Transcription

Thoughts from the Heart

By Joseph Smith

2012 November 23rd

The Long Journey Back Home - Part II

What would I do if someday I stood face to face with a similar dilemma, having to choose between my tribe and family and the yearnings of my heart?? My answer was hard nosed. For now, I had no taste for belonging to the Jewish world if it meant an abdication of my dream, which was to find a spirituality that could coexist with my freedom. If the religion of my birth could not accept or accommodate my searching, questioning, freedom-bound nature, then I would have to find spiritual sustenance elsewhere. Not being able to attend Hebrew school, I was forced to attend the school of my father's family faith - Catholic school!!! Slowly, silently, I felt the heat of a secret stage light shift in my direction. Soon, it would be my turn to make choices, to decide who I was and where I stood on life's stage. I now felt myself to be on my own more deeply than ever before. I was running from a highly conditional world that was guarded by a multitude of gates, rules, and laws. And if the principle of love lay at its core, it seemed so well hidden, even from its gatekeepers, that I began to wonder why anyone would bother to look. I stopped all efforts to remain in my religion of birth and threw myself in the great mystery search that stood far beyond the forms or even the theologies of either of my parents' religions. There was one God, one who was both personal and all-knowing, and willing, despite all of our man-made roadblocks, to gift us with the grace of loving acceptance. Something neither one of my parents' religions did - the Jewish side didn't accept me due to who my father was - and the color of my skin. The Catholic side didn't accept me because of who my mother was - a "Jew", thus so was I under Jewish law. How dare I, a "Jew", attend their schools and not practice or attend "Mass". The concept of grace, for example, the free gift of God's love, is one that runs through Jewish scriptures. Yet it first took looking at the scriptures from a Christian perspective, that of my father's and Christian friends, for me to see that grace, or chesed, even existed as a concept in Judaism. You would never find a sign in a synagogue saying "God loves you!" Jews think of such adages as being strictly Christian.

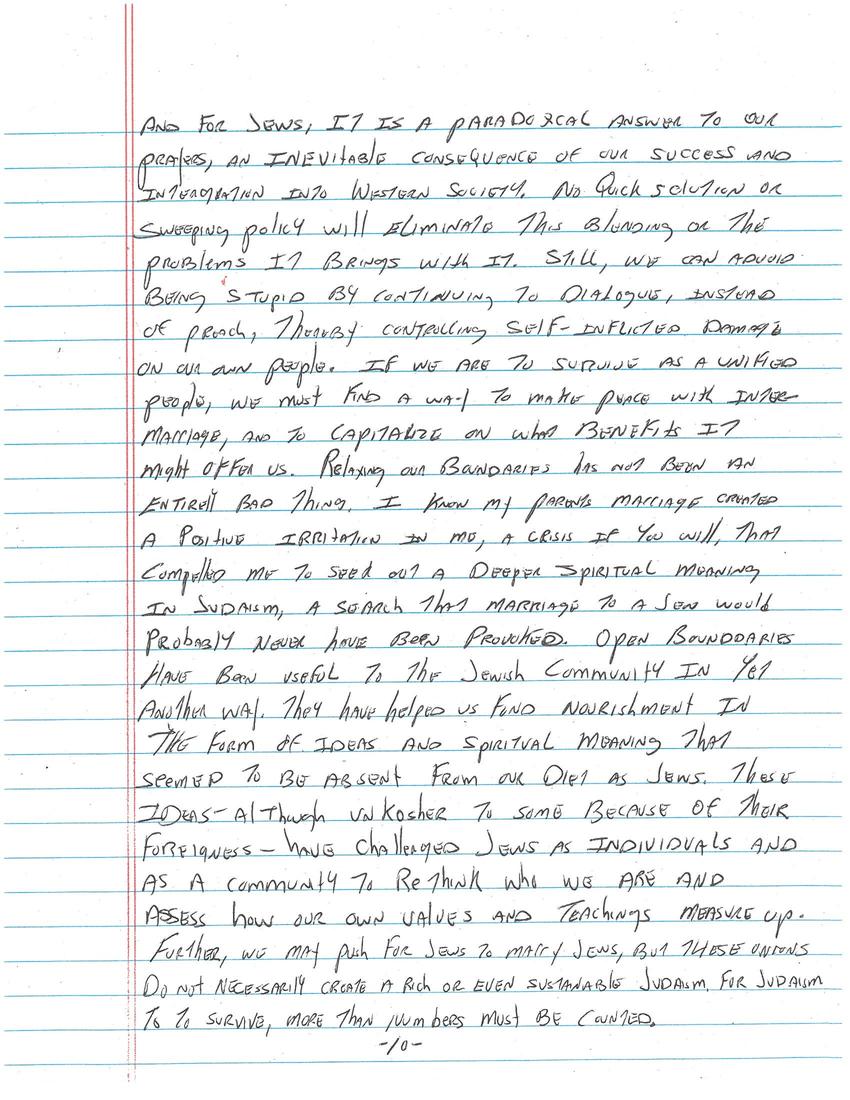

The idea that God's love follows us everywhere is a very Jewish one. I called my mother from England and told her that I had met someone, and we were discussing marriage and I wanted to know her thoughts and feelings about it. She chose her words very carefully, and just said why? You're not practicing Judaism, or are you?? No, I'm not. She just stated, follow your heart. I then discussed it with a few Jewish friends that were serving in my unit and the consensual belief was that intermarriage was a DREADED phenomenon because it presented the most serious danger to the Jewish people, dissolution. Jewish life, the thinking goes, will not survive if such pluralism is tolerated. I realized that the proponents of these views could not possibly know, as I did, how many Jewish young people were being turned away by this very mindset, which was so unappealing in its narrowness. I knew first hand that if the only way Jewish life could survive was to adopt such an isolationist sectarianism, many Jews would elect not to participate in the narrow parochial world at all. From the outside at the time, it is a strange problem that makes no logical sense. There is so much fear about Jewish people's dissolving that the rabbis are turning young people away in an effort to keep the Jewish ranks solid. I think that is because the place from which our policies arise is clearly not a rational one, but rather a highly charged emotional field. Sitting between two worlds of Jew and non-Jew, I can see that the issue of intermarriage has become like a lightning rod for the great distress that the Jewish community feels about its future. After centuries of pogroms, evacuations, and massacres, the Jewish people have just survived a near genocide, and the trauma is still in our system. Now, two generations after the Holocaust and living in a rapidly shifting society, the psyche of our people (just like that of an abused person) is still wounded and attempting to heal. So, like the rape victim who pulls in tightly in order to recover his or her violated boundaries, remaining contracted long after the attack, so the violated boundaries of our people are still taut in an effort to compensate and heal the brutal invasion into our lives. Sixty years later, the very topic of the Holocaust is, for some, enough to trigger anxiety and even hysteria. Intermarriage is a graphic example of relaxing our boundaries to the outside world, boundaries to date, are still healing. For this reason, some Jews automatically equate it with the evil that came when we last trusted the outside world enough to relax. But the truth is that intermarriage is here to stay. The blending of cultures and religions is an unprecedented communal phenomenon in America and elsewhere and for Jews, it is a paradoxical answer to our prayers, an inevitable consequence of our success and integration into Western society. No quick solution or sweeping policy will eliminate the blending or the problems it brings with it. Still, we can avoid being stupid by continuing to dialogue, instead of preach, thereby controlling self-inflicted damage on our own people. If we are to survive as a unified people, we must find a way to make peace with intermarriage, and to capitalize on what benefits it might offer us. Relaxing our boundaries has not been an entirely bad thing. I know my parents' marriage created a positive irritation in me, a crisis if you will, that compelled me to seek out a deeper spiritual meaning in Judaism, a search that marriage to a Jew would probably never have been provoked. Open boundaries have been useful to the Jewish community in yet another way. They have helped us find nourishment in the form of ideas and spiritual meaning that seemed to be absent from our diet as Jews. These ideas - although unkosher to some because of their foreignness - have challenged Jews as individuals and as a community to rethink who we are and assess how our own values and teachings measure up. Further, we may push for Jews to marry Jews, but these unions do not necessarily create a rich or even sustainable Judaism. For Judaism to survive, more than numbers must be counted.

Other posts by this author

|

2013 sep 3

|

2013 jul 1

|

2013 may 25

|

2013 may 22

|

2013 mar 20

|

2013 mar 20

|

More... |

Replies