Transcription

Case 1:09-cv-02379-CLS-HGD Document 60-13 Filed 04/04/11 Page 5 of 6

FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER

Southern District of Texas

Lyric Office Centre

440 Louisiana Street, Suite 1350

Houston, Texas 77002-1669

FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER:

MARJORIE A. MEYERS

First Assistant:

H. MICHAEL SOKOLOW

Telephone:

713.718.4600

Fax:

713.718.4610

September 27, 2010

Mr. Michael Schultz

Asst. United States Attorney

919 Milam St., Suite 1500

Houston, TX 77002

RE: Jeremy Pinson, Reg. No. 16267-064

Dear Mr. Schultz:

Again, I write to you on behalf of Jeremy Pinson. You will recall that you advised the Bureau of Prisons that Mr. Pinson was to be kept separate from certain inmates and prison gangs. He is currently housed at the Federal Correctional Institution in Taladega, Alabama. Unfortunately, he continues to be subjected to attacks by gang members.

In light of the continued attacks, Mr. Pinson requests that he be placed in the Witness Protection Program. Further, in addition to the previously identified gangs, he must be kept separate from the California Mexican Mafia and the Aryan Brotherhood. Also, he is no longer a member of the Sureno gang and should not be so classified.

This matter is of some urgency. Please send a letter to the appropriate designation unit in Grand Prairie, Texas, as well as to Warden John Rathman, 565 E. Renfroe Road, Talladega, Alabama, 35160.

Thank you for your assistance in this regard.

Very truly yours,

Marjorie A. Meyers

Federal Public Defender

Southern District of Texas

cc: Mr. Ed Gallagher, SAUSA

***

(12/9/2009)

From: [redacted]

To: [redacted]

Date: 12/9/2008 2:22 PM

Subject: This morning's conversation

Mike,

I have reviewed the materials I received from the OIG's Dallas Field Office regarding the interview of former Victorville FCC Inmate Jeremy Pinson, Reg. No. 16267-064. As I discussed with you this morning, the OIG's Los Angeles Field Office (LAFO) already had an open investigation on one of the FCC staff members referred to in the Dallas interview. The information provided to the OIG by Pinson in the Dallas interview corroborated some of the information the LAFO received from an independent source in the original LAFO investigation, so I decided to merge the new information into the open case. In other words, 2 independent sources provided similar information regarding illegal activities being perpetrated by FCC staff. Based on that information, it appears there may be some validity to the information Pinson provided the OIG, including his concern for his safety and well-being. Regarding the list of 25 names (staff and inmates) we also spoke about this morning, I can confirm that they are all referred to in the report I received from the Dallas Field Office. I apologize for not including more names in this message, but it is an open criminal case and I do need to maintain the integrity of the investigation. Thanks and please let me know if you need anything further.

[redacted]

Special Agent

U.S. Department of Justice-OIG

Los Angeles Field Office

FOI Exempt

***

FD-302 (Rev. 10-6-95)

FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION

Date of transcription: 11/01/2011

JEREMY VAUGHN PINSON, date of birth February 6, [redacted], inmate registration number 16267-064, inmate housed at the United States Penitentiary - Administrative Maximum Security (ADX), 5880 Highway 67 South, Florence, Colorado, telephone number (719) 784-9464, was interviewed. PINSON was advised of the identities of his interviewers and thereafter furnished the following information:

PINSON is serving a federal sentence for threatening the President of the United States, threatening a jury member, threatening a secret service agent, and threatening a federal judge. PINSON is a member of a Sureno gang known as Florencia 13, subset Florencia Termites. PINSON is currently assigned to the ADX for attempting to murder a MS-13 gang member who cooperated with the FBI and attempting to stab a Federal Bureau of Prison (BOP) correctional officer. The attempted murder occurred at the Special Management Unit (SMU) located at the federal correctional facility in Talladega, Alabama. Since being transferred to the [redacted] has been green lit (1 - Green lit refers to a gang authorizing and ordering other gang members to attempt murder someone) by the Mexican Mafia (2 - Sureno gangs remain loyal to the Mexican Mafia as the governing body over all Sureno gangs. The number 13 refers to the letter M (13th letter of the alphabet), for Mexican Mafia) for being labeled as a cooperator with the FBI.

Prior to his current charges, PINSON transported large amounts of cash from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma to Los Angeles, California for Florencia 13. In November, 2003 PINSON transported his last shipment to Los Angeles. The shipment was approximately $2,000,000.00 in cash and Florencia 13 transported this amount 6 times a year. The money was combined with a shipment of illegal weapons that were used to purchase Heroin, Methamphetamine, and Marijuana from the Sinaloa Cartel. The drugs were transported from a large residence located at [redacted]. Once picked up in Nayarit the drugs were stored in tires that were loaded on a semi-trailer and transported to San Diego, California or Nueva Laredo, Texas by [redacted]. The drugs transported to San Diego, California were later shipped to the Huntington Park area of Los Angeles for further distribution. One of the distribution locations was to the South Side Locos (3 - The Southside Locos are a Sureno gang subset) in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The location where the drugs are delivered is [redacted].

On August 3, 2010 BOBBY COWLEY was murdered while incarcerated at the SMU in Talladega, Alabama. [redacted] of the Aryan Brotherhood (4 - The Aryan Brotherhood or AB is a white supremacist gang. In recent years the AB has aligned with the Mexican Mafia) stabbed COWLEY to death. COWLEY was green lit by [redacted] of the Aryan Brotherhood and [redacted] of the Mexican Mafia. [redacted] held the shank (5 - A shank is a homemade knife created and used by inmates) for [redacted] prior to the stabbing and produced it for him at the time of the stabbing. The green light was communicated to [redacted] via a cellular telephone that was smuggled into the prison facility by a BOP correctional officer named First Name Unknown (FNU) [redacted]. FNU [redacted] received $500.00 from an inmate named [redacted] for smuggling the telephone in to the inmates. A man using the moniker [redacted] telephoned from [redacted] to [redacted] to notify him of the green light on COWLEY.

In January, 2005 ERIC HENDERSON was murdered in the Huntington Park area of Los Angeles, California. HENDERSON was shot by [redacted] because he was a black man in an area that was green lit by the Mexican Mafia. [redacted] of the Mexican Mafia authorized the green light on all black gang members in that area of Los Angeles. The area where HENDERSON was murdered is a Sureno neighborhood. [redacted] was later indicted on unrelated charges and was since incarcerated. It is unknown if the homicide was ever solved. PINSON discovered this information while incarcerated at the Lawton Correctional Facility in Lawton, Oklahoma. A man using the Moniker [redacted] called PINSON on a smuggled cellular telephone that PINSON had purchased from a female staff member at the private state correctional facility for $300.00 to notify him of the homicide.

PINSON produced the following telephone numbers that he retained from the time period when he was delivering money from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma to Los Angeles, California:

[numbers all redacted]

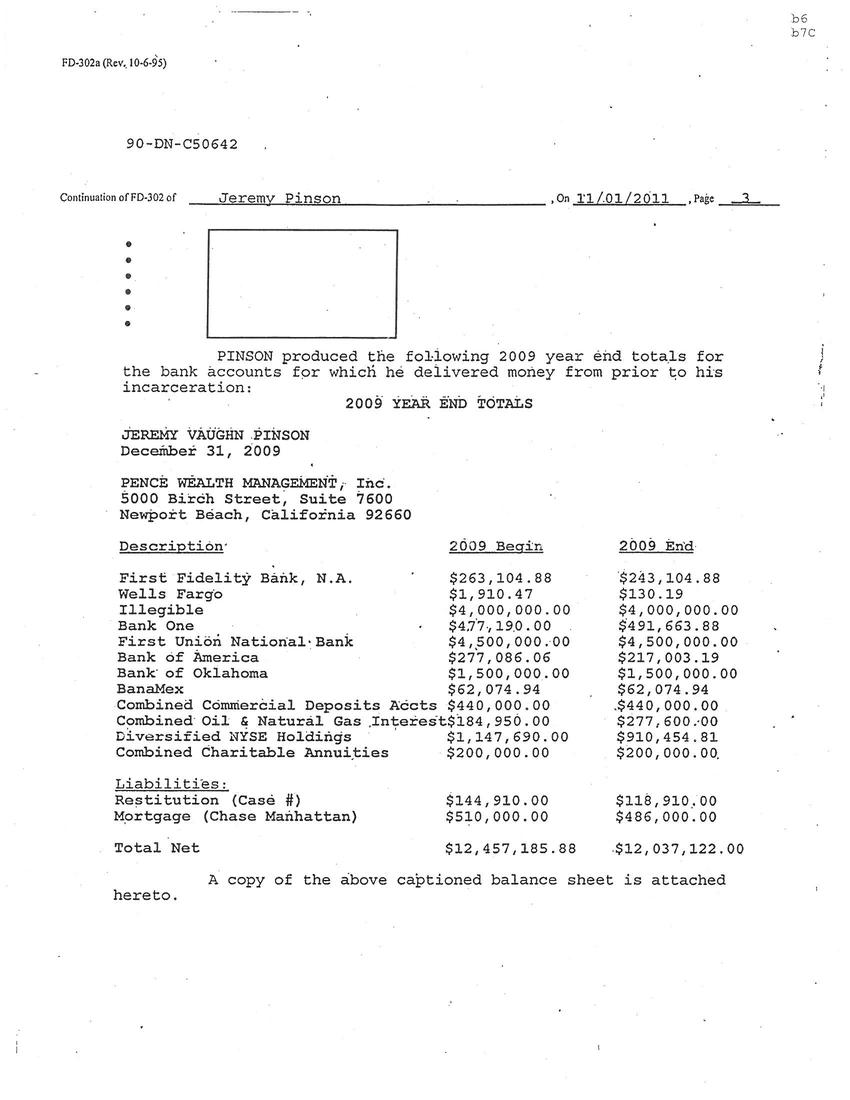

PINSON produced the following 2009 year end totals for the bank accounts for which he delivered money from prior to his incarceration:

2009 YEAR END TOTALS

JEREMY VAUGHN PINSON

December 31, 2009

PENCE WEALTH MANAGEMENT, INC.

5000 Birch Street, Suite 7600

Newport Beach, California 92660

Description - 2009 Begin - 2009 End

First Fidelity Bank, N.A. - $263,104.88 - $243,104.88

Wells Fargo - $1,910.47 - $130.19

Illegible - $4,000,000.00 - $4,000,000.00

Bank One - $477,190.00 - $491,663.88

First Union National Bank - $4,500,000.00 - $4,500,000.00

Bank of America $277,086.06 - $217,003.19

Bank of Oklahoma - $1,500,000.00 - $1,500,000.00

BanaMex - $62,074.94 - $62,074.94

Combined Commercial Deposits Accts - $440,000.00 - $440,000.00

Combined Oil & Natural Gas Interests - $184,950.00 - $277,600.00

Diversified NYSE Holdings - $1,147,690.00 - $910,454.81

Combined Charitable Annuities - $200,000.00 - $200,000.00

Liabilities:

Restitution (Case #) - $144,910.00 - $118,910.00

Mortgage (Chase Manhattan) - $510,000.00 - $486,000.00

Total Net - $12,457,185.88 - $12,037,122.00

A copy of the above captioned balance sheet is attached hereto.

***

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

HOUSTON DIVISION

JEREMY V. PINSON,

Movant/Defendant,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Respondent/Plaintiff.

CRIMINAL NO. H-08-283

CIVIL NO. H-10-4380

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER

Federal inmate Jeremy Pinson has moved under 28 U.S.C. 2255 to vacate his conviction and sentence. Pinson pleaded guilty and entered into a plea and cooperation agreement. The agreements Pinson signed and swore to in open court, under oath, included a waiver of his rights to appeal and to file collateral challenges when the judgment became final. No direct appeal was filed. In his 2255 motion and amended motion, Pinson asserts that the government violated the plea agreement by failing to: request that the Bureau of Prisons place him in the WITSEC Program, file a motion at sentencing recommending that the Bureau of Prisons grant a downward management adjustment, and file a motion for downward departure based on substantial assistance. He also asserts that his trial counsel failed to file a direct appeal. Although Pinson filed his 2255 motion pro se, after this court set an evidentiary hearing, counsel was appointed to represent him.

Based on the motions and responses, the parties' submissions, the record, the evidence at the hearing, the arguments of counsel, and the applicable law, this court finds that Pinson's allegations are without basis and that his claims do not allow for the relief he seeks. The 2255 motion is denied, and the civil action is dismissed, with prejudice. Final judgment is entered by separate order.

The reasons are set out below.

I. Background

Pinson has a lengthy history in the state courts and prison system, the federal courts, and the federal Bureau of Prisons. He has had a number of violent encounters in the prison systems and has been in a number of facilities.

The events leading up to this 2255 motion began with his May 2008 indictment in his division for mailing threatening communications, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 876. (Docket Entry No. 1). On November 5, 2008, Pinson pleaded guilty to the indictment and entered into a written plea agreement, which included waivers of his direct appeal and collateral challenge rights. (Docket Entry No. 38).

A. The Rearraignment Hearing and Plea Agreement

As stated in the written plea agreement that Pinson signed, and in exchange for Pinson's guilty plea, financial disclosures, and appellate waivers, the government agreed not to oppose a sentence at the low end of the guideline sentencing range, credit for acceptance of responsibility should Pinson accept responsibility for his crime, and an additional sentencing level reduction if Pinson's final guideline level was 16 or above. The government also agreed to recommend to the court that Pinson be placed in the U.S. Prison Coleman #2 facility in Coleman, Florida. The government agreed that Pinson's criminal history category was VI, making his guideline level 10, following a two-level reduction for acceptance of responsibility. Lastly, the government agreed to recommend that the BOP grant Pinson a downward management adjustment. The court granted an oral motion to waive a PSR for this sentencing, because a PSR had been prepared relatively recently for Pinson's prior federal sentencing. (Docket Entry No. 36).

This court held a thorough Rule 11 hearing on the guilty plea. (Docket Entry No. 81). In response to questions about whether he had been treated for any mental illness or was taking any medications, Pinson reported that he had been treated for depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and borderline personality disorder, and was seeing a psychologist weekly for counseling. (Id., at 4-5). Pinson advised that he was taking a sedative for sleeping, but no other psychotropic medication. (Id., at 5-6). Pinson advised that the medications he took did not interfere with his ability to understand the charges or the proceedings. (Id., at 4-7). Both Pinson's lawyer and the Assistant United States Attorney stated their belief, based on their own personal observations of Pinson, that he was fully competent to plead guilty. Based on its own observations of Pinson, his obvious understanding of all the court's questions, and his clear and logical responses, as well as all the information from prior hearings at which Pinson had appeared, this court found that he was fully competent to enter a knowing, voluntary, and informed plea, and that he had done so. The following exchange occurred at the Rule 11 hearing:

THE COURT: Okay. Have you had enough time to talk with your lawyer?

THE DEFENDANT: I have, Your Honor.

THE COURT: We took some considerable steps to make sure that you had an improved ability to contact your lawyer and communicate with him. With those steps have you had sufficient ability to communicate with your lawyer to prepare for this hearing?

THE DEFENDANT: I have, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Are you satisfied with the advice and the help that your lawyer has given you?

THE DEFENDANT: Absolutely, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Good. Do you want to ask him any more questions, consult with him further in any way, or get any more advice from him before we go on?

THE DEFENDANT: No, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Okay. All right. Mr. Ely, have you had enough time to investigate this case?

THE DEFENDANT: Yes, Your Honor, I have.

THE COURT: The problems that brought us to some prior hearings about your ability to communicate with your client, were those resolved sufficiently to allow you enough access to, both, be prepared and to prepare your client.

MR. ELY: Yes, Your Honor. The move back to the Federal Detention Center has greatly facilitated my ability to work with Mr. Pinson. The Federal Detention Center personnel have been making the phone available occasionally and we've had a number of lengthy face-to-face meetings recently, as well as several telephone conversations. So we have been able to consult and deal with various decisions that my client has to make. He had, in the past, requested to proceed pro se before the Court and withdrawn those requests. That was more in the nature of the problem he was having with conferences with counsel. But I will say for the record that our ability to communicate and my ability to counsel with him has resulted in a, you know, a healthy attorney-client relationship, and there are no problems. And that given the history of pretrial motions of this case, that should not be a concern to the Court because Mr. Pinson has been able to assist me in every respect. And he and I have had sufficient opportunity to prepare for this hearing.

THE COURT: Are you satisfied that Mr. Pinson fully understands the charges he faces and the punishment he faces?

MR. ELY: Yes, Your Honor, I am.

THE COURT: Has he been able to cooperate with you fully?

MR. ELY: Yes, he has.

THE COURT: You've had a lot of opportunity to observe Mr. Pinson, to talk with him, at length. Do you have any doubts as to his competence?

MR. ELY: No, Your Honor. I've had a lot of opportunity. Mr. Pinson, I know he indicated he only had a sixth grade education. He is very high functioning intellectually in terms of his ability to deal with me and to cooperate in his own defense. He has a number of medical problems. Those problems have not to date, particularly in the recent past, caused any difficulties in us being able to discuss what his situation is and make - for him to make informed decisions. So I'm satisfied that he understands, both, the charges, the maximum punishment, and has been extremely helpful in working with this case out with me.

THE COURT: All right. The Court has also had an usually extensive opportunity to see Mr. Pinson, talk with him. And based on those opportunities, as well as this hearing, statements of counsel and the record, the Court finds that Mr. Pinson is indeed competent to enter a knowing and voluntary and informed plea.

(Id., at 7-9)

The court specifically, and in detail, admonished Pinson about the significance of the appellate and collateral challenge rights he was waiving in the plea agreement, and Pinson confirmed that he understood. (Id., at 15-20). Pinson acknowledged that he had discussed the plea agreement with defense counsel, Federal Public Defender Richard Ely, and had no further questions for him. After this court provided additional explanations of the waivers in the plea agreement, Pinson stated that he fully understood the rights he was waiving, including the right to bring this action, and was knowingly waiving these rights. (Id.).

The court also specifically told Pinson that the government was under no obligation to seek a downward departure for substantial assistance under U.S.S.G. 5K1.1 and had made no guarantees or promises about any such motion or departure. Pinson stated that he understood. (Id., at 20). The court told Pinson that the government had agreed to recommend that he be designated to the Coleman, Florida facility and placed in downward management, but also told Pinson that those recommendations were not binding on the BOP and that he could not file an appeal or collateral challenge if they were not acted on. The following colloquy occurred:

THE COURT: The government has said that, in the event you cooperate and provide information, substantial assistance, it will consider whether it should file a motion asking the Court for a lower sentence based on that. Do you understand that?

THE DEFENDANT: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: What you need to understand is that the government reserves to itself the right to decide whether whatever cooperation or assistance you provide is enough to justify a motion for a lower sentence. If for whatever reason the government decides it's not, there's nothing you or I can do about that. Do you understand?

THE DEFENDANT: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Do you understand there is no guarantee or promise made by the government or anyone else, that if you provide assistance or cooperate, that's going to result in a lower sentence?

THE DEFENDANT: I understand, Your Honor.

THE COURT: The government has agreed that it would recommend that you be placed in a particular facility in Florida. Again, that is - two points: Number one, I don't have to follow that recommendation on the part of the government; and, two, no recommendation that the government or I make is binding on the Bureau of Prisons. So even if we make that recommendation, it might not happen. Do you understand that?

THE DEFENDANT: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: And that would not give you an opportunity to withdraw your plea, file an appeal or file a later challenge. Do you understand that?

THE DEFENDANT: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Okay. Similarly, the government has agreed to recommend that the Court recommend that the BOP, Bureau of Prisons, grant you a downward management adjustment. Same point: I don't have to make that recommendation, and the Bureau of Prisons doesn't have to accept that. Do you understand?

THE DEFENDANT: Yes, Your Honor.

(Id., at 19-20). This Court found Pinson's guilty plea and waivers voluntary, informed, and knowing and accepted his guilty plea to the indictment. (Id., at 27).

At sentencing, the court heard extensive allocution from Pinson. The court also engaged in lengthy conversation with the attorney about whether Pinson's sentence should be concurrent or consecutive to the undischarged prior federal sentence, and how to reflect the terms of the plea and cooperation agreements. The government and the court both recommended that the BOP place Pinson at the Coleman, Florida facility he requested. The government also recommended that the BOP give Pinson a downward management adjustment. The court heard from BOP representatives who were present about some of the considerations and constraints involved in Pinson's designation to a particular facility, given the security problems presented by an extensive history of both cooperation and aggression, as well as his need for mental health services. The court imposed the following sentence:

THE COURT: I do agree that the appropriate sentence is at the low end of the guidelines, which is 24 months. That is consistent with the plea agreement, that leaves the objectives under 3553A, as well as the factors under the guidelines. With respect to how much of that should be consecutive and how much of that should be concurrent, it's not a huge separation between what the government has recommended and what Mr. Ely has recommended. And I believe the appropriate solution is somewhere in between both their positions. It is therefore this court's judgment that of the 24 [month] sentence, 12 months of that be concurrent, including the six months you've already served, and that 12 months be consecutive. And that is to the undischarged term you are presently serving as a result of your convictions in the Western District of Oklahoma case.

****

With respect to the recommendations, I certainly agree that it is appropriate to recommend that you be designated to the Coleman Number 2 facility in Coleman, Florida. That appears to meet the, at least right now, meet the requirements for separation that are obviously important. I also recommend to the Bureau of Prisons that they consider you for designation to an appropriate facility with mental health services... [T]he combination of Mr. Pinson's mental and physical needs and the drugs required to deal with both of those sets of conditions, merit a full-blown diagnostic and treatment regimen by appropriate professionals. And I don't believe that those are routinely available at the level that seem to be appropriate here throughout the prison system. So I strongly recommend that Mr. Pinson be considered for designation for at least a detailed evaluation at one of the facilities that has that kind of expertise available.

****

THE COURT: I'm most troubled by the request for a recommendation for a downward management adjustment for administrative purposes.

MR. ELY: That's basically a security level decrease, Your Honor.

THE COURT: That is something that I am concerned about because that really does intrude the Judge more deeply into the Bureau of Prisons' expertise... I do... recommend strongly that the Bureau of Prisons consider all available mechanisms for meeting the following plea criteria: One, Mr. Pinson's safety; two, given the length of his prison sentence, avoiding extended indefinite periods of single cell or other forms of administrative segregation; and, three, access to medical care. And that should include but not be limited to the state placement program. It may include downward management adjustments, but certainly reliance on indefinite administrative segregation to keep Mr. Pinson safe seems to me to be unacceptable. At least highly undesirable.

THE COURT: So I'm going to make my recommendation a little bit different from the way you asked for it, not limit it to or specifically target it to a downward management adjustment, but rather ensuring placement in a facility that will both permit security and something other than indefinite segregation.

(Docket Entry No. 82, at 40-45).

On December 8, 2008, the court sentenced Pinson to 24 months imprisonment, 12 months of which were to run concurrently with Pinson's undischarged federal sentence from his Oklahoma convictions. (Docket Entry Nos. 46, 50). The court admonished Pinson that if he believed any appellate rights survived his waiver, he had to file his notice of intent to appeal within the appropriate time after the judgment was entered. Pinson stated that he understood and, with counsel present, stated that he did not intend to appeal:

THE COURT: I don't believe that under the plea agreement there are any grounds for appeal that survive the plea agreement.

MR. ELY: No, Your Honor.

THE COURT: If you believe otherwise, Mr. Pinson, you may file a notice of intent to appeal within 10 days from the date the judgment is entered. If you fail to do it within that time limit, you may waive any remaining right that is present. I also instruct you that if you do file an appeal and want a lawyer to be appointed, you may ask the Court to appoint one for you if you cannot afford one. Do you understand those rights?

THE DEFENDANT: I do, Your Honor. I don't intend to appeal.

(Docket Entry No. 82, at 49)

The judgment was entered on December 15, 2008. (Docket Entry No. 50). Pinson did not appeal his conviction or sentence. His conviction became final on December 29, 2008, 14 days later.

B. The 2255 Motions

On November 4, 2010, Pinson filed his initial motion under 28 U.S.C. 2255 to vacate, set aside, or correct his sentence. (Docket Entry No. 52). On May 6, 2011, Pinson filed an amended 2255 motion. (Docket Entry No. 68). In the amended motion, Pinson expanded on his previously raised complaint that the government violated the plea and cooperation agreement by adding background allegations that the government encouraged Pinson to lie during an FBI debriefing. Pinson alleged that his refusal to lie led the government to retaliate by declining to sponsor Pinson for the WITSEC Program or to move for a 5K1.1 motion reducing his sentence, and to government agents seizing Pinson's property during his stays at different prison facilities within the BOP.

In his original motion, Pinson claimed that his trial counsel had failed to perfect his direct appeal. Pinson alleged that after his lawyer, Ely, had left the Federal Public Defender office and ceased representing him, the Federal Public Defender for the Southern District of Texas, Marjorie Meyers, led him to believe a direct appeal had been filed by her office on his behalf.

In his amended motion, Pinson also added a new ineffective assistance claim, asserting that Ely was deficient before the rearraignment in failing to obtain a competency examination to determine if Pinson was competent to stand trial or to plead guilty and whether he could have qualified for an insanity defense to the crime he pleaded guilty to. Pinson also added the new allegation that his guilty plea was involuntary because he had been kept in relative isolation, deprived of sleep, harassed, and exposed to oleoresin capsicum, fear, and duress.

The government responded to the motions and moved to dismiss or, in the alternative, for summary judgment. (Docket Entry No. 88). The government urged that: Pinson's motions were untimely and equitable tolling did not apply; Pinson had voluntarily, effectively, and validly waived his right to appeal or to file a collateral challenge; and Pinson had received effective assistance of counsel, and that his substantive claims were without merit.

C. The Evidentiary Hearing

Because the affidavits filed by Pinson and by his trial counsel, Richard Ely, conflicted as to whether Pinson had instructed Ely to file a direct appeal, this court held an evidentiary hearing on the issue of whether Pinson had given such instruction. Pinson testified at the hearing that although he knew he had waived his appellate rights in his plea agreement, approximately seven to ten days after he pleaded guilty, he changed his mind. He testified that his decision to seek relief was based on the government's failure to "debrief" further, which, in his mind, would prevent the government from assessing whether he should receive a motion from downward departure based on substantial assistance. Because Pinson's legal papers had been seized when he was in Oklahoma at a transitional facility, due to a fire in the cell set by his cellmate, he did not have Ely's contact information and did not communicate with him until the end of 2008 or early 2009, when Ely called him to see if he had received the Judgment and Statement of Reasons. In that telephone call, according to Pinson, he told Ely that he was concerned that the government was not living up to its end of the cooperation agreement because it was not seeking additional debriefing. Pinson testified that he asked Ely to do what was appropriate to have the government finish the debriefing so he could be evaluated for a substantial assistance motion. Pinson also mentioned that he had some concerns for his safety in the facility where he was housed. Pinson agreed that he did not explicitly ask Ely to file an appeal. Pinson asserts he asked Ely to take appropriate steps to require the government to comply with the plea agreement. (Docket Entry No. 107, at 17, 21).

Pinson was transferred to the Coleman facility in Florida from the transit facility in Oklahoma in early 2009. In June 2009, Pinson again had his papers and other belongings seized, this time because he had a fight with another inmate. In August 2009, Pinson was transferred to a special management unit of the BOP in Alabama. Some of the legal papers that had been removed from him were not returned. Pinson asserts that he wrote Ely letters in which he used the word "appeal". Those letters are not part of the record, despite ample opportunity provided by this court for Pinson to obtain them.

In early 2010, according to Pinson, because Ely had left the FPD and taken a new position in Washington, D.C., he talked to Marjorie Meyers, the Federal Public Defender in Houston. She told him that if he wanted to debrief with the government, he should send the government a letter offering to do so.

Pinson testified that in November 2010, he called the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals to check on the status of his appeal, which he had assumed was in the briefing stages. He learned that no appeal was pending. He filed his motion under 2255, which he had been working on since early that year, in November 2010.

Ely testified at the hearing as well. He stated that before Pinson pleaded guilty, they talked extensively about the waiver provisions in the plea agreement and that Pinson understood them. Ely testified that he told Pinson that, given the government's agreements, Pinson had received the benefit of the plea bargain. Ely testified that Pinson did not ever instruct him to appeal. Instead, in their conversations, they discussed Pinson's concerns for his safety from other inmates, his problems at each of the facilities he was designated to, and matters unrelated to the case.

FPD Meyers also testified about her conversations with Pinson after Ely had left the Public Defender office. She testified that Pinson's primary concern was that he be housed apart from people he had provided information to the government about in the past. She did not recall any concern on Pinson's part that he had not been allowed to finish debriefing. In March 2011, Pinson wrote a letter to another lawyer at the Public Defender's office, stating that he had two concerns about the government's failure to live up to the plea agreement. One was that he had not been placed in the witness security program by the BOP. The second was that he had not been contacted by the government about debriefing. The record shows that there was contact by an AUSA in Alabama to obtain some information from Pinson, but the results of that are not clear from the record.

Each of Pinson's allegations - that Ely and the Federal Public Defender provided ineffective assistance both pretrial and in failing to file a direct appeal; that his guilty plea was involuntary because of government-sponsored isolation, sleep deprivation, harassment, oleoresin-capsicum exposure, and fear and duress; that the government violated the plea and cooperation agreement by failing to follow through on promises to sponsor Pinson for the WITSEC program and to file a 5K1.1 motion; and that the government directed BOP agents to seize Pinson's property in retaliation for his refusal to lie during an FBI debriefing - is analyzed below, based on the record and the applicable law.

II. The Legal Standards

A 2255 motion "provides the primary means of collaterally attacking a federal conviction and sentence." Jeffers v. Chandler, 234 F.3d 277, 279 (5th Cir. 2000) (citation omitted). Relief under a 2255 motion "is warranted for errors that occurred at trial or sentencing." Id. A 2255 motion requires an evidentiary hearing unless the motion, the files, and the record conclusively show the prisoner is entitled to no relief. United States v. Bartholomew, 974 F.2d 39, 41 (5th Cir. 1992). A "collateral challenge may not do service for an appeal." United States v. Shaid, 937 F.2d 228, 231 (5th Cir. 1991) (en banc)), cert. denied, 502 U.S. 1076 (1992) (quoting United States v. Frady, 456 U.S. 152, 165 (1982)). A movant is barred from raising claims for the first time on collateral review unless he demonstrates cause for failing to raise the issue on direct appeal and actual prejudice resulting from the error. Id. at 232 (citations omitted). If the error is not of constitutional or jurisdictional magnitude, the defendant must show that "the error could not have been raised on direct appeal, and if condoned, would result in a complete miscarriage of justice." Id. at 232 n.7, quoted in United States v. Pierce, 959 F.2d 1297, 1301 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 1007 (1992). In Bousley v. United States, 523 U.S. 614 (1998), the Supreme Court held that a petitioner can successfully petition for 2255 relief after a guilty plea only if: (1) the plea was not entered voluntarily or intelligently, or (2) the petitioner establishes that he is actually innocent of the underlying crime. See id. at 621-24.

The threshold issue, whether this motion is time-barred, is addressed first.

III. Timeliness

Under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 ("AEDPA"), Pub. L. No. 104-132, 110 Stat. 1214 (1996), all petitions or motions for collateral relief under 28 U.S.C. 2255 filed after April 24, 1996 are subject to a one-year limitations period found in 28 U.S.C. 2244(d). The limitations period expired on December 29, 2009, one year from the date on which the judgment of conviction became final. 28 U.S.C. 2255(f)(1). Pinson filed his initial motion on November 24, 2010. He alleged that the time-bar is subject to equitable tolling. In support, Pinson attached a memorandum dated June 28, 2010, by a counselor at the prison, explaining that Pinson was unable to access his "legal property" due to its seizure by the BOP SIS Office at the FBI's request. (Docket Entry No. 68, Ex. 10).

On May 6, 2011, Pinson filed an amended 2255 motion. The amended motion, in part, expanded the factual basis for the grounds asserted in the initial motion - that Pinson's trial counsel failed to file a direct appeal and that the government had breached the plea agreement. The date of these claims relate back to November 2010. See Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 15(c). But the amended motion also asserts new ineffective assistance claims based on Ely's failure to obtain a competency examination and new claims that Pinson's guilty plea was involuntarily obtained through prosecutorial misconduct. These claims assert "a new ground for relief supported by facts that differ in both time and type from those the original pleading set forth", and do not relate back to the November 2010 filing. United States v. Gonzalez, 592 F.3d 675, 680 (5th Cir. 2009) (quoting Mayle v. Felix, 545 U.S. 644, 650 (2005)).

Both the November 2010 and the May 2011 motions are time-barred unless equitable tolling applies. Equitable tolling is permitted only "in rare and exceptional circumstances." Davis v. Johnson, 158 F.3d 806, 811 (5th cir. 1998), cert. denied, 121 S. Ct. 622 (2000); see also Fisher v. Johnson, 174 F.3d 710, 713 (5th Cir. 1999). Courts must "examine each case on its facts to determine whether it presents sufficiently "rare and exceptional circumstances" to justify equitable tolling." Id. (quoting Davis, 158 F.3d at 811). Pinson must show "(1) that he has been pursuing his rights diligently, and (2) that some extraordinary circumstance stool in his way" of timely filing his 2255 motion. See Lawrence v. Florida, 549 U.S. 327, 336 (2007).

Pinson argues that the BOP's seizure of his possessions, including his legal papers, once in January 2009 and twice in June 2009, excuses his failure to file his 2255 motion until November 2010. In late 2008 or early 2009, Pinson testified that he talked to Ely and told him that he wanted to take steps to have the government finish its part of the plea and cooperation agreements by having him debrief. Although he testified that he assumed briefs were being prepared, Pinson knew that he was not receiving any documents or other information that an appeal would generate, from Ely or anyone else at the Federal Public Defender's Office. Pinson knew that Ely had taken a different job and that no other attorney had contacted him. Pinson knew that the government had not sought additional debriefing opportunities with him and had not filed a 5K1.1 motion. Despite the continuation of what Pinson alleged were breaches of the government's obligations under the plea agreement, his testimony that he had asked Ely to pursue ways to enforce these obligations, the absence of any activity relating to an appeal or other enforcement efforts, and his awareness that Ely was no longer assigned to his case, Pinson did not attempt to contact the Federal Public Defender's Office or the Fifth Circuit until late 2009. (Docket Entry No. 107, at 33). Pinson learned in early 2010 from the Fifth Circuit that no appeal had been filed. (Id., at 34). He spoke with Marjorie Meyers, the Federal Public Defender, three times in early 2010, learning the same information. (Id., at 35-36). Pinson did not write to the Federal Public Defender until May 2011. (Id., at 72-73). This does not amount to due diligence on Pinson's part. See Fisher v. Johnson, 174 F.3d 710, 715 (5th Cir. 1999) (holding that a habeas petitioner was not entitled to equitable tolling when, for a brief period of time, he lacked access to legal materials, was medicated, was separated from his glasses, and suffering from a post-traumatic stress syndrome attack because he did not diligently pursue his rights during the rest of the limitations period).

The record also fails to support Pinson's argument that he was hindered in filing his 2255 motion because of the property seizures. After the January 2009 seizure of his legal papers, he filed suit against the Bureau of Prisons and sought a protective order and a preliminary injunction, and contacted a Federal Public Defender in Florida. (Docket Entry No. 107, at 28). He was clearly able to exercise his right of access to the courts.

After the January 2009 seizure, Pinson received copies of his case file from the Federal Public Defender's Office in Houston. He had those papers until June 1, 2009, when a second seizure took place. These seizures occurred at the Coleman USP in Florida; Pinson asserts that those materials were never returned. A third seizure took place on June 25, 2009, as a result of what Pinson described as an "altercation" with his cellmate and another inmate. (Id., at 40). A memo from a BOP official to Pinson's case manager states that the prison had taken Pinson's property but had returned it within two to three weeks, and had not sent any property or legal work to the FBI. The memo states that Pinson had pulled a homemade weapon, a shank, from an envelope marked "Legal" that did not have any legal documents belonging to Pinson in it. (Id., at 40-41; Docket Entry No. 88, Ex. 3). The record shows that, in February 2009, Pinson had received copies of his entire case file from the Houston FPD. He had those files in his cell until the June 1, 2009 property seizure. The record also shows that the late June 2009 seizure was short-lived.

Pinson's testimony that he did not have enough specific information to file a 2255 motion earlier than November 2010 is not supported by the record. As noted, he believed as early as December 15, 2008 that the government was not fulfilling its obligations under the plea and cooperation agreements. (Docket Entry No. 107, at 11). He knew that despite his conversation with Ely in approximately early 2009, he was not placed in the WITSEC program or given additional debriefing opportunities. He knew that he had not received any information or materials relating to an appeal. He knew in January 2010 that no appeal had been filed. (Id., at 34). Even without ready access to all his papers, he had enough information to file a 2255 motion well before December 29, 2009, when the one-year deadline expired. Pinson did not file his initial motion under 2255 until November 2010.

Pinson's status as a pro se litigant does not justify equitable tolling. United States v. Petty, 530 F.3d 361, 365-66 (5th Cir. 2008); Lookingbill v. Cockrell, 293 F.3d 256, 264 n. 14 (5th Cir. 2002). Further, lack of legal training, ignorance of the law, and unfamiliarity with the legal process are insufficient reasons to equitably toll the AEDPA statute of limitations, even for inmates with far less intelligence and experience with the legal system than Pinson. Felder v. Johnson, 204 F.3d 168, 171-72 (5th Cir. 2000).

Pinson also argues that the Federal Public Defender led him to believe that his direct appeal was progressing. In the evidentiary hearing, Pinson testified that he talked to the Fifth Circuit Clerk's Office in January 2010. After some telephone calls back and forth, he learned that in fact no appeal was on file. (Docket Entry No. 107, at 34). At that point, he took two steps. The first was to begin to prepare to file a 2255 motion. The second was to contact Marjorie Meyers at the Federal Public Defender's Office in Houston. Meyers could not have misled Pinson into believing that an appeal had been filed because at that point, Pinson knew that no appeal had been filed. And Pinson did not testify that Ely told him that an appeal had been filed. To the contrary, Pinson testified that he told Ely in late 2008 or early 2009 that he wanted Ely to do whatever was appropriate to get the government to place him in WITSEC and allow him to debrief further so his assistance could be evaluated for a possible motion under U.S.S.G. 5K1.1. Pinson knew that neither of those things had occurred. The record does not show rare or extraordinary circumstances that prevented Pinson from filing his 2255 motion within the statutory deadline. The record shows that Pinson was aware of the facts underlying his 2255 motion much earlier than November 2010 and that he did not pursue his claims with diligence.

Because Pinson cannot meet his burden of showing that equitable tolling applies to excuse his November 2010 filing, the May 2011 filing is clearly time-barred. Even if equitable tolling applied to permit the November 2010 filing, the claims for ineffective assistance before he pleaded guilty and for prosecutorial misconduct are barred because they do not relate back to the earlier date, and there is no basis in the record to extend equitable tolling to those newly added claims.

Although this court finds that limitations bars Pinson's 2255 motion and amended motion, the issues raised in those motions are addressed below.

IV. The Involuntary Guilty Plea Claim

Pinson claims that his guilty plea was a product of government-sponsored isolation, sleep deprivation, harassment, oleoresin capsicum exposure, fear, and duress, making the plea involuntary. The record fails to support his claims. Instead, the record affirmatively shows that Pinson voluntarily and knowingly entered his guilty plea. See Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238, 244 (1969) ("What is at stake for an accused facing death or imprisonment demands the utmost solicitude of which courts are capable in canvassing the matter with the accused to make sure he has a full understanding of what the plea connotes and of its consequence. When the judge discharges that function, he leaves a record adequate for any review that may be later sought and forestalls the spin-off of collateral proceedings that seek to probe murky memories.") At the Rule 11 hearing, this court specifically asked Pinson whether he was sick in any way that affected his ability to understand what was going on about him and to think clearly. The court also asked about Pinson's medications and his physical and mental condition. This court had ample opportunity to observe Pinson's alertness and his ability fully to comprehend the questions he was asked and to answer logically and appropriately. It had previous opportunities to observe Pinson as well, in earlier hearings; his appearance, demeanor, and condition at his Rule 11 hearing did not show any decline or deterioration.

"A guilty plea will be upheld on habeas review if entered into knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently." Montoya v. Johnson, 226 F.3d 399, 404 (5th Cir. 2000). The plea agreement fully advised Pinson of the elements of the offense and the punishment he faced, and this court admonished Pinson as to both in court. Pinson was advised of, and said, under oath and in open court, that he fully understood, the maximum possible penalty for his crime, including the potential fine and of supervised release. Pinson also stated, under oath and in open court, that he did not plead guilty because of any threats, coercion, or harm done to himself or others and that he did not plead guilty because of any promises other than those made in the plea agreement. He specifically stated that he was pleading guilty because he was guilty and for no other reason. (Docket Entry No. 81, at 22). His signed plea agreement and sworn testimony supports the finding that his plea was knowing, informed, and voluntary. A plea may be involuntary if there is such coercion or duress "that it creates improper pressure that would be likely to overbear the will of some innocent persons and cause them to plead guilty." United States v. Pollard, 959 F.2d 1011, 1021 (D.C. Cir. 1992), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 915 (1992) (citations omitted). "Only physical harm, threats of harassment, misrepresentation, or promises that are by their nature improper as having no proper relationship to the prosecutor's business (e.g., bribes) render a guilty plea legally involuntary." Id. The record here shows no such influence. Pinson's guilty plea was voluntarily made.

V. The Involuntary Waiver of Appellate and Collateral Challenge Rights Claim

A defendant may waive his right to appellate review and to postconviction relief under 2255 if the waiver was knowing and voluntary. United States v. White, 307 F.3d 336, 341 (5th Cir. 2002) (citing United States v. Wilkes, 20 F.3d 651, 653 (5th Cir. 1994)). For such a waiver to be knowing and voluntary, the defendant must know that he had a right to seek appellate and collateral review and that he was giving up that right. See United States v. Portillo, 18 F.3d 290, 292 (5th Cir. 1994) (discussing waiver of appellate rights). A claim of ineffective assistance of counsel may survive a waiver "when the claimed assistance directly affected the validity of that waiver or the plea itself." White, 307 F.3d at 343. As long as the plea and the waiver themselves were knowing and voluntary and the contested issue is the proper subject of a waiver, "the guilty plea sustains the conviction and sentence and the waiver can be enforced." Id. at 343-44.

"To determine whether an appeal of a sentence is barred by an appeal waiver provision in a plea agreement, [this court will]...conduct a two-step inquiry: (1) whether the waiver was knowing and voluntary and (2) whether the waiver applies to the circumstances at hand, based on the plain language of the agreement." United States v. Bond, 414 F.3d 542, 544 (5th Cir. 2005). In his plea agreement and in his Rule 11 hearing, Pinson knowingly and voluntarily waived his right to file a direct appeal or a 2255 motion. In the plea agreement, Pinson "waive[d] the right to contest his conviction or sentence by means of any postconviction proceeding..." (Docket Entry No. 38, at 3). When, as here, the defendant's plea agreement informs him of his right to appeal his sentence and states that, by entering the plea agreement, he forfeits that right, the waiver is enforceable if "the record of the Rule 11 hearing clearly indicates that a defendant has read and understands his plea agreement, and that he raised no question regarding a waiver-of-appeal provision..." Portillo, 18 F.3d at 292-93 (distinguishing United States v. Baty, 980 F.2d 977, 978-79 (5th Cir. 1992)); accord. Bond, 414 F.3d at 544 ("Because he indicated that he read and understood the agreement, which included explicit, unambiguous waivers of appeal, the [appellate] waiver was both knowing and voluntary.")

The rearraignment transcript in this case makes it abundantly clear that Pinson understood he was giving up his rights to appeal and to file a later collateral challenge. (Docket Entry No. 81, at 15-20). The following colloquy occurred:

THE COURT: You understand, Mr. Pinson, that, standing here today, you don't know what sentence you're going to get. All you know for sure is that it can't be more than 10 years, and the fine can't go higher than a quarter million dollars?

THE DEFENDANT: I understand that, Your Honor.

THE COURT: If it turns out that the sentence you get is heavier than you expect, you can't withdraw your plea on that basis. Do you understand that?

THE DEFENDANT: I understand, Your Honor.

THE COURT: In fact, under this plea agreement, not only are you stuck with your plea, you can't file an appeal from the sentence or how it's determined, and you can't file any later collateral challenge to the conviction or sentence, with two exceptions. If the sentence is higher than the statute permits - which would mean I would have to sentence you to more than 10 years or fine you more than a quarter million dollars - then you can file an appeal or a later challenge. Or if I give you a sentence that's higher than the guidelines, the sentencing guidelines, and the government doesn't ask me to do that, then you can file an appeal. You still can't - or a later challenge. You still can't withdraw your plea. Do you understand that?

THE DEFENDANT: I do, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Bottom line is, that as long as I sentence you within the guidelines and the statute, you can't withdraw your plea, file an appeal or file a later challenge. Do you understand?

THE DEFENDANT: I understand, Your Honor.

(Docket Entry No. 81, at 15-16). Pinson again affirmed his understanding in the sentencing hearing, when he was told of the deadline for filing a notice of appeal but also reminded that it was unlikely any grounds for appeal survived his plea agreement. He stated that he understood and did not intend to appeal. (Docket Entry No. 82, at 49). The record affirmatively demonstrates that Pinson's appellate and collateral challenge waivers were knowing, informed, and voluntary.

VI. The Ineffective Assistance of Counsel Claims

Pinson attempts to overcome his waiver of his right to appeal and his earlier failure to raise the claims he now asserts by alleging ineffective assistance of counsel. The ineffective-assistance-of-counsel claims in this case do not provide a basis for relief.

The standard for judging the performance of counsel set out in Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984), requires the petitioner to prove (1) deficient performance and (2) resulting prejudice. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 697. Deficient performance is established by "show[ing] that counsel's representation fell below an objective standard of reasonableness." Id. at 688. To prove prejudice, "[t]he defendant must show that there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different." Id. at 694; see also United States v. Kimler, 167 F.3d 889, 893 (5th Cir. 1999) (applying Strickland). "A reasonable probability is a probability sufficient to undermine confidence in the outcome." Strickland, 466 U.S. at 694. On federal habeas review, scrutiny of counsel's performance "must be highly deferential", and the court will "indulge a strong presumption that strategic or tactical decisions made after an adequate investigation fall within the wide range of objectively reasonable professional assistance." Moore v. Johnson, 194 F.3d 586, 591 (5th Cir. 1999) (citing Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689). In assessing counsel's performance, a federal habeas court must make every effort to eliminate the distorting effects of hindsight, to reconstruct the circumstances of counsel's challenged conduct, and to evaluate the conduct from counsel's perspective at the time of trial. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689; Neal v. Puckett, 286 F.3d 230, 236-37 (5th Cir. 2002). "A court must indulge a 'strong presumption' that counsel's conduct falls within the wide range of reasonable professional assistance because it is all too easy to conclude that a particular act or omission of counsel was unreasonable in the harsh light of hindsight." Bell v. Cone, 535 U.S. 685, 701 (2002) (citing Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689). Federal habeas courts presume that trial strategy is objectively reasonable unless clearly proven otherwise. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689.

The second prong of the Strickland test looks to the prejudice caused by counsel's deficient performance. This requires "a reasonable probability that, absent the errors, the factfinder would have had a reasonable doubt respecting guilt." United States v. Mullins, 315 F.3d 449, 456 (5th Cir. 2002) (quoting Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687). "[T]he defendant must show that counsel's errors were prejudicial and deprived defendant of a 'fair trial, a trial whose result is reliable'." United States v. Baptiste, 2007 WL 925894, at *3 (E.D. La. Mar. 26, 2007) (quoting Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687). "This burden generally is met by showing that the outcome of the proceeding would have been different but for counsel's errors." Id. A defendant must satisfy both prongs of the Strickland test in order to be successful on an ineffective assistance claim. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 697. A court deciding an ineffective assistance of counsel claim is not required to address these prongs in any particular order. Id. If it is possible to dispose of an ineffective assistance of counsel claim without addressing both prongs, "that course should be followed." Id.

In Hill v. Lockhart, the United States Supreme Court held that the two-part Strickland standard was applicable to challenges to guilty pleas based on ineffective assistance of counsel. 474 U.S. 52, 58 (1985). With respect to the prejudice prong of Strickland, the defendant must show "that there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's errors, he would not have pleaded guilty and would have insisted on going to trial." United States v. Glinsey, 209 F.3d 386, 392 (5th Cir. 2000) (quoting Lockhart, 474 U.S. at 59).

A. The Pre-Plea Advice Claim

Pinson alleges that, although Ely was aware that he suffered from schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, epilepsy, and psychosis, and was under the influence of psychotropic medication, Ely failed properly to investigate his mental health status; obtain a competency examination to determine if Pinson was competent to stand trial or to plead guilty; and investigate whether Pinson qualified for the insanity defense for the crime of conviction. The record shows that although Ely or the AUSA could have moved for a hearing to determine Pinson's competency, there was "no reasonable cause to believe that the defendant may presently be suffering from a mental disease or defect rendering him mentally incompetent to the extent that he is unable to understand the nature or consequences of the proceedings against him or to assist properly in his defense." 18 U.S.C. 4241(a) (2008). The record shows that it was reasonable for Ely to believe that Pinson was competent to stand trial and to plead guilty, and that there was no need for further investigation. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 691; see also Wood v. Allen, - U.S. -, 130 S.Ct. 841, 850-51 (2010) (holding that a state court's factual finding that counsel made a strategic decision not to investigate further the defendant's mental illness was not unreasonable); Mickey v. Ayers, 606 F.3d 1223, 1237 (9th Cir. 2010) (holding that counsel's assistance was not ineffective when he made a reasonable strategic decision that justified not further investigating a mental health defense).

The record shows that Pinson had received several diagnoses of mental health and neurological disorders, for which he had long been receiving treatment. (Docket Entry No. 81, at 4-5). The record also shows, however, that defense counsel, the AUSA, and the court had opportunities to observe and talk with Pinson that were more extensive than is often true with defendants who plead guilty. Pinson had filed numerous motions, and the court had held several hearings in advance of the Rule 11 hearing. At the Rule 11 hearing, defense counsel described his extensive interactions with Pinson, particularly after the court arranged for Pinson to be moved to the Federal Detention Center, where he was very close to defense counsel's offices, to make communications easier. Counsel and the court had a good basis to judge Pinson's ability to enter a knowing, informed, and voluntary plea. Defense counsel, the AUSA, and the court all concluded that Pinson was fully competent. The record supports this conclusion.

At the rearraignment, Ely reported, in Pinson's presence, that after conferring extensively with Pinson, Ely found him to be competent. (Docket Entry No. 81, at 9). Ely specifically noted that despite little formal education, Pinson was "high functioning intellectually in terms of his ability to deal with [Ely] and to cooperate in his own defense." (Id.) Ely cited Pinson's "medical problems" and noted they did not interfere with Pinson's ability to discuss his many legal problems and "to make informed decisions". (Id., at 10). Ely concluded that Pinson "understands... the charges, the maximum punishment, and has been extremely helpful in working... this case out with me." (Id.) Indeed, the record shows that Pinson had worked with his counsel to vigorously pursue specific relief, including agreements from the government to make certain recommendations to the BOP.

The PSR from the Western District of Oklahoma, dated March 28, 2007 (19 months before the sentencing in this case) was reviewed by the court and the parties before sentencing. It showed Pinson's history of psychological disorders, and also indicated that he had a history of feigning symptoms to manipulate those around him. (PSR 71-94). A competency and insanity evaluation in 2006 concluded that Pinson was then competent to stand trial and not insane under federal standards. (PSR 89). There was no indication of any relevant change.

Pinson demonstrated his understanding of the law and his own legal situation in the pro se filings he had made before the rearraignment. He also demonstrated his competence in the way he conducted himself at the hearings in court. Although Pinson clearly suffered from mental health problems and illnesses, the record showed that he consistently understood what was going on around him, was able to cooperate with his counsel and to provide his lawyer with necessary information, and that he fully participated in the decisions impacting his defense. See Price v. Thurmer, 637 F.3d 831, 833-34 (7th Cir. 2011) ("The fact that a person suffers from a mental illness does not mean that he's incompetent to stand trial. He need only be able to follow the proceedings and provide the information that his lawyer needs in order to conduct an adequate defense, and to participate in certain critical decisions, such as whether to appeal." At sentencing, Pinson again demonstrated his full grasp of his legal situation. He gave a lengthy allocution that was logical and thoughtful. He explained that he had written the threatening letters that led to his conviction to change his prison setting and conditions to try to improve his safety. He explained his background and described his time in the state and federal criminal justice systems clearly. Nothing in Pinson's presentation to the court at the time of the guilty plea or the sentencing supports claims of incompetence or insanity or any need for further investigation.

The existing record reveals that counsel and the court were aware of Pinson's psychological conditions and history and determined that they neither provided a defense to the charges nor interfered with Pinson's ability to make a knowing, informed, and voluntary guilty plea. In light of counsel's reasonable perception that Pinson was competent, that Pinson did not exhibit any irrational behavior before the court, and the prior competency and psychological evaluations, it was reasonable for the court and for counsel not to require an additional competency evaluation. Defense counsel was also reasonable in not pursuing an insanity defense; to do so would have been futile. Pinson cannot show either deficient or prejudicial performance. He is not entitled to relief on these grounds.

B. The Failure to Perfect a Direct Appeal

Pinson claims that defense counsel was ineffective by failing to perfect a direct appeal. This court held an evidentiary hearing on Pinson's claim that he directed Ely to pursue a direct appeal, and was falsely led to believe that his appeal was being pursued. A lawyer who disregards specific instructions from the defendant to file a notice of appeal acts in a manner that is professionally unreasonable. Roe v. Flores-Ortega, 528 U.S. 470, 477 (2000) (citing Rodriquez v. United States, 395 U.S. 327 (1969)); see also Peguero v. United States, 526 U.S. 23, 28 (1999) ("[W]hen counsel fails to file a requested appeal, a defendant is entitled to [a new] appeal without showing that his appeal would likely have had merit.") A defendant who explicitly tells his attorney NOT to file an appeal plainly cannot later complain that, by following his instructions, his counsel performed deficiently. See Jones v. Barnes, 463 U.S. 745, 751 (1983) (holding that the defendant decides whether to take an appeal).

The evidentiary hearing record establishes that Pinson did not specifically instruct Ely to file an appeal and was not misled into believing that an appeal had been filed on his behalf. At the sentencing hearing held on December 8, 2008, Pinson stated that he did not intend to appeal. He testified at the evidentiary hearing that he changed his mind within seven to ten days. Pinson was, however, unable to talk to Ely until either the very end of 2008 or early 2009. When he did, he did not specifically tell Ely to appeal. Pinson's testimony about his phone call with Ely was as follows:

Q (by defense counsel). Now, you indicated that towards the end of your stay at Oklahoma City you had communication with Mr. Ely?

A. I did.

Q. When did that happen? Before the end of the year, right before the new year, if you recall?

A. I don't recall the exact date.

Q. How did that communication come about?

A. Mr. Ely contacted the Bureau of Prisons to set up a phone call, and he wanted to know if I had received a copy of my judgment and commitment order and the statement of reasons.

Q. Okay. How long - and did you speak with Mr. Ely?

A. I did.

Q. How long did this conversation last?

A. Probably 20 minutes.

Q. Okay. Did you ever broach the topic of an appeal with him?

A. I informed him of my concerns with the cooperation agreement, and I explained to him that I did not know specifically what the proper route for addressing the issue would be, whether that would be an appeal to the Fifth Circuit or whether it would be some type of motion to Judge Rosenthal. But I did indicate that I had a problem with what was being done, that I didn't feel the agreement had been fulfilled and I wanted to pursue some type of remedy.

Q. Did you - do you recall specifically asking Mr. Ely to file a notice of appeal at this point in your relationship with him?

A. I told him that whichever was the appropriate avenue for obtaining the relief I was requesting, that that was what I was asking him to do.

THE COURT: What relief were you requesting?

THE WITNESS: Well, the Government's agreement was that I was supposed to be debriefed.

THE COURT: So, you wanted to be debriefed?

THE WITNESS: And they would evaluate my -

THE COURT: Was that written down?

THE WITNESS: It was in my cooperation agreement.

THE COURT: Was that written down?

THE DEFENDANT: Yes, it was.

THE COURT: In the agreement?

THE WITNESS: It - it stated that I would cooperate with agents and that I would testify if necessary. I don't - I don't recall the specific language. I don't think it -

THE COURT: We can look at that. What relief were you seeking?

THE WITNESS: I was -

THE COURT: That you told Mr. Ely.

THE WITNESS: I was seeking for Mr. Ely to file some type of motion or appeal to enforce the agreement.

THE COURT: But you just told me a minute ago to do whatever was appropriate for the relief you were seeking. What relief were you seeking that you told Mr. Ely you wanted?

THE DEFENDANT: To have the Government finish the cooperation agreement so that I could be evaluated for substantial assistance. And there were also some outstanding issues regarding my continued safety while in custody as a result of the cooperation that had occurred thus far.

(Docket Entry No. 107, at 15-17).

Pinson learned of Ely's new job and new address in Washington, D.C. in approximately February 2009. Correspondence ensued. But Pinson's letters to Ely are not part of the record, and his testimony that he had asked Ely about the status of an appeal, as opposed to the status of his concerns about further debriefing with the government and about his facility assignment, is wholly unsupported.

Ely also testified. His testimony was consistent with, and supported by, the record. Ely stated that Pinson did not ask him to appeal in the phone conversation that occurred in late 2008 or early 2009. Pinson did not ask about an appeal in his written correspondence with Ely after that phone conversation. The record shows, and this court finds, that Pinson did not specifically ask Ely to file an appeal from the December 2008 judgment. Pinson's claim that Ely rendered ineffective assistance by failing to appeal fails.

VI. The Claim that the Government Violated the Plea and Cooperation Agreement

Pinson claims that the government violated the plea and cooperation agreement by failing to follow through on various promises. He alleges that the government cancelled the cooperation agreement, refused to sponsor Pinson for the WITSEC program, refused to move for a 5K1.1 adjustment, and directed government agents to seize Pinson's property in retaliation for Pinson's refusal to lie during an FBI debriefing.

The record does not support Pinson's claim that the government violated the plea agreement. At the sentencing hearing, the government agreed, on the record, that Pinson had cooperated and reserved the right to file a motion for reduction once, and should, the cooperation reach "substantial assistance" and the truthfulness of the information Pinson had provided was verified. The government explained the reasons that it was not asking for a downward departure based on substantial assistance:

AUSA: As to the other issues that Mr. Ely is referring to, there's a number of them in terms of the cooperation. I agree Mr. Pinson, as far as I can tell, he has certainly cooperated in the sense of sitting down and discussing with federal agents a number of these issues of drug usage, corrupt officials, etc., at Victorville. The agents tell me they don't have any reason to believe that he has not been truthful with them, but that has been relatively recent interviews. Those sorts of investigations take more time. I'm not prepared today to say that I'm ready to recommend a downward departure for substantial assistance because we can't determine whether, one, he has been truthful; and, two, truthfulness, if that's what it is, is going to result in assistance to the government. I'm certainly not opposed and would not oppose, if and when the time comes, that the agents tell me that, "Yes, Mr. Pinson's information was determined to be truthful and has resulted in additional cases, disciplinary procedures, or whatever against certain employees, other inmates", at that time a Rule 35 reduction may be appropriate. And if the agents tell me that it's appropriate, or if I determine it's appropriate from the information they give me, I have no qualm in either filing such a motion or agreeing to such a motion if it's filed by Mr. Pinson's attorneys, but I don't think we're there yet. So I'm not going to recommend a downward departure today.

(Docket Entry No. 82, at 22-23).

Fulfilling its agreement, the government asked the court to credit Pinson with acceptance of responsibility, to sentence Pinson at the bottom of the guideline level he scored, and to recommend to the BOP that Pinson be placed at the Coleman, Florida facility and receive a downward management adjustment. (Id., at 22-27). The government sent a "separation letter" the BOP to ensure that Pinson was not exposed to those against whom he cooperated. (Id., at 37). Pinson has failed to demonstrate that the government breached the plea and cooperation agreement.

Pinson's claims of prosecutorial misconduct - that the government encouraged Pinson to lie to the FBI and retaliated against him when he refused to do so - are wholly speculative and without support in the record. The government worked with defense counsel and the court to devise terms of confinement to recommend to the BOP that would benefit Pinson. Each of the property seizures Pinson identifies occurred because of a specific event that Pinson himself acknowledged, including a fire set by his cellmate and an altercation between Pinson and other inmates (in which, according to the record evidence, Pinson had attempted to stab another inmate with a homemade shank). Pinson has shown no basis for relief on this claim.

VII. Conclusion

Most of Pinson's claims, including that his plea and waivers of appellate and collateral challenge rights were involuntary, and the result of prosecutorial misconduct, are conclusively belied by the record. An evidentiary hearing on those issues is unnecessary. United States v. Samuels, 59 F.3d 526, 530 & n.16-17 (5th Cir. 1995) ("A hearing is not required under section 2255, however, if the motion, files, and record of the case conclusively show that no relief is appropriate." (citations omitted)). The evidentiary hearing held on the claim that Pinson directed his counsel to file a direct appeal showed that no such instruction was given. The evidentiary hearing defeated Pinson's ineffective assistance claim and his assertion that equitable tolling should apply to save his motion from the limitations bar. Pinson's 2255 motion and amended motion are denied. His civil action is dismissed, with prejudice. A final judgment is separately entered.

A certificate of appealability will not issue. Under AEDPA, a certificate of appealability is required for an appeal. "This is a jurisdictional prerequisite because the COA statute mandates that '[u]nless a circuit justice or judge issues a certificate of appealability, an appeal may not be taken to the court of appeals..." Miller-El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322, 336 (2003) (citing 28 U.S.C. 2253(c)(1)).

A certificate of appealability will not issue unless the petitioner makes "a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right." 28 U.S.C. 2253(c)(2). This requires a petitioner to demonstrate "that reasonable jurists would find the district court's assessment of the constitutional claims debatable or wrong." Tennard v. Dretke, 542 U.S. 274, 282 (2004) (quoting Slack v. McDaniel, 529 U.S. 473, 484 (2000)). A petitioner must show "that reasonable jurists could debate whether (or, for that matter, agree that) the petition should have been resolved in a different manner or that the issues presented were 'adequate to deserve encouragement to proceed further'." Miller-El, 537 U.S. at 336. If relief is denied on procedural grounds, the petitioner must show not only that "jurists of reason would find it debatable whether the petition states a valid claim of the denial of a constitutional right", but also that they "would find it debatable whether the district court was correct in its procedural ruling." Slack, 529 U.S. at 484. A district court may deny a certificate of appealability on its own, without requiring further briefing or argument. Alexander v. Johnson, 211 F.3d 895, 898 (5th Cir. 2000).

Pinson has failed to make the necessary showing for a certificate of appealability to issue.

SIGNED on December 28, 2012, at Houston, Texas.

Lee H. Rosenthal

United States District Judge

Other posts by this author

|

2014 mar 11

|

2014 mar 11

|

2014 mar 7

|

2014 mar 7

|

2013 nov 14

|

2013 nov 11

|

More... |

Replies