Transcription

[Text highlighted in yellow by William Goehler is indicated with an asterisk (*) on either side.]

[written in black pen:]

BTB

Individuals appreciate all data available for consideration in making up their mind about the arbitrary realities extant in their zone of responsibility

Fiat Lux

[a newspaper clipping:]

From Cops and Cages to Resources and Repair: The '94 Crime Bill and the Need for a People's Process

By Kamau Butcher, Kira Shepherd, Erica Perry, and Marbre Stahly-Butts

This September marks the 27th anniversary of the 1994 Crime Bill's passage, one of the most harmful pieces of legislation in modern US history. The flaws within the bill are both substantive and procedural—drafted by then Senator now US president *Joe Biden* in collaboration with police union leadership and without any substantive input or participation from the communities it would devastate. As the movement to divest from policing and cages gains momentum, it's vital that we change our investments to keep our communities safe, as well as the processes by which we decide how to allocate resources. The People's Coalition for Safety and Freedom (PCSF) is working to repeal and replace the Crime Bill with a community investment bill of our own, because we can't rely on the architects of our oppression to legislate us out of it. We must take the reins to create the safety we deserve.

The Politics of Anti-Blackness and the Creation of the Crime Bill

Throughout the 1960s-1980s, shifting racial demographics of cities across the country were the backdrop for increasingly neoconservative policies of city governance and the 'tough on crime' approaches to community safety that followed. As sever community divestment and austerity budgets ravaged communities of color, these communities raised concerns over safety that stemmed from lack of resources and opportunity. The scope of policing and its impact on the public's perception of safety also expanded substantially during this time. The broken windows theory influenced a policing institution that maintained racist views of Black people as inherently "criminal." These views informed the federal government's push for punitive measures to surveil and control criminalized neighborhoods and communities.

By the time the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (aka "the Crime Bill") was drafted, law enforcement leadership had established dual roles of defining and maintaining "safety." Joe Biden, then Chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, built a relationship with Tom Scotto, then president of the National Association of Police Organizations. At the time, the National Association of Police Organizations represented about 220,000 police department employees across the country. Biden worked closely with Scotto to draft the Senate version of the bill, with Scotto's initial demands centered around funding for 100,000 new police. Biden, Scotto, and law enforcement leadership knew then that expanding the police force would subsequently require more jails and prisons to imprison the people who would be stopped, profiled, and policed by these new cops. Clearly, both Biden and the police understood the true function of policing: filling cages.

When the bill was introduced, the core disagreement between advocates on either side did not lie in impact of the bill but in whether these were desirable impacts. An alert distributed by the Center for Constitutional Rights in 1994 warned that "the full impact of the Senate Crime Bill on the lives of poor people, people of color, immigrants, and children is shocking. It will execute or lock-up more people for longer periods of time, disregarding Constitutional protections, without having any appreciable effect on crime in our society."

Community members, legal advocates, and civil rights organizations had the foresight to understand how a bill collaboratively drafted with law enforcement would harm their communi-

Continued on next page

[a printed page:]

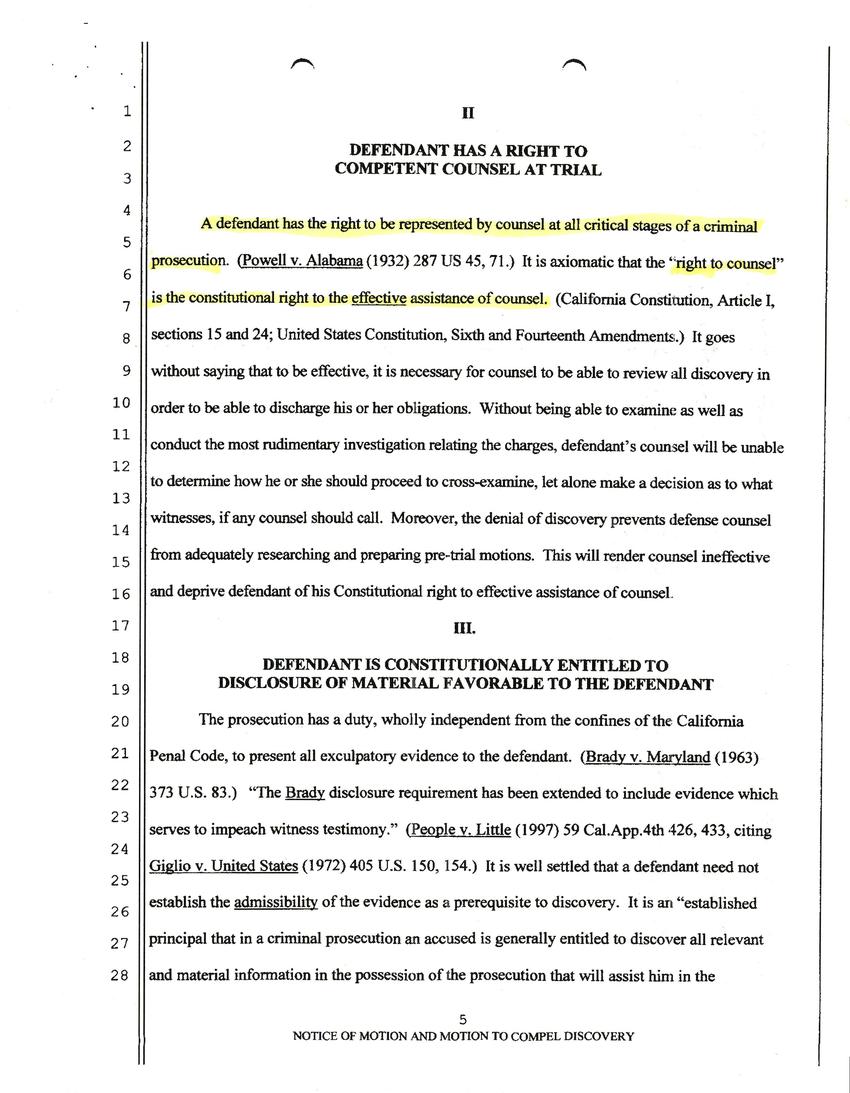

II

DEFENDANT HAS A RIGHT TO COMPETENT COUNSEL AT TRIAL

*A defendant has the right to be represented by counsel at all critical stages of a criminal prosecution.* (Powell v. Alabama (1932) 287 US 45, 71.) It is axiomatic that the *"right to counsel" is the constitutional right to the effective assistance of counsel.* (California Constitution, Article I, sections 15 and 24; United States Constitution, Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.) It goes without saying that to be effective, it is necessary for counsel to be able to review all discovery in order to be able to discharge his or her obligations. Without being able to examine as well as conduct the most rudimentary investigation relating the charges, defendant's counsel will be unable to determine how he or she should proceed to cross-examine, let alone make a decision as to what witnesses, if any counsel should call. Moreover, the denial of discovery prevents defense counsel from adequately researching and preparing pre-trial motions. This will render counsel ineffective and deprive defendant of his Constitutional right to effective assistance of counsel.

III

DEFENDANT IS CONSTITUTIONALLY ENTITLED TO DISCLOSURE OF MATERIAL FAVORABLE TO THE DEFENDANT

The prosecution has a duty, wholly independent from the confines of the California Penal Code, to present all exculpatory evidence to the defendant. (Brady v. Maryland (1963) 373 U.S. 83.) "The Brady disclosure requirement has been extended to include evidence which serves to impeach witness testimony." (People v. Little (1997) 59 Cal.App.4th 426, 433, citing Giglio v. United States (1972) 405 U.S. 150, 154.) It is well settled that a defendant need not establish the admissibility of the evidence as a prerequisite to discovery. It is an "established principal that in a criminal prosecution an accused is generally entitled to discover all relevant and material information in the possession of the prosecution that will assist him in the

5

NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION TO COMPEL DISCOVERY

[more newspaper clippings, continuing from previous:]

ties. Joe Biden and Democratic leadership rejected that foresight. During a 1993 Senate floor speech, Biden proclaimed that he was "not one of these wacko liberals who only want to look at the causes" when addressing community safety. He went on to say: "It doesn't matter whether or not they were deprived as a youth. It doesn't matter whether or not they had no background that enabled them to become socialized into the fabric of society. It doesn't matter whether or not they're the victims of society. I don't want to ask, 'What made them do this?' They must be taken off the street."

KEY COMPONENTS OF THE CRIME BILL

The Crime Bill has numerous harmful components, including expansion of mandatory minimum sentencing and the Community Oriented Policing Services, or "COPS" Program, explored more below. In order to more clearly reveal the link between policing and imprisonment, and how specifically the Crime Bill expanded both, we highlight a few lesser-known yet devastating pieces of the bill: Three strikes laws, gang enhancements, and immigration.

The Crime Bill enacted a slew of three strike laws, which force an automatic life sentence upon someone who is convicted of certain felonies if this person's record already contains two convictions. These laws are especially harmful to Black and Brown people, since racist laws and inequitable enforcement have resulted in increased arrests and convictions in communities of color. Moreover, shortly after the Crime Bill was introduced, dozens of states enacted three strike laws of their own to meet the conditions for increased federal subsidies. This increased incarceration rates of Black and Brown people substantially in certain states. For example, close to half of the people incarcerated for life under California's three strikes provision are Black.

Additionally, the Crime Bill asserted that someone deemed to be involved in a "criminal street gang" can have an additional ten years added to their prison sentence. Unsurprisingly, the Crime Bill's definition of 'gang' is so broad that a prosecutor could easily tack up to a decade onto someone's sentence for associating with a group of people who have engaged in a number of actions deemed "criminal," such as selling drugs and assault. Predictably, this tough-on-crime approach criminalizes people for their social relationships and life circumstances, which often stem from poverty and harsh social policies.

In addition to gang enhancement and three strikes laws, the Crime Bill made it much easier for the government to deport immigrants without green cards. Specifically, it contains provisions that take away immigrants' due process rights and allow them to be deported without a hearing if convicted of an aggravated felony. This provision was given more teeth in 1996, when Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act and Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, which together broadened the definition of "aggravated felony" and thus expanded the grounds for deportation. Together, these laws disproportionately hurt Black immigrants, who are three times more likely to be deported due to legal records.

The Crime Bill laid important political, financial, and cultural foundations for the prison industrial complex (PIC) as it functions today—entrenching police as arbiters of public safety, financially incentivizing local governments to enact laws criminalizing more people, and expanding the role of policing and prisons in 'addressing' social problems.

POLICING CAN'T BE REFORMED

The pattern of popular reform proposals in the wake of flashpoint instances of police violence is well-known and enduring: More diverse police forces and leadership, better training, more oversight, more community engagement with officers, so on and so forth. These reforms presume the legitimacy of the police as a conduit to public safety, pumping more resources into training, equipment, and payroll. These reforms feed, rather than minimize, the very root cause of police violence: Policing itself. For example, the Crime Bill's "COPS" Program has granted over $14 billion to local law enforcement agencies since 1994, subsidizing local police budgets nationwide. Of that $14 billion, more than $1 billion has been allocated to the expansion of policing and surveillance infrastructure in public schools.

Additionally, reforms that expand police resources lead to more militarized police. The 1033 Program, established in 1997, empowers the Department of Defense (DOD) to funnel unused military equipment to local police forces. Over $7 billion worth of DOD property has been transferred since the program began, with over 8,000 law enforcement agencies around the country enrolled. These numbers underline the size and influence of policing and draw stark contrast to the local funds allocated for community-led, non-police safety initiatives.

These large investments in policing have inevitably contributed to the continued and accelerated caging of our people. For example, in Florida, the total number of incarcerated people increased over 67 percent from approximately 58,000 in 1994 to over 104,000 in 2010. In Wisconsin, the total number of incarcerated people increased from just over 9,500 in 1994 to over 22,000 in 2019, an increase of over 134 percent. These data are staggering, though not unique. Since 1994, more people are being locked up for more things and for longer periods of time, despite there being no definitive proof that these investments in policing have actually made communities safer or reduced crime.

The reforms contained in the Crime Bill represent a template for many of the reforms that law enforcement have proposed since it passed. These reforms, like those passed in 1994, will continue to expand the PIC, while our communities fight for resources needed to create true safety.

SAFETY COMES FROM COMMUNITY, NOT COPS

The safest communities across the country are not the communities with the most police—they are the communities with the most resources. The resource deficit fueled by policies that invest in policing, incarceration, and surveillance instead of health-affirming infrastructure has forced communities to exhibit creativity and imagination to create safety for themselves. In Atlanta, for example, the Policing Alternatives and Diversion Initiative conducts regular outreach to community members experiencing issues connected to mental health, extreme poverty, and substance use, intervening in lieu of police involvement to drive down interactions between the police and the public. This February, Families for Justice as Healing and The National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls established the Community Love Fund, which distributes recurring, direct cash relief to five formerly incarcerated women in Roxbury, Massachusetts for one year. Andrea James breaks down why these networks, led by people directly impacted by incarceration, are so vital: "We are reimagining our communities and creating what different looks like by making investments led by formerly incarcerated women on behalf of the most vulnerable among us." These ongoing initiatives are examples of how we can build safety together more widely, if only we had the resources. Police budgets pull resources away from the infrastructures that we need, undermining attempts to reproduce these community safety initiatives at scale.

BREAKING THE CYCLE THROUGH A PEOPLE'S PROCESS

The federal legislative process lacks accountability, extracts power from Black and other communities of color, creates barriers to participation for the people directly impacted by the legislation, and siloes issues, leading to narrowly crafted solutions which fail to account for the way social phenomena intersect and compound. To overturn the harms of the Crime Bill, we must listen to those most impacted: People in jails and prisons and their family members, communities targeted by police, students who attend schools with school police, and communities impacted by divestments from the social safety net.

Beginning this September, PCSF will facilitate a national People's Process that will shift power to our communities, and collectively create the legislation we want to replace the '94 Crime Bill. Our goal is to establish new federal funding streams that invest in health-affirming infrastructure and resources that actually keep us safe, and to flip the traditional cycle of making legislation on its head. The People's Process will use focus groups, digital outreach, surveys, and people's movement assemblies (PMAs) to solicit the expertise of those most impacted by the '94 Crime Bill. It will rely on and strengthen existing grassroots organizations, networks, and other formations of community members fighting to curb criminalization and create safer communities. The conclusion of the People's Process will be collaborative legislative drafting process, in which participating communities will draft the bill that will replace the '94 Crime Bill with new investments in our communities. We know what we need to create safety for ourselves, beyond cops and cages. Together, we can create policy solutions that center dignity and wholeness instead of punishment and disposability.

—————

About the Authors: Kamau Butcher, Kira Shepherd, Erica Perry, and Marbre Stahly-Butts are current and former members of Black-led, abolitionist organizations, as well as national movement lawyer and community networks. As individuals, their work and analysis have shaped and been shaped by such spaces as Bronx Defenders Organizing Project, Law for Black Lives, Common Justice, Workers Dignity, Peoples Coalition for Safety and Freedom and many others. ♦

Other posts by this author

|

2023 may 31

|

2023 apr 5

|

2023 mar 19

|

2023 mar 5

|

2023 mar 5

|

2023 mar 5

|

More... |

Replies