533,407 $55 $338,344 $20

Ingredients $4,174,084 $97 $897,286 $92 $1,273,352 $75

Ready Food $15,429,178 $357 $3,402,365 $351 $2,102,377 $124

Snack Food $8,968,413 $208 $2,688,722 $277 $1,466,314 $87

Subtotal - Food & Beverages $34,303,823 $794 $9,122,192 $940 $6,672,986 $394

Household goods & Supplies $1,957,080 $45 $269,560 $28 $95,236 $6

Hygiene & Health $3,446,257 $80 $929,893 $96 $1,547,409 $91

Mail & Stationary $1,196,758 $28 $468,231 $48 $345,947 $20

Unknown/Unclassified $1,177,346 $27 $311,511 $32 $0 $0

Total $48,416,118 $1,121 $11,713,446 $1,207 $8,696,721 $513

Table 2. Food, sales, and hygiene products top the list of total and per-person commissary sales in all three states. (Note that the subtotals in this table do not add up to the totals for each state due to rounding.) See Footnote 4 for data sources.

Not surprisingly, food dominates the sales reports; prison and jail cafeterias are notorious for serving small portions of unappealing food. Another leading problem with prison food is inadequate nutritional content. While the commissary may help supplement a lack of calories in the cafeteria (for a price, of course), it does not compensate for poor quality. No fresh food is available, and most commissary food items are heavily processed. Snacks and ready-to-eat food are major sellers, which is unsurprising given that many people need more food than the prison provides, and the easiest — if not only — alternatives are ramen and candy bars.

It's a myth that incarcerated people are buying luxuries; rather, most of the little money they have is spent on basic necessities.

These data contradict the myth that incarcerated people are buying luxuries; rather, most of the little money they have is spent on basic necessities. Consider: If your only bathing option is a shared shower area, aren’t shower sandals a necessity? Is using more than one roll of toilet paper a week really a luxury (especially during periods of intestinal distress)? Or what if you have a chronic medical condition that requires ongoing use of over-the-counter remedies (e.g., antacid tablets, vitamins, hemorrhoid ointment, antihistamine, or eye drops)? All of these items are typically only available in the commissary, and only for those who can afford to pay.

Bringing this discussion into the realm of the concrete, consider the following examples from Massachusetts. In FY 2016, people in Massachusetts prisons purchased over 245,000 bars of soap, at a total cost of $215,057. That means individuals paid an average of $22 each for soap that year, even though DOC policy supposedly entitles them to one free bar of soap per week. Or to take a different example: the commissary sold 139 tubes of antifungal cream. Accounting for gross revenue of just $556, the commissary contractor is obviously not getting rich selling antifungal cream, no matter the mark-up—instead, the point is that it’s hard to imagine why anyone would purchase antifungal cream other than to treat a medical condition. Yet Massachusetts has forced individual commissary customers to pay for their own treatment, at $4 per tube, which can represent four days’ wages for an incarcerated worker.

How do incarcerated people afford commissary?

Policies drive consumption: property ownership and prison pay rates

(expand)

For many people in prison, their meager earnings go right back to the prison commissary, not unlike the sharecroppers and coal miners who were forced to use the “company store.” When their wages are not enough, they must rely on family members to transfer money to their accounts — meaning that families are effectively forced to subsidize the prison system. Others in prison who lack such support systems simply can’t afford the commissary at all.

While the sales data allow us to calculate average commissary expenditures per person using the total prison population, this number does not tell the whole story: It flattens the spending gap between prisoners who can “afford” to buy from the commissary versus those who cannot.

The poorest people in prison, such as those considered “indigent” by the state, spend little to nothing at the commissary. This, in turn, means that the per capita spending for all others is actually greater than the average numbers reported above. We can get a very limited glimpse of this population by looking at Washington, where commissaries stock certain items that are available only to people who qualify as indigent. Based on annual sales of “indigent toothpaste” and “indigent soap,” it appears that a significant portion of people in Washington’s prisons (between about ten percent and one-third) are indigent.

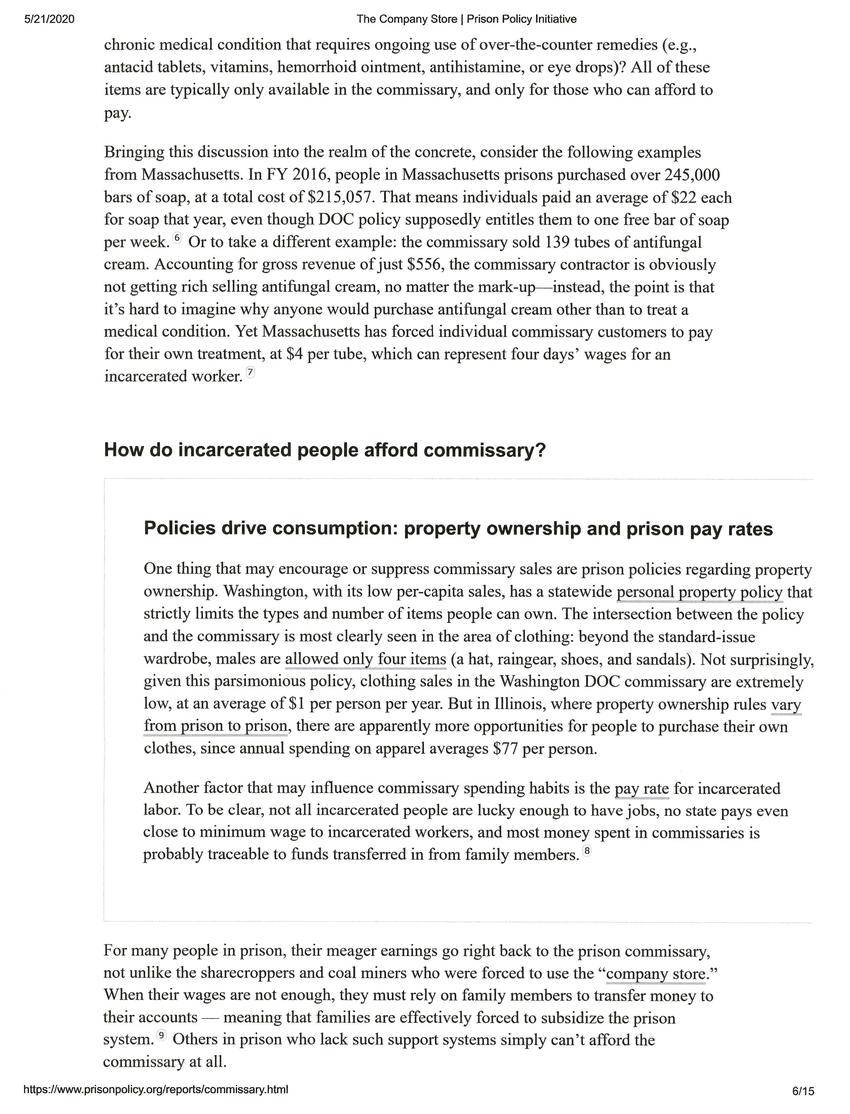

How “fair” are free-world prices in a prison?

[image]

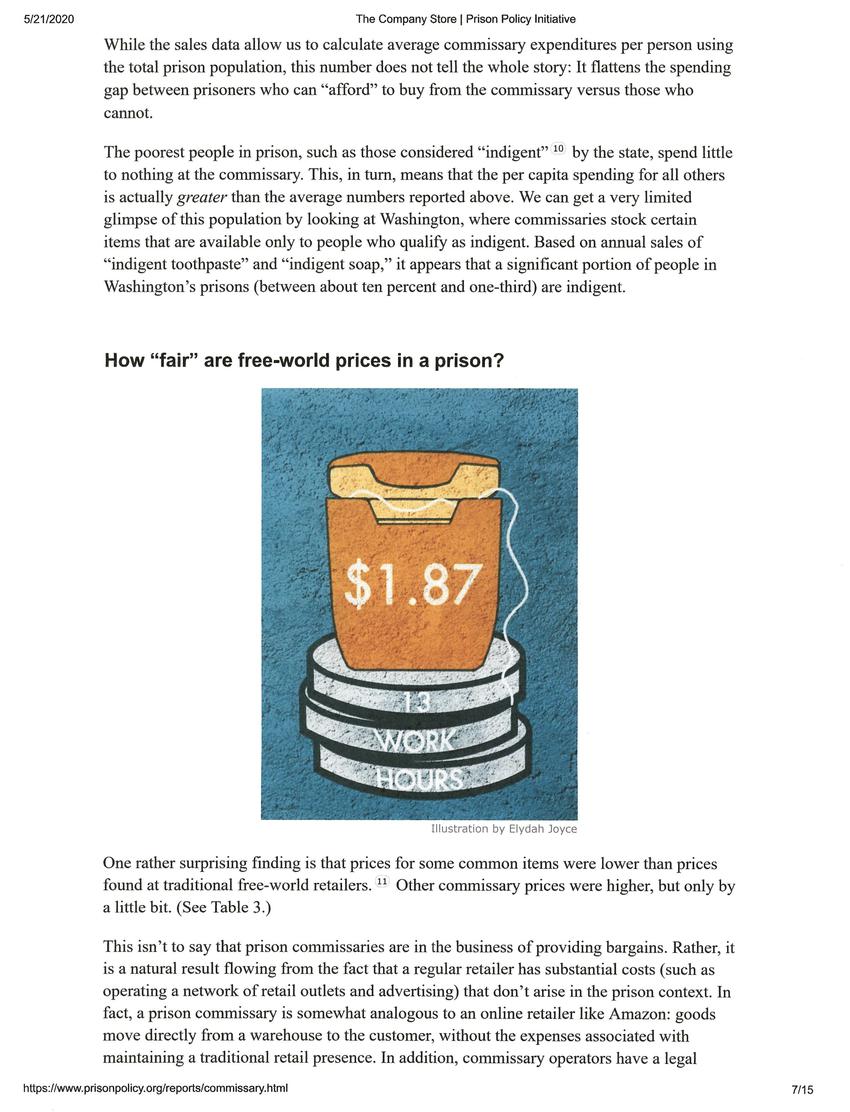

One rather surprising finding is that prices for some common items were lower than prices found at traditional free-world retailers. Other commissary prices were higher, but only by a little bit. (See Table 3.)

This isn’t to say that prison commissaries are in the business of providing bargains. Rather, it is a natural result flowing from the fact that a regular retailer has substantial costs (such as operating a network of retail outlets and advertising) that don’t arise in the prison context. In fact, a prison commissary is somewhat analogous to an online retailer like Amazon: goods move directly from a warehouse to the customer, without the expenses associated with maintaining a traditional retail presence. In addition, commissary operators have a legal monopoly, so they don’t have to worry about price competition, and thus do not incur costs associated with special sales or discounts.

Item Illinois Massachusetts Washington Amazon

Commissary Local Retail Commissary Local Retail Commissary Local Retail

VO5 shampoo

12.5 oz. bottle $1.25 (LIN) to $1.69 (VIE) $0.99 (Jewel, Chicago) $1.38 $1.29 (Star Market, Cambridge) $1.71 (no size specified) $1.19 (Bartell’s Drugstore, Seattle) $4.88

Bic twin razor (single) $0.12 (HIL) to $0.18 (LIN) $0.35 (based on $3.49 for pkg of 10) (Jewel) $0.15 Unable to locate; comparable product (Gillette) available @ $1.20 (based on $11.99/pk of 10) $0.22 $1.20 (based on 5.99 for pkg of 5) (Bartell’s) $0.57 (based on $5.72 for pkg of 10)

Maruchan beef ramen $0.25 (multiple locations) $0.34 (based on $1 for pkg of 3) (Jewel) $0.40 $0.59 (Star Market) $0.25 or $0.29 (no brand specified) $0.89 (IGA Seattle) $0.71 (based on $16.99 for case of 24)

Mrs. Dash

2.5 oz. bottle $2.98 (multiple) to $3.26 (multiple) $2.99 (Jewel) $2.40 $3.49 (Star Market) not available $4.09 (IGA Seattle) $2.94

Table 3. While prices for some items are comparable or even lower than prices found in free-world stores, the costs are significant for incarcerated people and their families. (Note that in Illinois, commissary prices vary by facility, so the abbreviations for facilities charging the lowest and highest prices are given.) See Footnote 4 for data sources.

The other thing to keep in mind when comparing commissary prices to the free world is that people in prison have drastically less money to spend. So, while $1.87 may sound like a fair price to pay for a month’s worth of dental floss, the transaction feels very different from the perspective of someone in a Massachusetts prison who earns 14 cents per hour and has to work over 13 hours to pay off that floss. Or, to consider a different scenario: the average person in the Illinois prison system spends $80 a year on toiletries and hygiene products — an amount that could easily represent almost half of their annual wages.

Privatization can take different forms

When a prison system’s commissary is run by a private company, it raises logical concerns about fairness and coercion. In 2016, when one of the largest prison food service/commissary companies (Trinity Services Group) merged with another dominant commissary company (Keefe Group), we expressed concerns about the concentration of power and diminished competition — and quality — that would result. The passage of time has confirmed these fears: by 2017, maggots, dirt, and mold were reported in meals served by Trinity; these quality problems along with small portions led to multiple prison protests and $3.8 million in fines for contract violations in Michigan alone.

But exploitation can occur even if a system is not fully privatized. Of the three states we examined, only Massachusetts has a contractor-operated commissary system. It also has the highest per-person average commissary spending. It is tempting to conclude that the profit motive of commissary contractors leads to higher mark-ups and thus higher per capita spending, but we would need a larger sample size to test this hypothesis. What is notable in our three-state survey is that Illinois, with its state-run commissary, had per capita sales almost as high as Massachusetts’ contractor-run system, so a state-run system is clearly not a panacea. In addition, per capita spending in Washington and Illinois are so dramatically different that there must be other significant factors beyond outsourcing.

Arguably the most important privatization-related information in this study comes from Illinois. The Illinois prison commissary system has also been subject to harsh criticism for poor purchasing policies. In a 2011 report on commissary shortcomings, the Illinois Procurement Policy Board noted that only nineteen vendors provided 91% of all the items (measured by dollar amount) sold in the commissary. Among this handful of dominant providers, the one with the largest share was none other than Keefe, which accounted for 30% of the commissary’s spending. Thus, if Illinois is any indication, it appears that Keefe is positioned to make money even in states that have not privatized the operation of their prison commissaries.

The future of commissary: digital sales

Incarceration is becoming increasingly expensive — especially for those behind bars and their families. While prisons find new ways to shift the costs of corrections to incarcerated people (think medical co-pays and pay-to-stay fees), vendors are aggressively pushing new digital products that will further monetize incarcerated people.

This new breed of digital sales can take different forms. Sometimes this consists of “free” computer tablets that offer subscription based music streaming or ebooks. Other times, people must buy tablets or MP3 players and then pay for digital content. Given monopoly contracts and a captive market, prison and jail telecommunications providers are able to generate revenues far greater than similar companies in non-prison settings.

Some states appear to separate digital sales from the prison commissary, while others sell music downloads and other digital content through the commissary. Of the three states we looked at, Illinois was the only system that included digital sales in its commissary reports. The Illinois DOC contracts with GTL to provide electronic messaging and, apparently, digital music downloads. We say “apparently” because there is no reference to music downloads on the Illinois DOC website, but based on the sales figures, music sales seem to be a substantial money-maker:

Table 4. Of the three sampled states, only Illinois included sales figures from the emerging market of digital sales in its commissary reports. In that state alone, sales of electronic messages, music, and hardware, such as MP3 players, topped $1 million in 2016-2017.

Description Inventory Item Qty Sold Gross Sales

Electronic messaging Prepaid bundles of 1 or 20 messages 12,443 $35,301

Music Unclear 82,374 $838,947

Hardware MP3 players and accessories 3,171 $267,550

TOTAL $1,141,798

Price-gouging in commissaries is concentrated in the digital realm

[image]

The pricing information discussed earlier provides evidence of an important fact: commissaries can afford to sell goods at prices comparable to or lower than free-world stores even while absorbing extra security-related costs (such as secure warehouses) and reaping healthy corporate profits. It appears prisons are ignoring these advantages when evaluating the prices of new digital products. As a prime example, the Massachusetts DOC signed a new contract with Keefe about a year ago, which includes electronic messaging and MP3

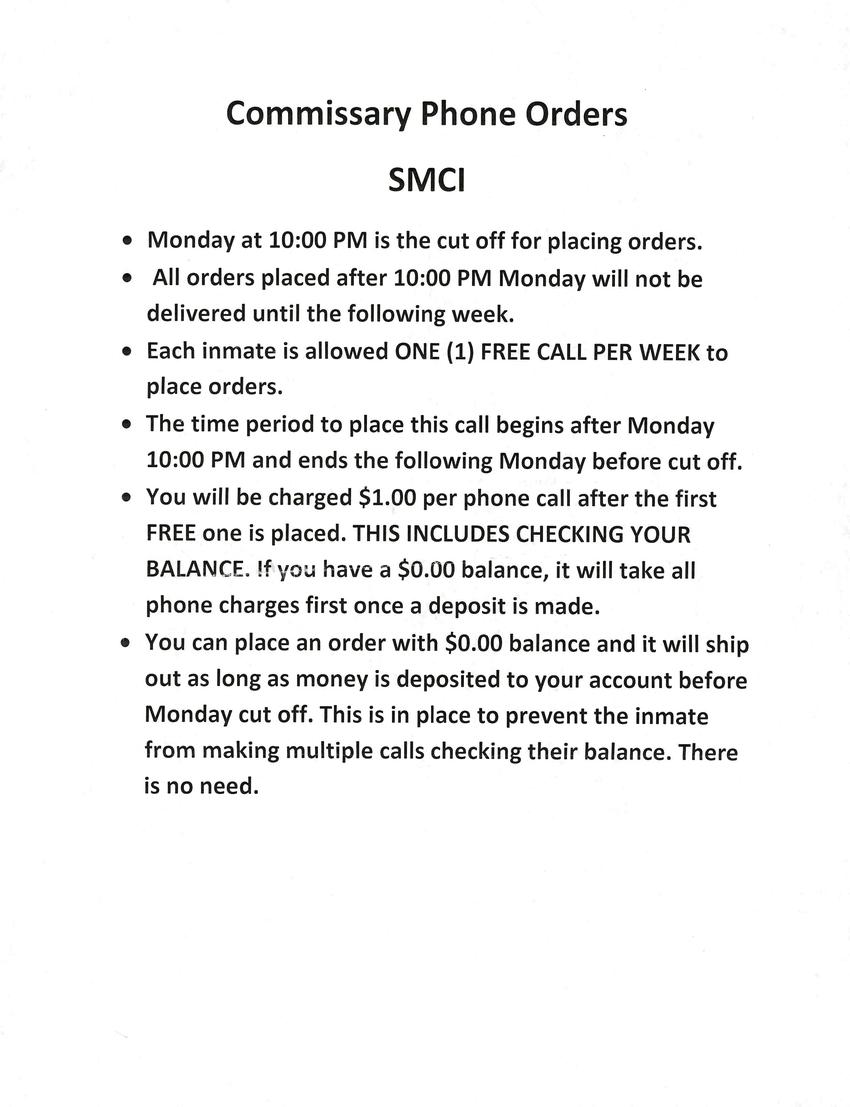

Commissary Phone Orders

SMCI

* Monday at 10:00 PM is the cut off for placing orders.

* All orders placed after 10:00 PM Monday will not be delivered until the following week.

* Each inmate is allowed ONE (1) FREE CALL PER WEEK to place orders.

* The time period to place this call begins after Monday 10:00 PM and ends the following Monday before cut off.

* You will be charged $1.00 per phone call after the first FREE one is placed. THIS INCLUDES CHECKING YOUR BALANCE. If you have a $0.00 balance, it will take all phone charges first once a deposit is made.

* You can place an order with a $0.00 balance and it will ship out as long as money is deposited to your account before Monday cut off. This is in place to prevent the inmate from making multiple calls checking their balance. There is no need.

Other posts by this author

|

2023 may 31

|

2023 mar 20

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

More... |

Replies