Transcription

JUSTICE AND EQUALITY CREATE A "CLASS DISTINCTION" THAT HAS MANY FLAWS IN MASSACHUSETTS.

BY: LUIS D. PEREZ

September 1st, 2012

TO: MEMBERS OF THE MEDIA

PRESS RELEASE

FR: Luis D. Perez W33937

NCCI-GARDNER - P.O. Box 466

Gardner, Mass. 01440

http://betweenthebars.org/blogs/350/luis-d-perez

Dear Members of the community;

Recently I have some media exposure in connection to my legal efforts; In correcting a Constitutional error in Massachusetts Court. But the entire truth is twisted and misleading and this is the only avenue available to me at this time.

I already filed a Habeas Corpus - Woburn Superior Court and we will have the opportunity to address those issues. You can look at the case Docket Number MICV2012-02811-J.

Massachusetts for many years has passed laws on top of laws and when we challenge the constitutionality of those laws, the courts go around adopting new rulings that suit them in application and dishing out justice for all.

Let me further explain some of the issues in question. The Massachusetts murder statutes on criminal procedures were NULL AND VOID as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court Ruling on the death penalty Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238-July/1972.

The Massachusetts statutes on murder G.L. c. 265 1 did not have the punishment requirements of G.L. c. 265 2, it was NULLIFIED by the U.S. Supreme Court Ruling. - At that time Massachusetts murder statutes did not have saving clause or severability clause between the statutes. After July 30, 1972, Massachusetts Judges were without any new authorization to sentence individuals convicted of murder to life in prison.

Back on July-1972, other States have a moratorium until the Legislation gives proper authorization to sentence individuals on capital murder. Without any question, Massachusetts Judges were indeed Legislating from the bench. - It was not until 1979 that the Legislature gave the authorization and it was not until 1982 when the Legislation further provide a saving clause, correct the statutes and removed the death penalty from the murder statutes. Please read the history on those changes for further understanding.

Therefore, from July 30, 1972 to 1979 the state court was sentencing individuals to life in prison without authorization from the Legislative Branch. I was convicted on that time period, using those murder statutes on January 23, 1973 and my co-defendant pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and received six-year term of probation despite the mandate of G.L. c. 265, 2, that second degree murder be punished by imprisonment for life. Please read the official papers from the court.

Massachusetts Judges never gave a direct answer to the central question on this entire matter. Since there is NO SAVING CLAUSE on the statutes, they become NULLIFIED when you are adopting a new ruling. The courts responded on some other issues without giving a direct answer to the question of NO SAVING CLAUSE. NOTE: (A saving Clause is a simple constitutional notification indicating that in case of a new ruling the law will stand until the Legislation makes the adjustment.) If the judges were legally correct between 1972-1979 why then would you have to make corrections in the statutes (7) years later?

While on the other hand, President Bush won the election in Florida on the same issue Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98, 115 (2000) "No Court in this country can enlarge its authority or legislate from the bench". However, here in Massachusetts Courts have done this as normal proceedings, instead of CORRECTING A CONSTITUTIONAL ERROR.

Now we have a new ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court rejecting the sentencing of juveniles to life without parole. Already in other states like Iowa the Governor reduced a juvenile life sentence to a 60 years term. In my case, I have to bring the issue to Court to determine if I was a juvenile back in 1971-1972 since people under 21 years old was considered a minor in Massachusetts.

I sincerely hope that I will be able to address these issues in court and that somehow a constitutional lawyer can take the case to correct a constitutional error, and apply the Equal Protection Clause of the XIV-Amendment of the Constitution to my case.

Respectfully yours and in the struggle for freedom.

LUIS D. PEREZ

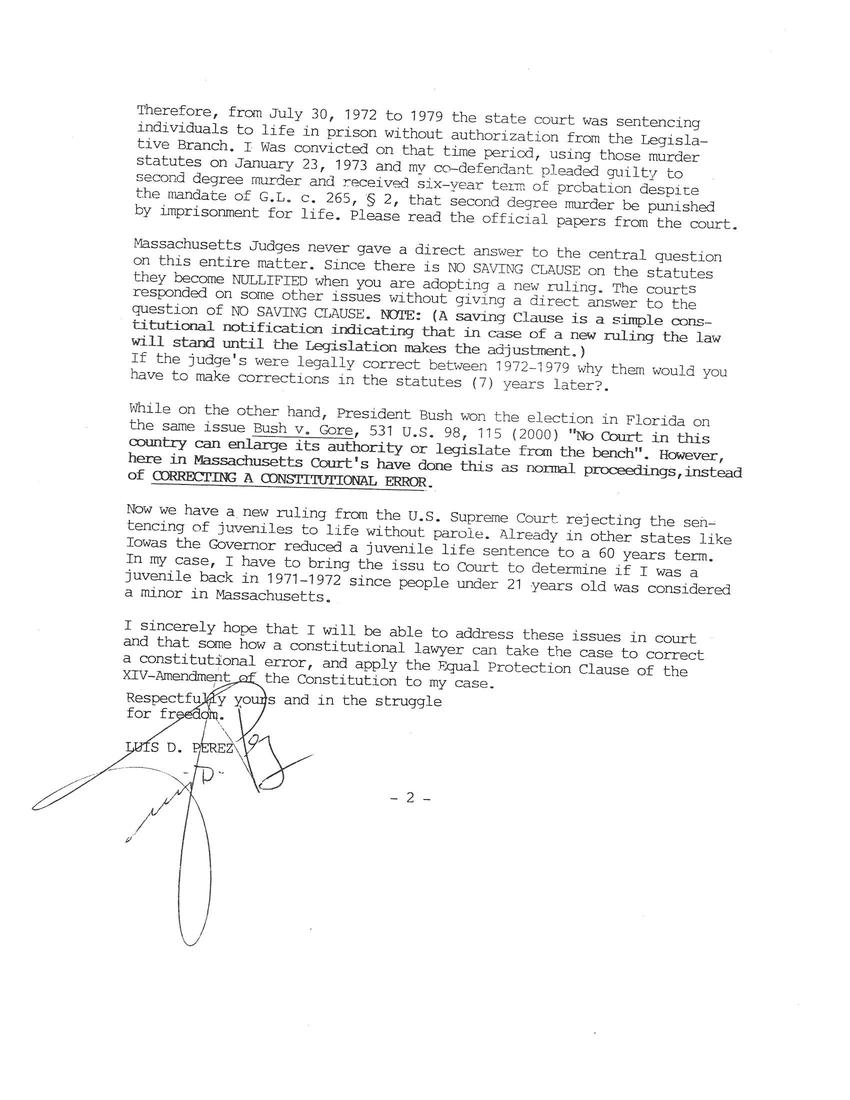

Inmate: Ruling makes life term in 1971 Lowell murder illegal

By Lisa Redmond

lredmond@lowellsun.com

GARDNER - An NCCI-Gardner inmate who is serving a life sentence for murder and has a history of headline-grabbing actions is asking to be brought before a state judge to argue his civil rights are being violated with an illegal sentence.

Luis Perez says he was 19 and a minor when he began serving a life sentence for the 1971 murder of a Lowell man over what turned out to be $1,000 in fake bills.

Perez, who is representing himself, wrote in documents not yet filed in Middlesex Superior Court that he is being held illegally in state prison.

Perez is relying on a June decision by the country's highest court to bolster his cause. In a 5-4 vote, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down mandatory-sentencing laws of life without parole for "juveniles" under 18 under the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.

While Perez was 19 at the time of his sentencing in 1973, he argues in documents provided to The Sun that he was a minor - someone under 21 - and the new federal law should be applied to his case.

A U.S. District Court "report and recommendation" notes that the state Parole Board and the governor have denied Perez a parole hearing and that he has filed a handful of motions for new trials. All have either been waived or denied.

Perez has been in the headlines before.

In 2002, he wrote a book from prison, Despartriado: Man Without Country. In 1993, Perez, while attempting to run for governor from behind prison walls, went on a hunger strike to stop his transfer to another prison. And as recently as March, he issued a "press release" about prison overcrowding.

Under Massachusetts law, anyone 14 and older charged with first-degree murder is tried as an adult and, if convicted, automatically sentenced to life without parole.

Perez was convicted of first-degree murder, armed robbery, arson and larceny under the joint-venture theory with Luis Alvarez, who pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in the fatal shooting of Peter Kyriazopoulos, also known as Peter Poulos, on April 22, 1971, in his Lowell apartment.

According to court documents:

Kyriazopoulos was entertaining Judy Varoski, Maureen Donahue and a man identified as "George" in his Lowell apartment on April 21, 1971. Varoski testified at trial that George showed Varoski five $1,000 bills belonging to Kyriazopoulos.

The next day, Varoski told Luis Alvarez about the money, knowing that his friend, Perez, needed money. Alvarez mentioned to Perez that Varoski knew someone who had money. A plan was hatched to steal the money from the victim's apartment.

Bringing a rifle with him, Perez and Alvarez went into Kyriazopoulos' apartment, shot him three times in the head and stole his money. Upon reaching the car, Alvarez threw a bank book containing $1,000 at Tony Mangula and told him that the money was "fake" and that Perez had shot Kyriazopoulos.

Perez stopped at a bridge and threw the rifle into a river, the documents then say. Alvarez and Perez drove the white car used to drive to Kyriazopoulos' apartment to another area and Perez set the car on fire.

Follow Lisa Redmond on Twitter @lredmond13.

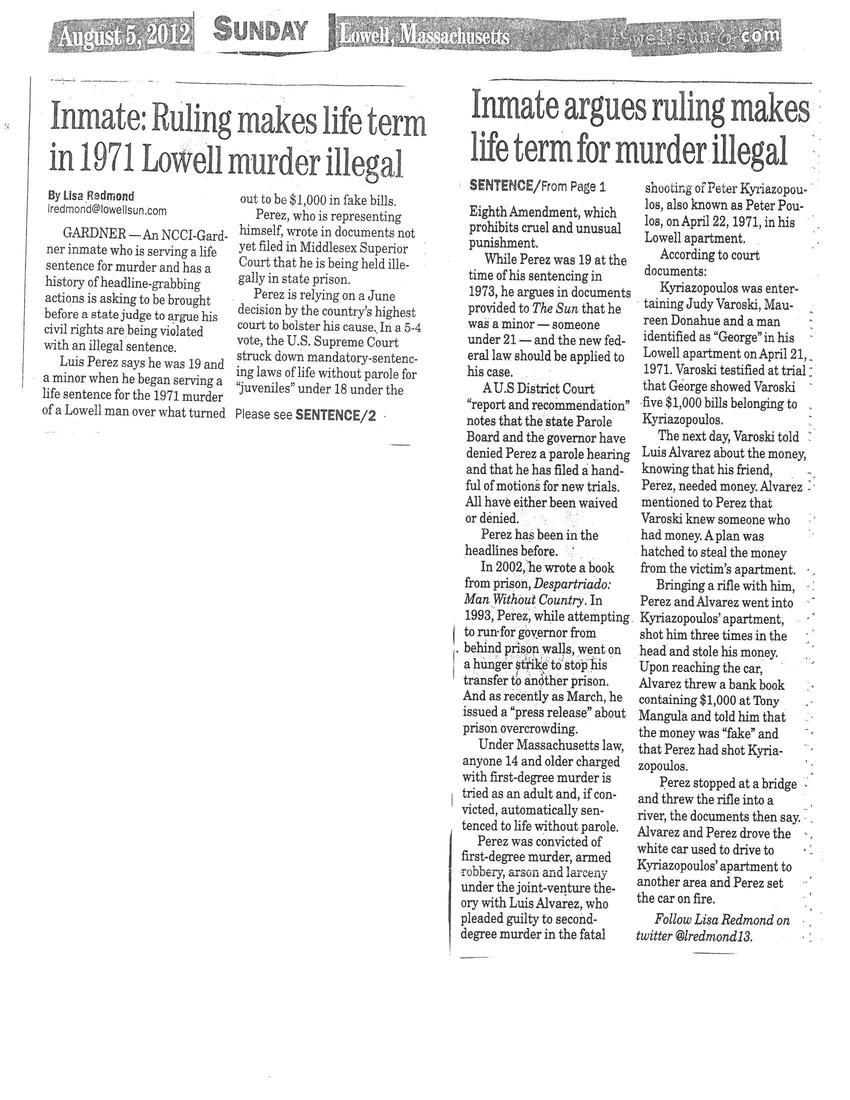

(7 years to correct the status?) At that time many prisoners was sentenced to life?

History -

BL 94, 4-6; CL 14, 4, 5; 1697, 17, 1784, 44, 1; 1804, 123, 1; 1836, 125, 1; 1858, 154, 4, 5; 1860, 160, 4, 5; 1882, 202, 4, 5; 1902, 207, 2; 1951, 203; 1955, 770, 78; 1956, 731, 12; 1979, 488, 2; 1982, 554, 3.

Editorial Note -

The 1951 amendment rewrote the penalty for first degree murder, and forbade the parole of a person convicted of first degree murder.

The 1955 amendment rewrote the last sentence of this section.

The 1956 amendment inserted the last sentence in place of the former last sentence.

The 1979 amendment deleted the first two sentences of this section and inserted in their place a sentence authorizing capital punishment for those guilty of murder. Section 1 provides:

SECTION 1. It is hereby declared that the value of capital punishment as a deterrent for crime is a complex factual issue the resolution of which properly rests with the general court, which has evaluated the results of statistical studies in the terms of the local conditions with a flexibility of approach not available to the courts, and that the general court has so found and defined those crimes and those criminals for which capital punishment is most probably an effective deterrent. It is hereby further declared that the value of capital punishment as retribution, although unappealing to many, is an expression of society's moral outrage at the commission of particularly heinous crimes and that capital punishment for the crime of murder cannot be viewed as invariably disproportionate to the severity of that crime. It is hereby further declared that in the past nine years the Congress and over thirty-five states have enacted new death penalty statutes by legislative measures adopted by the people's chosen representatives. It is hereby further declared that the ability of the people of the commonwealth to express their preference through their duly elected representatives must not be shut off by the intervention of the judicial department on the basis of a constitutional test intertwined with an assessment of contemporary standards and that the judgment of the general court weighs heavily in ascertaining such standards in this commonwealth. It is hereby further declared that in a democratic society, legislatures, and here, in this commonwealth, the general court is the body constituted to respond to the will of the people. It is hereby further declared that the declarations set forth above include and reflect the declarations already made by the highest court of the land which express that this subject of whether there be or not be capital punishment in any state is peculiarly questions of legislative, not judicial decision, and, in this commonwealth, that question is one for the general court to decide. It is hereby further declared that the following proposed legislation is the result of long study and review of the work and experience of other jurisdictions which have satisfied all those norms demanded by the Supreme Court of the United States to safeguard against all of the elements of arbitrariness and capriciousness condemned by said court in former state death penalty statutes.

The 1982 amendment rewrote this section, changing the penalty for a first-degree murder conviction from death to life imprisonment, and providing for the death penalty for those found guilty of murder committed with deliberately premeditated malice aforethought or with extreme atrocity or cruelty.

O'CONNOR, Justice (dissenting).

The defendant's convictions depended on the jury's believing Alvarez, and the jury could not have believed both Alvarez and the defendant. Therefore, a comparison of their credibility was critical. The judge's instructions must be evaluated in that context. I believe that the effect of the jury charge "was to throw the weight of the judge's opinion [as to the relative credibility of Alvarez and the defendant] in the scales against the defendant", Commonwealth v. Foran, 110 Mass. 179, 180 (1872), and that this was error which created a substantial likelihood of a miscarriage of justice, requiring a new trial.

After summarizing the defendant's testimony, the judge instructed the jury that in weighing his testimony they were entitled to consider his interest in the outcome of the case. Then, after summarizing Alvarez's testimony, the judge charged the jury that in weighing his testimony the jury could consider the fact that Alvarez inculpated himself as well as the defendant, that Alvarez told the court that he was aware that he was inculpating himself, and that when this was done Alvarez had counsel. The clear import of these instructions was that the defendant's testimony was self-serving, and therefore entitled to little weight, but that Alvarez's testimony was not self-serving but rather was against his own interest, and therefore was worthy of belief.

The instruction was erroneous for two reasons. First, determination of the credibility of witnesses is within the exclusive province of the jury, and must not be encumbered by the possible influence of the judge's opinion. Commonwealth v. Sneed, 376 Mass. 867, 870, 872, 383 N.E.2d 843 (1978). Commonwealth v. Barry, 9 Allen 276, 278-279 (1864). See G.L. c. 231, 81. Second, the implication that Alvarez's testimony was against his interest was misleading because it suggested, without evidentiary support, and perhaps contrary to fact, that he had nothing to gain by it. See Commonwealth v. Barry, supra at 277, 278. Alvarez had been indicted for murder in the first degree, armed robbery, arson, and larceny of a motor vehicle in connection with the events to which he testified. At the time of the defendant's trial, those indictments were still pending. Disposition of Alvarez's case had been continued repeatedly during the months prior to the defendant's trial. Alvarez may well have believed that his own conviction was likely and that assisting the Commonwealth would bring its reward. If Alvarez did gamble on earning the Commonwealth's favor, it would appear that he won. A week after the defendant was convicted, Alvarez appeared before the judge who presided over the defendant's trial and pleaded guilty to murder in the second degree, armed robbery, arson, and larceny of a motor vehicle. The judge sentenced Alvarez to concurrent sentences of seven to twenty years on the indictments for armed robbery and arson. Despite the mandate of G.L. c. 265, 2, that second degree murder be punished by imprisonment for life, the judge sentenced Alvarez to a six-year term of probation on the indictment for murder, the term to take effect at the expiration of the sentence imposed on the armed robbery indictment. The judge placed the indictment for larceny of a motor vehicle on file.

I agree with the court's statement that "we examine the charge in its entirety to determine its overall impact on the jury." Supra at 640. I do not agree, however, that statements in a jury charge indicating the judge's opinion of the credibility of particular witnesses, or direct or indirect misstatements of a witness's motivation in testifying, are corrected by general statements, no matter how many times repeated, that the jurors are the sole judges of the facts and that it is for them to decide what weight will be given to the evidence. This is the holding of Commonwealth v. Foran, supra at 180. We cannot fairly assume that as a result of being told that it is for them to decide what witnesses are to be believed, jurors can be relied on to ignore the judge's proffered opinion as to the facts.

In my opinion, the jury instructions were erroneous because they were misleading as to a matter that was relevant to Alvarez's credibility and because the exclusive province of the jury to find facts was invaded by the judge. Because Alvarez's credibility was critical to the convictions, I believe that there is a substantial likelihood that a miscarriage of justice has occurred. G.L. c. 278, 3SE. Accordingly, I would reverse the convictions and order a new trial.

Other posts by this author

|

2023 feb 2

|

2022 dec 26

|

2022 nov 5

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 jun 23

|

2022 may 4

|

More... |

Replies