Transcription

PRISON LAW OFFICE

General Delivery, San Quentin, CA 94964

Telephone (510) 280-2621 . Fax (510) 280-2704

www.prisonlaw.com

Director:

Donald Specter

Managing Attorney:

Sara Norman

Staff Attorneys:

Mae Ackerman-Brimberg

Rana Anabtawi

Steven Fama

Alison Hardy

Sia Henry

Corene Kendrick

Rita Lomio

Margot Mendelson

Millard Murphy

Lynn Wu

Your Responsibility When Using the Information Provided Below:

When putting this material together, we did our best to give you useful and accurate information because we know that prisoners often have trouble getting legal information and we cannot give specific advice to all prisoners who ask for it. The laws change often and can be looked at in different ways. We do not always have the resources to make changes to this material every time the law changes. If you use this pamphlet, it is your responsibility to make sure that the law has not changed and still applies to your situation. Most of the materials you need should be available in your institution's law library.

INFORMATION RE: ELDERLY PRISONER PAROLE

November 21, 2012 (January 2015)

We have received your request for information about new California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) policies regarding parole of elderly prisoners. We apologize for sending this form letter, but we are unable to provide individual responses to everyone who seeks our help. We hope that this letter will answer your questions.

On February 10, 2014, the three-judge court overseeing the California prison overcrowding class action case (Plata/Coleman v. Brown) issued an order that, among other things, requires the State to put in place a new parole process so that prisoners who are 60 years of ago or older and have been incarcerated at least 25 years on their current sentence will be referred to the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) to determine suitability for parole.

The new Elderly Parole Program applies to prisoners serving indeterminate (life with the possibility of parole) terms and prisoners serving determinate (set length) term. It does not apply to prisoners serving death or life without the possibility of parole (LWOP) terms. Attached to this letter is a June 16, 2014, BPH memorandum which gives an overview of the program. The BPH has told the three-judge court that as of December 31, 2014, it had granted parole to 115 prisoners eligible for elderly parole.

The same general procedures and legal standards that apply to regular lifer parole suitability hearings apply to the Elderly Parole Program. This means the BPH may deny parole if an elderly prisoner's release would pose an unreasonable risk to danger to public safety. However, for all Elderly Parole Program hearings, the BPH risk assessments will consider how age and physical condition reduce elderly prisoners' risk of future violence.

Board of Directors

Penelope Cooper, President . Michele WalkinHawk, Vice President

Marshall Krause, Treasurer . Christiane Hipps . Margaret Johns

Cesar Lagleva . Laura Magnani . Michael Marcum . Ruth Morgan . Seth Morris

Elderly Parole Program for Lifers (Prisoners Serving Indeterminate Terms)

Lifers who are 60 years or older and have been incarcerated 25 years or more on their current sentence, and who have not yet had an initial parole suitability hearing, will be referred by the CDCR to the BPH and scheduled for an Elderly Parole Program suitability hearing.

Lifers who are 60 years or older and have been incarcerated 25 years or more on their current term, and who have been denied parole at the initial suitability hearing will be considered for elder parole at their next regularly scheduled parole hearing under the Elderly Parole Program. The BPH will give scheduling priority to those prisoners who are most likely to be found suitable for parole, with the length of the most recent denial being used as one factor to determine likelihood of suitability.

The BPH says it has been and will review all 3-year denials annually to determine if a more prompt parole consideration hearing should be scheduled. During that annual review, BPH will consider whether the prisoner meets the elder parole eligibility criteria and if so whether to schedule a hearing sooner than is already scheduled.

Any lifer who eligible for elderly parole, including those with lengthier (for example, five, ten, or fifteen year) denial periods, can file a petition with the BPH asking that their hearing be advanced because they meet the eligibility criteria for elder parole. The BPH will accept petitions from elderly prisoners even if it has been less that three years since the prisoner last filed a hearing advancement petition, but because only one such advancement petition is allowed every three years, the BPH decision will be made based on its own review of the prisoner's situation, not on the petition.

The same general procedures and legal standards that apply to regular lifer parole suitability hearings will apply when an elder parole is an issue. This means the BPH may deny parole if an elderly prisoner's release would pose an unreasonable risk of danger to public safety. However, for all Elderly Parole Program hearings, the BPH risk assessments will consider how age, time served, and diminished physical condition, if any, reduce elderly prisoners' risk for future violence.

Lifers who are found suitable under the Elderly Parole program is not being fairly applied to you, please write us. We will read your letter and consider whether we can help.

Prison Law Office

Elderly Parole (January 2015)

page 3

Elderly Parole Program for Determinate-Term Prisoners

The BPH will also hold Elderly Parole Program suitability hearings for determinate-term prisoners who are 60 years or older and have served 25 years or more on their current term. These hearings will start in February 2015. BPH will hold a parole consideration hearing for eligible determinate term prisoners within one year of the prisoner becoming eligible (that is, one year from the date the prisoner is both age 60 or older and has also served 25 years on his or her current term).

The same general procedures and legal standards that apply to regular lifer parole suitability hearings will apply when a determinate term prisoner has an elder parole hearing. This means the BPH may deny parole if an elderly prisoner's release would pose an unreasonable risk of danger to public safety. However, the BPH risk assessment done the hearing will consider how age, time served, and diminished physical condition, if any, reduce an elderly prisoner's risk for future violence.

Determinate term prisoners who are found suitable under the Elderly Parole program will be released when the parole grant becomes final (after review by the full BPH), even if that date is before the date the prisoner would have been otherwise released.

If you are a determinate term prisoner who is eligible for elder parole, and think the elder parole program is not being fairly applied to you, please write us. We will read your letter and consider whether we can help.

*******

If you want more information about the parole consideration process in general or about how to file a state court petition for writ of habeas corpus, please write back to the Prison Law Office to request free information packets on those topics. Some information is also available on the Resources page of the Prison Law Office website at www.prisonlaw.com.

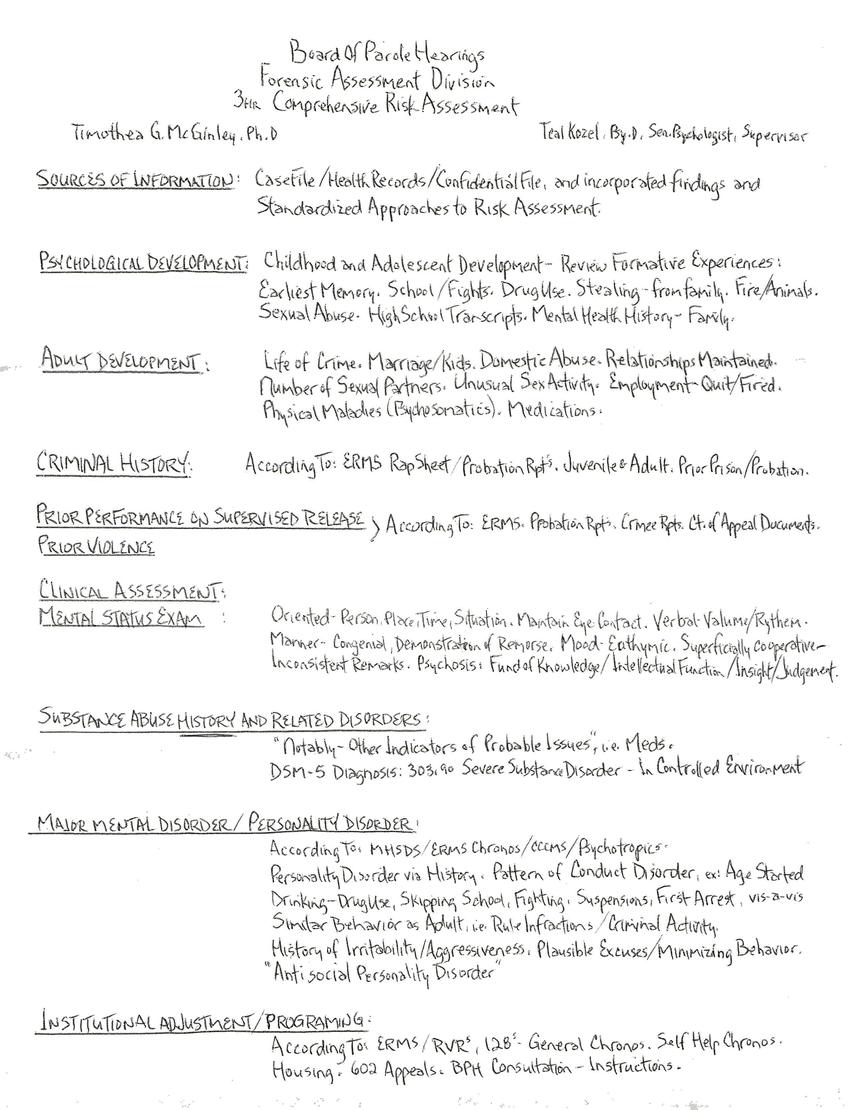

Board of Parole Hearings

Forensic Assessment Division

3HR Comprehensive Risk Assessment

Timothea G. McGinley. Ph.D

Teal Kozel By. D. Sen. Psychologist, Supervisor

SOURCES OF INFORMATION: Case File/Health Records/Confidential File, and incorporated findings are Standardized Approaches to Risk Assessment.

PSYCHOLOGICAL DEVELOPEMENT: Childhood and Adolescent Development - Review Formative Experiences: Earliest Memory. School/Fights. Drug Use. Stealing - from family. Fire/Animals. Sexual Abuse. High School Transcripts. Mental Health History - Family.

ADULT DEVELOPMENT: Life of Crime. Marriage/Kids. Domestic Abuse. Relationships Maintained. Number of Sexual Partners. Unusual Sex Activity. Employment - Quit/Friend. Physical Maladies (Psychosomatics). Medications.

CRIMINAL HISTORY: According To: ERMS Rap Sheet/Probation Rpt's. Juvenile & Adult. Prior Prison/Probation.

PRIOR PERFORMANCE ON SUPERVISED RELEASE PRIOR VIOLENCE: According To: ERMS. Probation Rpt's. Crime Rpts. Ct. of Appeal Documents.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT:

MENTAL STATUS EXAM: Oriented-Person. Place. Time. Situation. Maintain Eye Contact. Verbal-Volume/Rhythm. Manner-Congenial, Demonstration of Remorse. Mood-Euthymic. Superficially cooperative-Inconsistent Remarks. Psychosis: Fund of Knowledge/Intellectual Function/Insight/Judgement.

SUBSTANCE ABUSE HISTORY AND RELATED DISORDERS: "Notably-Other Indicators of Probable Issues", i.e. Meds.

DSM-5 Diagnosis: 303:90 Severe Substance Disorder - In Controlled Environment

MAJOR MENTAL DISORDER/PERSONALITY DISORDER: According To: MHSDS/ERMS Chronos/CCCMS/Psychotropics.

Personality Disorder via History. Pattern of Conduct Disorder, ex: Age Started Drinking - Drug Use, Skipping School, Fighting, Suspensions, First Arrest, vis-à-vis Similar Behavior as Adult, i.e. Rule Infractions/Criminal Activity.

History of Irritability/Aggressiveness. Plausible Excuses/Minimizing Behavior.

"Anti Social Personality Disorder"

INSTITUTIONAL ADJUSTMENT/PROGRAMING:

According To: ERMS/RVRs, 128s - General Chronos. Self Help Chronos. Housing. 602 Appeals. BPH Consultation - Instructions.

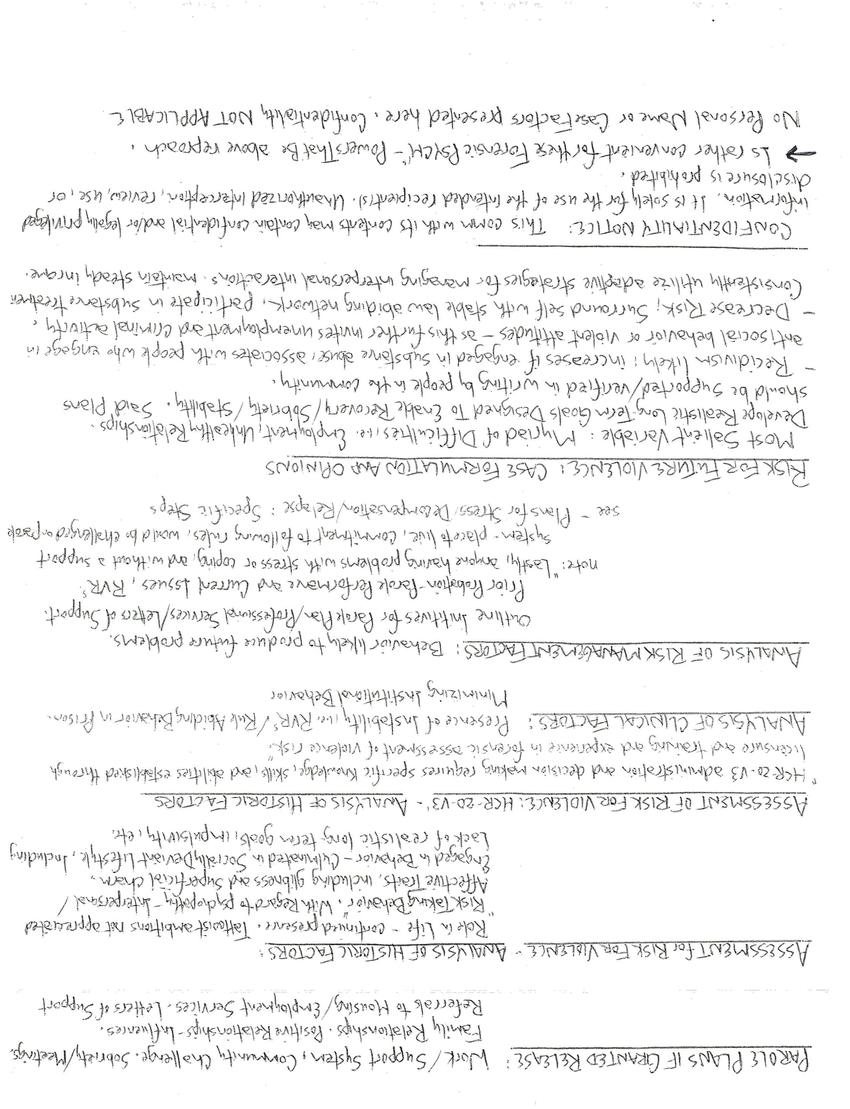

[unable to type next page - upside down]

J. Hum. Rights. Soc. Work (2016) 1:165-174

DOI 10.1007/s41134-016-0021-0

Analysis of US Compassionate and Geriatric Release Laws: Applying a Human Rights Framework to Global Prison Health

Tina Maschi 1. George Leibowitz 2. Joanne Rees 3. Lauren Pappacena 1.

Published online: 4 November 2016

(C) Springer International Publishing 2016

Abstract The purpose of this paper was to analyse the compassionate and geriatric release laws in the USA and the role of advanced age and/or illness. In order to identify existing state and federal laws, a search of the LexisNexis legal date-base was conducted. Keyword search terms were used: compassionate release, medical parole, geriatric prison release, elderly (or seriously ill), and prison. A content analysis of 47 identified federal and state laws was conducted using inductive and deductive analysis strategies. Of the possible 52 federal and state corrections systems (50 states, Washington D.C., and Federal Corrections), 47 laws for incarcerated people, or their families, to petition for early release based on advanced age or health were found. Six major categories of these laws were identified: (1) physical/mental health, (2) age, (3) pathway to release decision, (4) post-release support, (5) nature of the crime (personal and criminal justice history), and (6) stage of review. Recommendations are offered, for increasing social work policy and practice expertise, and advancing the rights and needs of this population in the context of promoting human rights, aging, health, and criminal justice reform.

Keywords Older adults . Criminal justice . Compassionate and geriatric release laws . Content analysis . Human rights . Social work . Forensic social work

Tina Maschi

tmaschi@fordham.edu

1 Graduate School of Social Service, The Justia Agenda, Fordham University, New York, NY, USA

2 School of Social Welfare, Stony Brook University, State University of New York, Stony Brook, USA

3 Department of Social Work, Long Island University, Brooklyn, USA

Introduction

Correctional systems across the globe are struggling with managing the rapidly growing aging and seriously ill population. In the USA, approximately 200,000 adults aged 55 and above are behind bars, many of which have a complex array of health, social service, and legal needs that all too often go unaddressed prior to and after their release from prison (Human Rights Watch [HRW] 2012). The large number of older people in prison is partially attributed to the passage of stricter sentencing laws, such as "Three Strikes You're Out" and the subsequent mandatory longer prison terms (American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU] 2012). These restrictive policies have created a human-made disaster in which many sentenced to long-term prison sentences will reach old age while in prison or shortly after their release. Social work, interdisciplinary scholars, and human rights advocates view the current crisis as a human rights issue that impact the rights and needs of the aging and seriously ill population (Byock 2002; HRW 2012).

Compassionate and Geriatric Release Laws

Beginning in the 1970s, there has been a growing awareness among lawmakers and other professionals, especially in the USA, of the need for compassionate and geriatric policies to address the growing aging and health crisis in prisons. Currently, medical parole and compassionate release laws, and programs for mostly nonviolent, terminally ill incarcerated people have been implemented in an effort to transition aging and/or serious or terminally ill incarcerated people to community-based care (Chiu 2010; Williams et al. 2011). Most of the social work and interdisciplinary scholarly literature in law and medicine in the USA has focused on compassionate release laws (Ferri 2013; Jefferson-Bullock 2015; Green 2014; William et al. 2011). The authors of these journal articles describe the legal/ethical practice and financial dilemmas posed when incarcerating older and seriously ill people. These authors acknowledge that, in theory, the release of persons with serious and/or terminal illness from prison to the community is cost-effective. However, there are difficulties noted in their implementation including bureaucratic red tape and negative public attitudes toward more compassionate approaches to criminal justice (Coleman 2003; Ferri 2013; Jefferson-Bullock 2015; Kinsella 2004; Green 2014; William et al. 2011).

To date, there has not been comprehensive human rights-based analysis of both the compassionate and geriatric release laws in the USA. The USA is a compelling case study because it has the largest population of adults aged 50 and older (N=200,000; ACLU 2012) behind bars. Additionally, the USA has 50 states in which laws vary by provisions based on a variety of eligibility factors including age, physical and mental health, and legal status. Therefore, the purpose of this content analysis of the US compassionate and geriatric release laws was to compare the provisions of current laws and to evaluate the extent to which these were consistent with human rights guidelines. This review was guided by the following research questions: (1) What are the characteristics of compassionate and geriatric release laws in the USA? And (2) to what extent are existing compassionate and geriatric release laws consistent with core principles of a human rights framework? As detailed in the discussion section, the results of this review have implications for social work and human rights for improving social work and interdisciplinary and intersectoral responses to the treatment of criminal justice involved aging and serious and terminally ill people (Anno et al. 2004).

Applying a Human Rights Framework

Applying a human rights framework to the laws, policies, and practices with aging and seriously ill people in prison can be used to assess the extent to which these laws meet basic human rights principles. In particular, the principles of a human rights framework can provide assessment guidelines for developing or evaluating existing public health and criminal justice laws or policies, such as USA compassionate and geriatric release laws. The underlying values/principles of a human rights framework include dignity and respect for all persons, and the indivisible and interlocking holistic relationship of all human rights in civil, political, economic, social, and cultural domains (UN 1948). Additional principles include participation (especially with key stakeholder input on legal decision-making), non-discrimination (i.e., laws and practices in which individuals are not discriminated against based on differences, such as age, race, gender, and legal history), transparency, and accountability (especially for government transparency and accountability with their citizens; Maschi 2016).

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) also is an instrument that provides assistance with determining the most salient human rights issues affected. Ratified in 1948 as a response to the atrocities of World War II, the UDHR was voted in favour of by 48 countries, including the USA (UN 1948). It provides the philosophical underpinnings and relevant articles to guide policy and practice responses to the aging and serious and terminally ill in prison. The UDHR preamble underscores the norm of "respect for the inherent dignity and equal and inalienable rights" of all human beings. This is of fundamental importance to crafting the treatment and release of aging and seriously ill persons in prison.

There are several UDHR articles that are important to consider when providing a rationale and response to the aging and seriously ill population in prison. For example, Article 3 states, "Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and the security of person." Article 5 states, "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment." Article 6 states, "Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law." Article 8 states "Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law," and Article 25 states, "Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food and clothing" (UN 1948, p. 3-7).

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC 2009) Special Needs Handbook also offers additional guidelines to assess policy and practice responses to the aging and/or seriously and terminally ill in prison. According the UNOCD (2009), older prisoners, including those with mental and physical disabilities, and terminal illnesses are a special needs population and as such are to be given special health, social, and economic practice and policy considerations (UNODC 2009). The handbook also addresses the issue of age in corrections. It is of note that the age at which individuals are defined as "older" or "elderly" in the community often differs from the definition of elderly applied in corrections. Globally, many social welfare systems, including the USA's, commonly view adults as older when they reach the age of 65 because that is when most individuals are eligible to receive full pension or social security benefits. However, although it varies among states, incarcerated persons in the USA may be classified as "older adult" or "elderly" as young as age 50 (HRW 2012; UNODC 2009).

Study Significance

The results of this review also have important implications for global social service, health and correctional systems, and policymaking bodies. While these findings may not generalize globally, conducting a comparative analysis of the regional laws of one country, such as the USA, may be useful for developing or refining existing laws internationally. This information also can be used by social workers to collaborate with correctional and community service providers. In particular, forensic social workers, especially those who are trained in case management, can play an important role in facilitating the release process and smooth care transitions of aging and seriously ill people released from prison (Office of the Inspector General, 2016). Local and global policy makers, including social workers, also can use these findings to craft more human rights responsive laws and policies that affect this vulnerable population.

Methods

In order to identify all of the compassionate and geriatric release laws in the USA, the research term conducted a comprehensive search of the LexisNexis legal database. The following key word search terms were used: compassionate release, medical parole, geriatric prison release, elderly (or seriously ill), and prison. Identified laws were included in the sample if they met the following criteria: (1) identified aging or seriously ill people in prison and (2) were a law or policy regarding early release from prison based on age or health status. Two trained research assistants reviewed the laws and coded the data. The term met weekly for a 6-month period with the lead researcher until 100% consensus was reached for all categories of data extracted. The search located 52 federal and state corrections systems (50 states, Washington DC, and Federal Corrections). Of the 52, 47 were found to have a law for incarcerated people or a family member (or surrogate) to petition for early release based on advanced age or health. There was no evidence of any applicable law or provision found in five states (i.e., Illinois, Massachusetts, South Caroline, South Dakota, and Utah).

Data Analysis Methods

Interpretive content analysis strategies as outline by Drisko and Maschi (2016) were used to analyse the compassionate and geriatric release laws form the USA. Interpretive content analysis is a systematic procedure that codes and analyses qualitative data, such as the content of published articles or legal laws. A combination of deductive and inductive approaches can be used, and this strategy was used in the current review. Deductive analysis strategies were used to extract the data by constructing pre-existing categories or the criteria commonly found in compassionate and geriatric release laws (e.g., age, physical and mental health status, nature of crime). For each category, counts of state and federal laws were then calculated for frequencies and percentages of each category (e.g., 13 states had laws with age provisions).

Inductive analysis strategies were used to analyse any emerging or new categories that could not be classified in existing categories. Tutty and colleagues' (1996) four-step qualitative data analysis strategies were utilized to analyse this data. Step 1 involved identifying "meaning units" (or in-vivo codes) from the data. For example, the assignment of meaning units included the assigning codes. In step 2, second-level coding and first-level meaning units were sorted and placed in their emergent categories. Meaning unit codes were arranged by clustering similar codes into a category and separating dissimilar codes into separate categories. The data were then analysed for relationships, themes, and patterns. In step 3, the categories were examined for meaning and interpretation. In step 4, conceptually clustered matrices, or tables, were constructed to illustrate the patterns and themes found in the data, including characteristics of the principles of a human rights framework (Miles and Huberman 1994).

Summary of Findings

Out of 50 states plus Washington, DC, and a Federal Law (totalling 52 jurisdictions), 47 jurisdictions including Washington, DC, and the Federal Government were found to have compassionate or geriatric release laws. Five states did not have any publicly available records of compassionate or geriatric release laws (i.e., IL, MA, SC, SD, and UT). After review of the laws from these 47 legal systems in the USA (45 separate US States and D.C., as well as one federal law), basic structural consistencies were found that impacted the determination for early release or furlough from prisons based on physical or mental incapacity or advanced age. Six categories of compassionate and geriatric release laws identified were (1) physical/mental health status, (2) age, (3) nature of crime (i.e., personal and criminal justice history or risk level), (4) pathway to release decision, (5) post-release support, and (6) stage of review (i.e., initial ground-level investigation for a release petition).

Other posts by this author

|

2023 may 31

|

2023 apr 5

|

2023 mar 19

|

2023 mar 5

|

2023 mar 5

|

2023 mar 5

|

More... |

Replies