Transcription

①

SPECIAL REPORT

USA TODAY

THURSDAY, JULY 11, 2013

___________________________

THE COST OF

'life'

IN PRISON

America is facing this question: Should we pay $100,000 a year to house a sick, elderly inmate—or should society set him free?

[black-and-white photo of medicinal ward with an elderly man in a wheelchair facing camera]

PHOTOS BY H. DARR BELSER USA TODAY

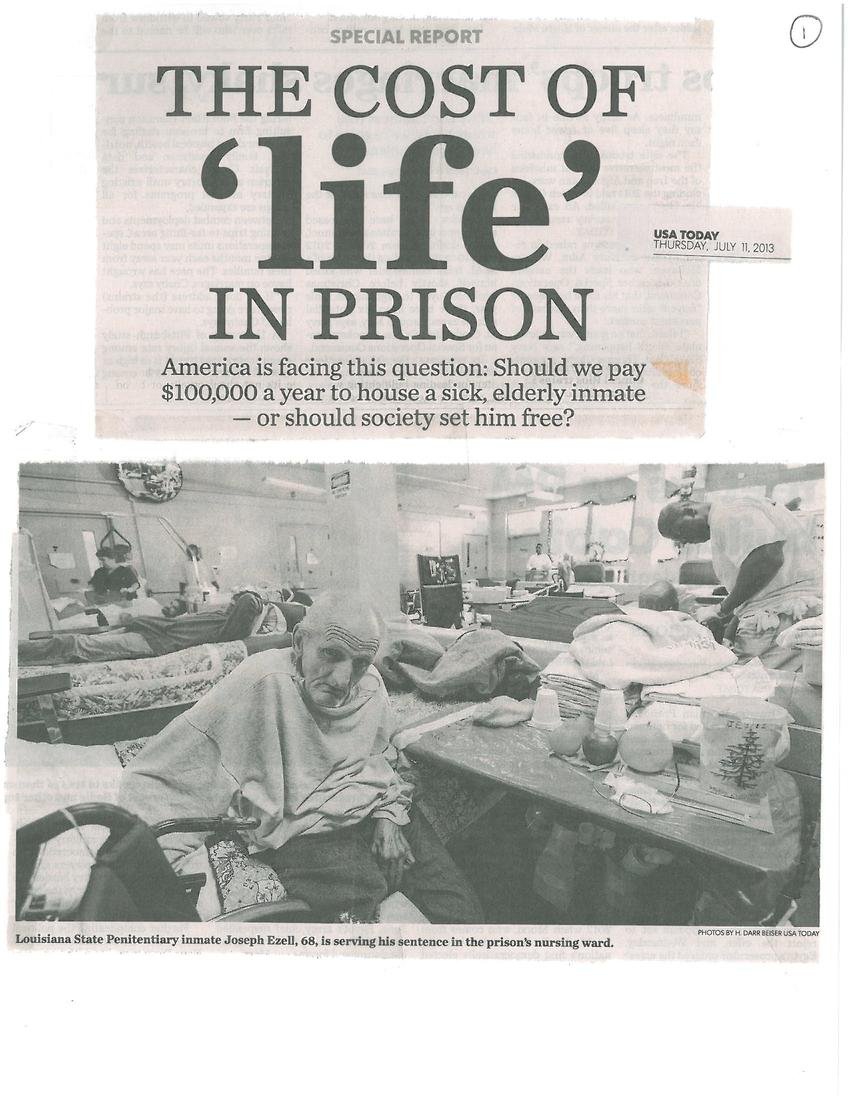

Louisiana State Penitentiary inmate Joseph Esell, 68, is serving his sentence in the prison's nursing ward.

ANGOLA, LA.

For decades, the Louisiana State Penitentiary has taken great pride in its vast farming operations, as well as its reputation as one of the toughest lockups in America.

The crops and cattle raised by prisoners on the remote 18,000 acres ringed by razor wire have long gone to feed Angola's 5,000 inmates, with enough left over to stock the novelty hot sauce and jelly products sold in the prison museum.

[black-and-white photo of elderly man]

Warden Cain

Yet Warden Burl Cain said something on "the farm" that threatens the bounty it reaps every year.

Aging, sick and disabled prisoners are seriously limiting the numbers that can be deployed to tend the land. Of the 1,000 who typically work the fields, Cain said he's lucky if 600 to 700 are physically able to do the job. After all, a third of all inmates are older than 50, and many are so debilitated that the state spends north of $100,000 per inmate to care for them.

"This place was not built to accommodate people like this," Cain said. "I'm telling you, we're really feeling it."

So are the rest of America's vast, aging prison populations.

The fiscal, legal, social, and political challenges of housing this country's graying inmates have arrived with full force at precisely the time when states, and the federal government, are looking to rein in spending. A problem swelling for decades has become "a national epidemic," according to a 2012 report by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Yet efforts to address an issue that will only worsen with time have largely floundered, ensuring that even incapacitated inmates ridden with tumors or paralyzed by Parkinson's disease live their last days in prison hospitals. The enormous medical costs required to maintain this status quo will inevitably sap money from other areas of government that affect residents who will never set foot near these penitentiaries.

FEW EARLY RELEASES

Nearly a quarter-million inmates in state and federal prisons—enough to fill the Rose Bowl nearly three times—are classified as "elderly" or "aging," according to the ACLU report. The designation applies to inmates age 50 and older whose aging process, according to the National Institute of Corrections, is often accelerated by general poor health before entering prison and the stress of confinement once there.

At least 15% of the prisoners in 20 states are 50 or older, according to the ACLU report. In West Virginia, 20% were at least 50. The costs of confining such prisoners are about double —$68,270 per year— the $34,135 annual cost for the average younger inmate.

Although at least 15 states and the District of Columbia have some provision for the early release of geriatric inmates, a 2010 study by the Vera Institute of Justice funded by the Pew Center on the States found that authorities rarely used the exceptions because of "political considerations" related to public safety policy and a lengthy review process.

To accommodate the number of aging and disabled, Connecticut officials won approval in March to begin transferring some offenders to a privately run nursing home.

Last month, California prison officials announced the dedication of an $839 million complex in Stockton to provide "mental health and medical services to the state's sickest inmate patients."

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokesman Jeffery Callison said the first of the 1,722 inmate-patients will begin arriving this month.

The facilities are the result of a legal fight in the federal courts over the quality of health care in the state's 33 prisons. The charges were prompted by lawsuits, filed more than a decade ago, alleging substandard medical and mental health treatment.

Secretary of Corrections and Rehabilitation Jeff Beard said in a statement that the 54-building complex on 200 acres helps show that "we are serious about health and well-being of inmates entrusted to us."

Groups advocating for reductions in prisons said the facility represented a failure of state officials to address its problems years ago.

"If the state had taken common sense steps to parole the elderly, the terminally ill, the mentally disabled, would this prison hospital have been built?" said Mary Sutton, a spokeswoman for Critical Resistance.

A NATIONAL PRIORITY

Each year, the Justice Departments's inspector general ranks the agency's "top management challenges." And each year since 2006, the federal prison system's growing and aging prison population has ranked among such urgent priorities as safeguarding national security and enhancing the nation's cyber-security defenses.

"Housing a continually growing and aging population of federal inmates and detainees is consuming an ever-larger portion of the department's budget," the inspector general's 2012 report said, adding that the burden is "making safe and secure incarceration increasingly difficult to provide and threatening to force significant budgetary and programmatic cuts to other (Justice) components in the near future."

Since 2006, the number of inmates has grown nearly 14% to about 220,000. Of all the corrections systems in the nation, the U.S. Bureau of Prisons (BOP) houses the third-largest number of offenders who are 50 or older, according to numbers compiled by the ACLU.

"We are on an unsustainable path here," Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz said in an interview with USA TODAY.

In April Horowitz highlighted that concern in a scathing review of the federal system, concluding that the program allowing for the early release of offenders with terminal illnesses or other debilitating conditions was so "poorly managed" that some inmates languished and died before their release requests were acted on by prison authorities.

Inmates who qualify for discharge under the program could be released to the care of family members at home or in facilities where some would probably qualify as public assistance. But of 208 cases reviewed by the inspector general from 2006 to 2011 in which inmate requests for so-called compassionate release had been approved by lower-level Bureau of Prisons officials, 28 offenders died while awaiting final action.

In one case, an inmate's request in 2006 for early release was denied even though the offender had suffered a massive stroke and was in a "near vegetative state."

The inmate, serving a life sentence for cocaine and heroin distribution, required a feeding tube, bathing, bedpan and repositioning every two hours to avoid bed sores.

Though he had "no hope for recover," Justice officials rejected a recommendation for early release because his life expectancy could not be determined.

The inmate remains in prison. Though his condition has improved somewhat, the entire right side of his body is paralyzed, and medical authorities say he cannot speak and "needs total assistance with his activities in daily living."

In addition, Horowitz's report determined that the BOP did not track the costs related to caring for aging and sick inmates who may be eligible for release.

"You would think you would want to know what the potential cost savings (related to the early release of ill inmates) would be," Horowitz said.

The cost information that the agency did track showed that the BOP paid $28,893 per year to house the average inmate, while it cost $57,962 per year for each inmate housed at one of its medical centers. Costs at the BOP medical centers increased 38% from 2006 to 2011. By the end of last year, 7,464 inmates were in federal prison medical facilities.

Under provisions for required spending reductions within the federal government, $1.6 billion was cut from the budge of the Justice Department, which manages the BOP. The cuts so threatened the operations of the BOP that Attorney General Eric Holder authorized the transfer of $150 million in other funds in March to avoid the furloughs of thousands of staffers.

$100,000 PER INMATE

Of the more than 5,000 prisoners housed at Angola, 34% are at least 50 or older. Among the 10 age groups tracked by prison officials, the largest number of offenders in any one category—859—are 55 to 64 years old.

Assistant Warden Cathy Fontenot said the prison houses about 130 offenders whose annual medical costs exceed $100,000 per inmate.

The costs are associated with treating some of the same and most serious conditions that exist in the free world: cancer, HIV, hemophilia, liver disease, and chronic renal failure.

Some of the sickest and oldest of Angola's residents are housed in the prison hospice unit where the staff includes fellow inmates who provide the constant care required.

Jimmy Johnston, 71, serving a life sentence for second-degree murder, has bone cancer and occupies one of the beds in the large, busy open ward. A resident of Angola since his conviction in 1978, Johnston has been treated for tumors on his spine and head. He has endured chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

His prognosis is not good.

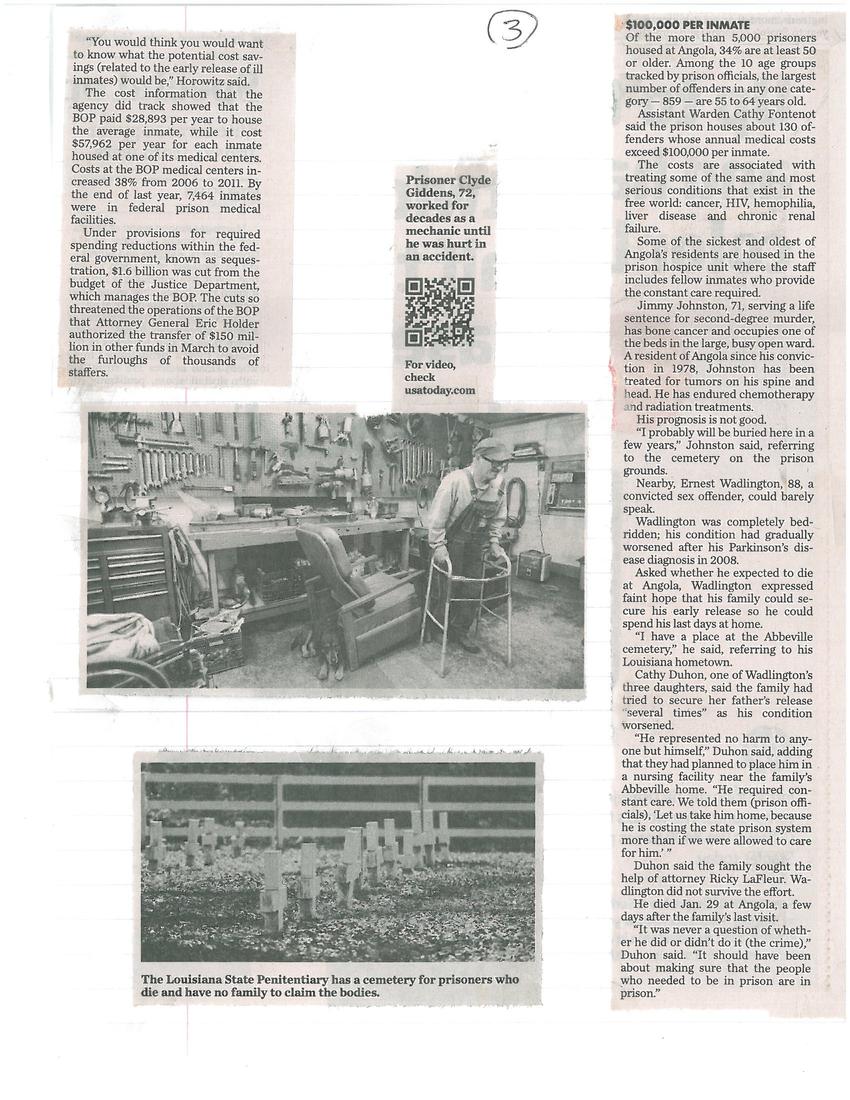

"I probably will be buried here in a few years," Johnston said, referring to the cemetery on the prison grounds.

Nearby, Ernest Wadlington, 88, a convicted sex offender, could barely speak.

Wadlington was completely bedridden: his condition had gradually worsened after his Parkinson's disease diagnosis in 2008.

Asked whether he expected to die at Angola, Wadlington expressed faint hope that his family could secure his early release so he could spend his last days at home.

"I have a place at the Abbeville cemetery," he said, referring to his Louisiana hometown.

Cathy Duhon, one of Wadlington's three daughters, said the family had tried to secure her father's release "several times" as his condition worsened.

"He represented no harm to anyone but himself," Duhon said, adding that they had planned to place him in a nursing facility near the family's Abbeville home. "He required constant care. We told them (prison officials), 'Let us take him home, because he is costing the state prison system more than if we were allowed to care for him.'"

Duhon said the family sought the help of attorney Rick LaFluer. Wadlington did not survive the effort.

He died Jan. 29 at Angola, a few days after his family's last visit.

"It was never a question of whether he did or didn't do it (the crime)," Duhon said. "It should have been about making sure that the people who needed to be in prison are in prison."

[black-and-white photo of elderly man using walker]

Prisoner Clyde Giddens, 72, worked for decades as a mechanic until he was hurt in an accident.

[QR code clipping]

For video, check usatoday.com

[black-and-white photo of small cemetery]

The Louisiana State Penitentiary has a cemetery for prisoners who die and have no family to claim the bodies.

Other posts by this author

|

2024 may 17

|

2024 may 14

|

2024 feb 27

|

2024 jan 23

|

2023 sep 2

|

2022 aug 4

|

More... |

Replies