Transcription

https://www.themarshallproject.org/2018/11/16/what-s-really-in-the-first-step-act

What’s Really in the First Step Act?

Too much? Too little? You be the judge.

Hailed by supporters as a pivotal moment in the movement to create a more fair justice system, endorsed by an unlikely alliance that includes President Donald Trump and the American Civil Liberties Union, the First Step Act is a bundle of compromises. As it makes its way through Congress it faces resistance from some Republicans who regard it as a menace to public safety and from some Democrats who view it as more cosmetic than consequential.

What would the bill actually do? The Marshall Project took a close look.

Reducing crack sentences The biggest immediate impact of the bill would be felt by nearly 2,600 federal prisoners convicted of crack offenses before 2010. That’s the year Congress, in the so-called Fair Sentencing Act, reduced the huge disparity in punishment between crack cocaine and the powdered form of the drug. The First Step Act would make the reform retroactive. Those eligible would still have to petition for release and go before a judge in a process that also involves input from prosecutors. With crack’s prevalence in many black neighborhoods in the 1980s, the crack penalty hit African Americans much harder than white powder cocaine users. That disparity has been a major example of the racial imbalance in the criminal justice system.

Curbing mandatory minimums The First Step Act would give federal judges discretion to skirt mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines for more people. Known as a “safety valve,” this exception now can only be used on nonviolent drug offenders with no prior criminal background. It would expand to include people with limited criminal histories. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that about 2,000 additional people each year would be eligible for exemption from mandatory sentences.

The bill also proposes to ease the severity of some automatic sentences. The mandatory minimum sentence doled out for serious violence or weighty drug charges would shrink by five years to 15 years. The federal “three strikes” rule, which prescribes a life sentence for three or more convictions that include serious violent felonies or drug trafficking, would instead trigger a 25-year sentence. Serious drug felonies that now result in automatic 20-year minimum sentences would be reduced to 15 years. An automatic trigger that adds 25 years if a defendant was convicted of two or more violent or trafficking charges while holding a gun would now apply only to people with prior records of similar offenses. The shortened mandatory sentences would not apply retroactively, which was a sticking point for some law enforcement groups endorsing the First Step Act. Those groups were crucial to winning Trump’s support.

Enforcing existing rules A number of reforms in the First Step Act just attempt to enforce what’s already written into law or policy. They include placing prisoners in facilities within 500 driving miles of their families or homes, requiring the Bureau of Prisons to match people with appropriate rehabilitative services, education and training opportunities and restating Congress’ intent to give prisoners up to 54 days off their sentences for good behavior; the current limit is 47 days. This “good time credit” fix would be retroactive, potentially freeing about 4,000 prisoners.

The bill gives inmates the opportunity to earn 10 days in halfway houses or in-home supervision for every 30 days they spend in rehabilitative programs. There is no limit on how many credits they can earn. Job training and education programs in prison would get $375 million in new federal funding. Churches and other outside groups would also get easier access to prisons to provide programming.

The Record The best criminal justice reporting from around the web organized by subject.

The First Step Act prohibits the shackling of pregnant prisoners, a practice that has been banned by Bureau of Prisons policy since 2008, and promises women free tampons and sanitary napkins.

The Bureau of Prisons is already supposed to be doing many of these things but has ignored Congressional mandates and its own policies, according to a number of federal audits and investigations. The First Step Act calls for greater use of halfway houses and home confinement, the least restrictive form of supervision, at a time when the federal prison system has been systematically dismantling its reentry programs. The proposed new law would also expand eligibility for compassionate release of elderly and terminally ill inmates, which would save the government housing and medical costs. Prison officials already have that authority but they release few who apply, denying thousands, some of whom die in custody.

Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this story included a section heading that incorrectly described a provision of the First Step Act. The bill would make retroactive a 2010 reduction in the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences.

Copied by CURE FOR 2310 WDC Cure@curenational.org

===

https://www.ncronline.org/news/justice/change-system-being-part-it

Change the system by being a part of it

Charlie and Pauline Sullivan, 45 years working for US prison reform

Sep 16, 2017

Charlie and Pauline Sullivan, both close to 80 and as agile as ever, believe in getting around. They estimate that since coming to Washington from Texas in 1985 they have covered over 1,000 miles through the halls of the U.S. capitol's six congressional office buildings — three in the Senate, three in the House. As co-founders of Citizens United for the Rehabilitation of Errants (CURE National), they go to every office, in every Congress, trying to make the case that legislation for humane criminal justice reforms is both a political and moral necessity.

Working in a nation that has the world's highest inmate population — 2.3 million people in 1,827 state and federal prisons, according to the Prison Policy Initiative — the Sullivans and their advocacy efforts might appear tiny up against the massiveness of the problems ranging from the brutality of long-term solitary confinements to incessant wrongful convictions.

"To change the system," Charlie Sullivan argues, "you must in some way become part of the system. Doing this, and keeping your principles, can be a difficult challenge. But from decades of experience, it can be done. In other words, as they say in Texas, "you have to be on the jury to hang the jury."

It was an experience in Texas in 1972 — seven days in a San Antonio jail on a nonviolent civil disobedience charge — that became a spark that flamed into a blaze to take action on behalf of mistreated prisoners, ex-prisoners and their families.

It was an unlikely calling for a boy born in 1940 into the comforts of a middle-class family in Mobile, Alabama, and whose father was a dentist and mother a homemaker. Charlie enrolled in a Catholic high school, only to leave before graduating to enter St. Mary's College in Kentucky and to be ordained a priest in 1965.

"I originally saw my future," he recalled on a recent afternoon in Washington, "as a Bing Crosby kind of parish priest — coaching sports for the parochial school kids taught by the nuns, dabbling in school musicals and never offering challenging sermons."

But this was the 1960s, with the church roiled by the liberalizing calls of Vatican II and the country dealing with racism in the South and a mindless war in Vietnam. With no taste for being bystander amid the turmoil, Sullivan joined the civil rights and antiwar campaigns. Except for a few bishops like Raymond Hunthausen and Thomas Gumbleton, he saw little or no church leadership on these issues.

"My particular bishop was taking no stands against what I saw as social sins all around us. I was at odds with a failing church leadership and, as a matter of conscience, I resigned the priesthood in 1969." He was one of many during that time.

Within a year, he met Pauline Fox who was a former member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet. They bonded and took to the road in a Volkswagen van that eventually carried them to San Antonio where, after Charlie's jail time, they founded CURE in 1972. It was the same year that singer Johnny Cash was in the White House to enlist Richard Nixon in the cause of restorative justice — a fruitless effort, it turned out.

During the Sullivan's Texas years, the state had some 25 prisons — all of which they visited, including Huntsville, which lead the nation in death row executions. Thirteen years later in 1985, the couple went national and brought the program to Washington with the same statement of purpose. The CURE mission:

We believe that prisons should be used only for those who absolutely must be incarcerated and that those who are incarcerated should have all the resources they need to turn their lives around. We also believe that human rights documents provide a sound basis for ensuring that criminal justice systems meet these goals. CURE is a membership organization. We work hard to provide our members with the information and tools necessary to help them understand the criminal justice system and advocate for change.

The Sullivans work out of a small rent-free office in the belfry of St. Aloysius Church blocks from the capitol. Unlike the ACLU's National Prison Project and the Innocence Project that are well-staffed by lawyers and amply funded, CURE pushes on with an annual budget of $50,000. Its strength is in its 30 chapters throughout the country

It has 15,000 members on its mailing list for a monthly, must-read newsletter.

In the past year, the couple has been able to persuade a few members of Congress to sponsor the Juvenile Justice Reform Act, the Second Chance Reauthorization Act, the Medicaid Coverage for Addiction Recovery and Expansion Act and others. Sponsorship hardly assures passage to a presidential bill signing, which means the Sullivan's cause-driven work goes on.

"I read and answer most of the letters from prisoners." Pauline Sullivan says. "So many of them ask for help with their legal issues and report dire conditions about their imprisonment. My greatest frustration is that I can't provide the help they request."

For Charlie, "My greatest joy over the years is working with so many wonderful people, some of whom have been with CURE from the beginning 45 years ago. Matthew 25 has been interpreted that 'I was in prison and you visited me.' But visiting is only one side of the coin. The other is advocacy, especially for the person to be released. In fact, the Catholic Worker movement interprets Matthew 25 as 'I was in prison and you liberated me.'

"The frustrations of the work include continuing year after year pushing for the release of prisoners who have rehabilitated themselves. That feeling is waived when, on occasion, the prisoner is finally waived."

The Sullivans' singular and heroic mission brings to mind the thought of George Bernard Shaw from the dedication of Man and Superman: "This is the true joy in life, the being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one; the being thoroughly worn out before you are thrown on the scrap heap; …"

[Colman McCarthy Colman directs the Center for Teaching Peace, a Washington non-profit. He began writing for NCR in 1966, and his most recent book is Baseball Forever.]

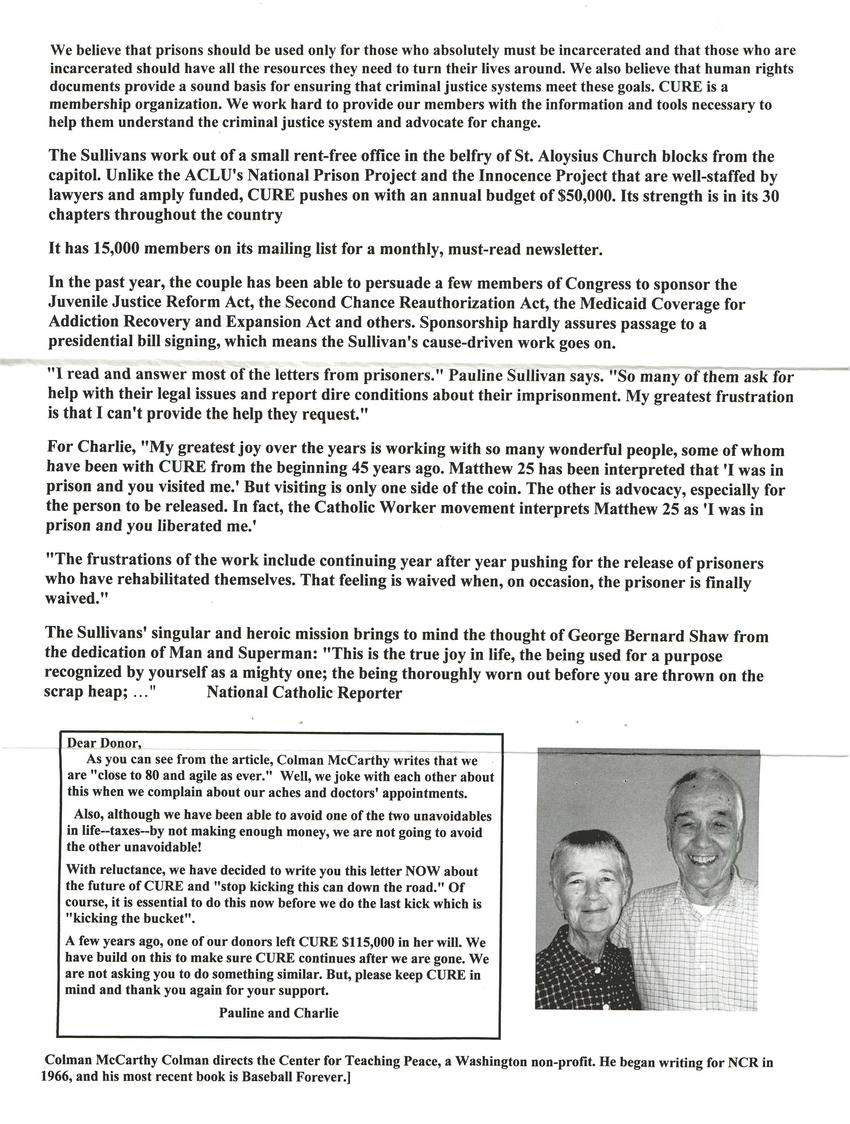

Dear Donor,

As you can see from the article, Colman McCarthy writes that we are "close to 80 and agile as ever." Well, we joke with each other about this when we complain about our aches and doctors' appointments.

Also, although we have been able to avoid one of the two unavoidables in life—taxes—by not making enough money, we are not going to avoid the other unavoidable!

With reluctance, we have decided to write you this letter NOW about the future of CURE and "stop kicking the can down the road." Of course, it is essential to do this now before we do the last kick which is "kicking the bucket."

A few years ago, one of our donors left CURE $115,000 in her will. We have build on this to make sure CURE continues after we are gone. We are not asking you to do something similar. But please keep CURE in mind, and thank you again for your support.

Pauline and Charlie

===

https://apw.dhinitiative.org/collection-description

American Prison Writing Archive

Collection Description

History, Process, Mission

The American Prison Writing Archive evolved from a book project completed in 2014 with the publication of Fourth City: Essays from the Prison in America, the largest collection to date of non-fiction writing by currently incarcerated Americans writing about their experience inside. The submission deadline for Fourth City passed in August 2012, yet submissions never ceased. The imperative to build the APWA grew from the clear evidence that, once invited, incarcerated people would not give up the chance to tell their stories. The APWA currently hosts over 1,600 essays, enough work to fill over twenty-two volumes the size of Fourth City (a 338-page, 7”x10” text).

Essays are solicited through prisoner-support newsletters and a call for essays in Prison Legal News. Writers then write to request our permissions-questionnaire (PQ). The PQ is then returned with essays on anything that falls within the wide field described in the PQ. All submissions are read and, with very rare exceptions, scanned, and ingested. The information gathered from the PQ enables faceted searching. All handwritten essays are also transcribed—and can be transcribed by any visitor—to make them fully searchable. Anyone with first-hand experience inside US carceral institutions today is eligible to submit essays. This includes prison employees and volunteers, who materially shape the day-to-day conditions in which incarcerated people live, and who are in turn deeply affected by their work. A truly inclusive vision of life inside requires the testimony of everyone who lives, works, or volunteers in prisons today. In this light, readers will note the under-representation of women, trans, and gender nonconforming people in the archive. We invite all APWA visitors who work with or know incarcerated people to help us in increasing contributions from these populations, as well as from prison workers and volunteers.

Amid the unprecedented American experiment in mass-scale incarceration, the APWA hopes to disaggregate this mass into the individual minds, hearts and voices of incarcerated writers. At the same time, like other witness literatures, writers from across the nation yield insights into the common traits of their experience. Visitors can search by state, author attributes, etc. (See and explore this page’s left sidebar.) They can also search by keywords, and, after a keyword search, use the right sidebar for more specific author attributes. With these tools, visitors can not only read widely; they can curate their own virtual collections.

The mission of the APWA is to replace speculation on and misrepresentation of prisons, imprisoned people, and prison workers with first-person witness by those who live and work on the receiving end of American criminal justice. No single essay can tell us all that we need to know. But a mass-scale, national archive can begin to strip away widely circulated myths and replace them with some sense of the true human costs of the current legal order. By soliciting, preserving, digitizing and disseminating the work of imprisoned people, prison workers and volunteers, we hope to ground national debate on mass incarceration in the lived experience of those who know prisons best.

Principal Investigator

Doran Larson, Ph.D.

Walcott-Bartlett Professor of Literature and Creative Writing

dlarson@hamilton.edu

Other posts by this author

|

2023 may 31

|

2023 mar 20

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

More... |

Replies