Transcription

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/04/19/copays/

The steep cost of medical co-pays in prison puts health at risk

When we consider the relative cost of medical co-pays to incarcerated people who typically earn 14 to 62 cents per hour, it's clear they can be cost-prohibitive. Co-pays that take a large portion of your paycheck make seeking medical attention a costly choice.

by Wendy Sawyer, April 19, 2017

If your doctor charged a $500 co-pay for every visit, how bad would your health have to get before you made an appointment? You would be right to think such a high cost exploitative, and your neighbors would be right to fear that it would discourage you from getting the care you need for preventable problems. That’s not just a hypothetical story; it’s the hidden reality of prison life, adjusted for the wage differential between incarcerated people and people on the outside.

In most states, people incarcerated in prisons and jails pay medical co-pays for physician visits, medications, dental treatment, and other health services. These fees are meant to partially reimburse the states and counties for the high cost of medical care for the populations they serve, which are among the most at-risk for both chronic and infectious diseases. Fees are also meant to deter people from unnecessary doctor’s visits. Unfortunately, high fees may be doing more harm than good: deterring sick people from getting the care they really do need.

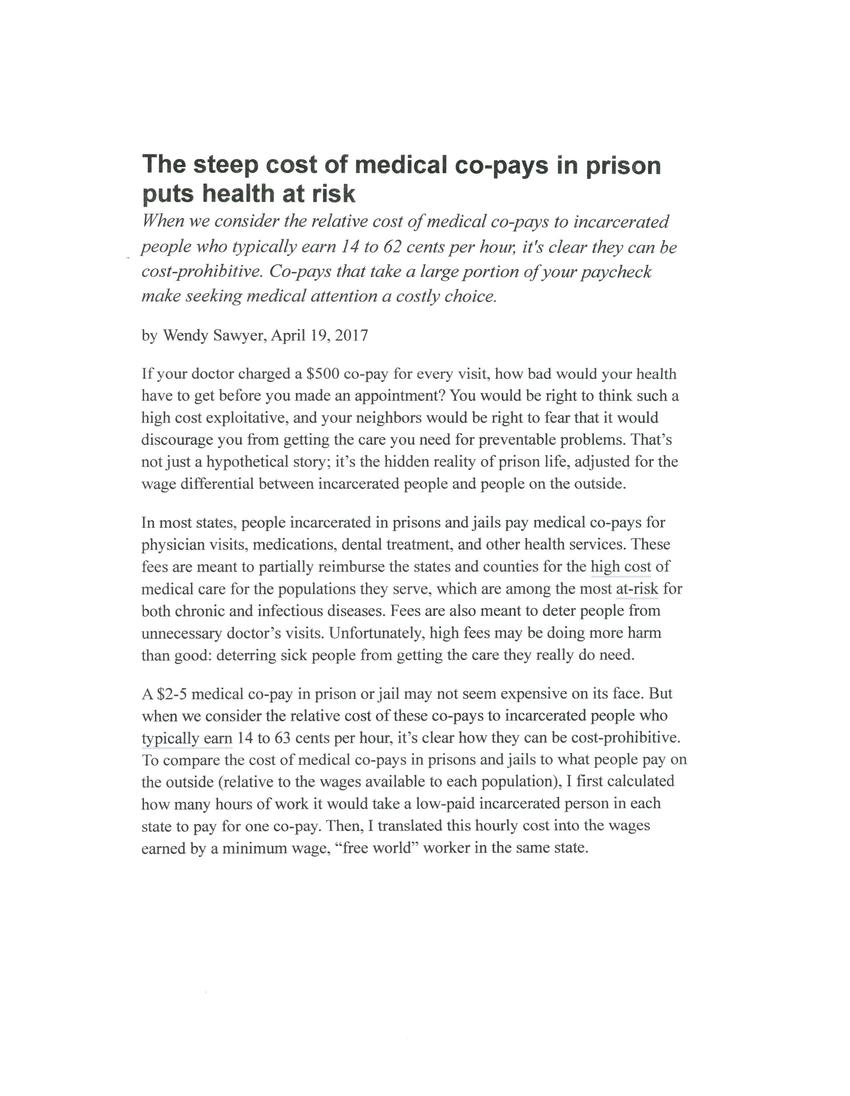

A $2-5 medical co-pay in prison or jail may not seem expensive on its face. But when we consider the relative cost of these co-pays to incarcerated people who typically earn 14 to 63 cents per hour, it’s clear how they can be cost-prohibitive. To compare the cost of medical co-pays in prisons and jails to what people pay on the outside (relative to the wages available to each population), I first calculated how many hours of work it would take a low-paid incarcerated person in each state to pay for one co-pay. Then, I translated this hourly cost into the wages earned by a minimum wage, “free world” worker in the same state.

See the table below for co-pay fees and minimum wages in each state. Policy details and sourcing information can be found in the Appendix. For another perspective, I also graphed what percent of the lowest-paid incarcerated person’s monthly earnings is taken by a single co-pay in each state.

In West Virginia, a single visit to the doctor would cost almost an entire month’s pay for an incarcerated person who makes $6 per month. For someone earning the state minimum wage, an equivalent co-pay that takes the same 125 hours to earn would cost an unconscionable $1,093. In Michigan, it would take over a week to earn enough for a single $5 co-pay, making it the free world equivalent of over $300. I found that fourteen states

charge a medical co-pay that is equivalent to charging minimum wage workers more than $200.

The excessive burden of medical fees and co-pays is most obvious in states where many or all incarcerated people are paid nothing for their work: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. Texas

is the most extreme example, with a flat $100 yearly health services fee, which some officials are actually trying to double to $200. People incarcerated in these states must rely on deposits into their personal accounts – typically from family – to pay medical fees. In most places, funds are automatically withdrawn from these accounts until the balance is paid, creating a debt that can follow them even after release.

Co-pays that take a large portion of prison wages make seeking medical attention a costly choice.

Co-pays in the hundreds of dollars would be unthinkable for non-incarcerated minimum wage earners. So why do states think it’s acceptable to charge people making pennies per hour such a large portion of their earnings? Some might argue that incarcerated people have nothing better to spend wages on than medical care. But wages allow incarcerated people to buy things they need that the prison does not provide: toiletries, over-the-counter medicine, additional clothes and shoes, as well as phone cards, stamps, and paper to help them maintain contact with loved ones. Co-pays that take a large portion of prison wages make seeking medical attention a costly choice.

Part of the justification for charging incarcerated people medical co-pays is to force them to make difficult choices. Administrators want to deter “frivolous” medical visits. The National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC), however, argues that abuses of sick call can be managed with “a good triage system,” without imposing fees that also deter necessary medical services. And although providers must treat people regardless of their ability to pay, incarcerated people with “low health literacy” may not understand this right. The NCCHC warns that co-pays may actually jeopardize the health of incarcerated populations, staff, and the public.

Out-of-reach co-pays in prisons and jails have two unintended but inevitable consequences which make them counterproductive and even dangerous. First, when sick people avoid the doctor, disease is more likely to spread to others in the facility – and into the community, when people are released before being treated. Second, illnesses are likely to worsen as long as people avoid the doctor, which means more aggressive (and expensive) treatment when they can no longer go without it. Correctional agencies may be willing to take that risk and hope that by the time people seek care, their treatment will be someone else’s problem. But medical co-pays encourage a dangerous waiting game for incarcerated people, correctional agencies, and the public – which none of us can afford.

For details and sourcing information on co-pays (and what happens when incarcerated patients can’t afford them), see the Appendix.

March 2020 update: Please see our post about legislative changes in California, Illinois, and Texas to see what has changed since we first published this briefing, and our page tracking correctional responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, which includes temporary suspensions of copays in some states.

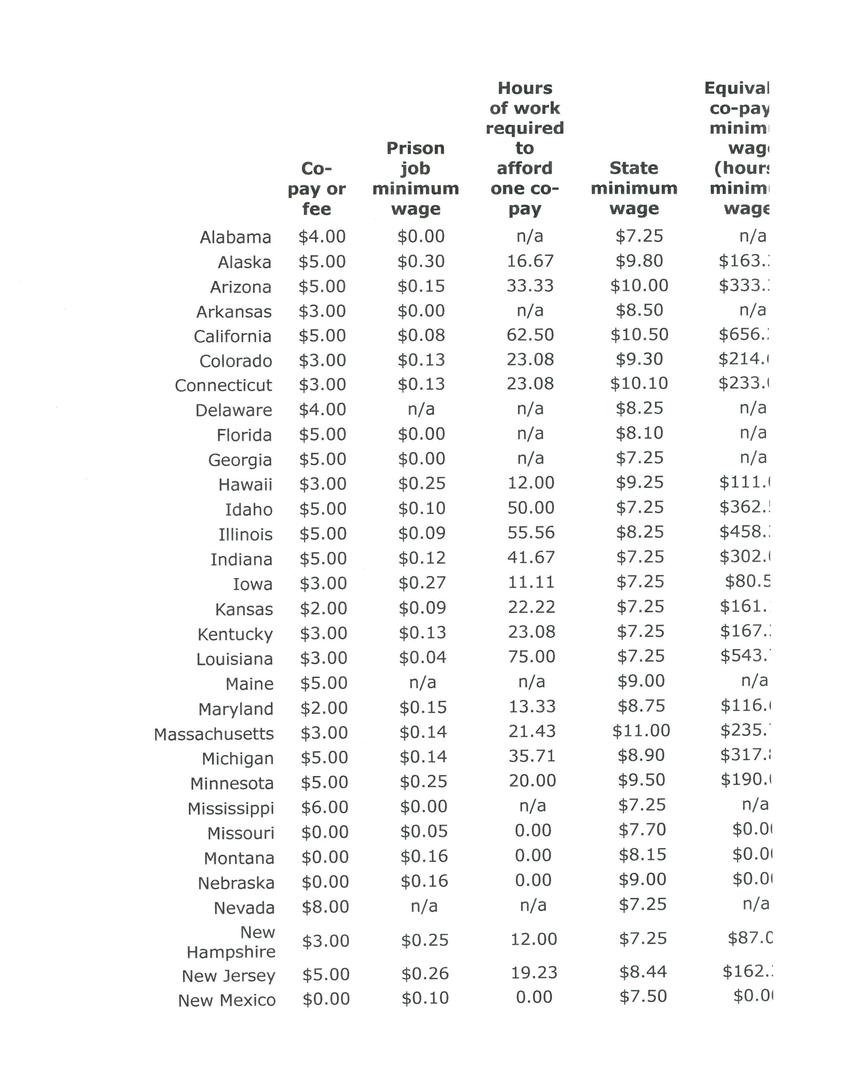

Co-pay or fee Prison job minimum wage Hours of work required to afford one co-pay State minimum wage Equivalent co-pay at minimum wage

(hours x minimum wage)

Alabama $4.00 $0.00 n/a $7.25 n/a

Alaska $5.00 $0.30 16.67 $9.80 $163.33

Arizona $5.00 $0.15 33.33 $10.00 $333.33

Arkansas $3.00 $0.00 n/a $8.50 n/a

California

$5.00 $0.08 62.50 $10.50 $656.25

Colorado $3.00 $0.13 23.08 $9.30 $214.62

Connecticut $3.00 $0.13 23.08 $10.10 $233.08

Delaware $4.00 n/a n/a $8.25 n/a

Florida $5.00 $0.00 n/a $8.10 n/a

Georgia $5.00 $0.00 n/a $7.25 n/a

Hawaii $3.00 $0.25 12.00 $9.25 $111.00

Idaho $5.00 $0.10 50.00 $7.25 $362.50

Illinois

$5.00 $0.09 55.56 $8.25 $458.33

Indiana $5.00 $0.12 41.67 $7.25 $302.08

Iowa $3.00 $0.27 11.11 $7.25 $80.56

Kansas $2.00 $0.09 22.22 $7.25 $161.11

Kentucky $3.00 $0.13 23.08 $7.25 $167.31

Louisiana $3.00 $0.04 75.00 $7.25 $543.75

Maine $5.00 n/a n/a $9.00 n/a

Maryland $2.00 $0.15 13.33 $8.75 $116.67

Massachusetts $3.00 $0.14 21.43 $11.00 $235.71

Michigan $5.00 $0.14 35.71 $8.90 $317.86

Minnesota $5.00 $0.25 20.00 $9.50 $190.00

Mississippi $6.00 $0.00 n/a $7.25 n/a

Missouri $0.00 $0.05 0.00 $7.70 $0.00

Montana $0.00 $0.16 0.00 $8.15 $0.00

Nebraska $0.00 $0.16 0.00 $9.00 $0.00

Nevada $8.00 n/a n/a $7.25 n/a

New Hampshire $3.00 $0.25 12.00 $7.25 $87.00

New Jersey $5.00 $0.26 19.23 $8.44 $162.31

New Mexico $0.00 $0.10 0.00 $7.50 $0.00

New York $0.00 $0.10 0.00 $9.70 $0.00

North Carolina $5.00 $0.05 100.00 $7.25 $725.00

North Dakota $3.00 $0.19 15.79 $7.25 $114.47

Ohio $2.00 $0.10 20.00 $8.15 $163.00

Oklahoma* $4.00 $0.05 80.00 $7.25 $580.00

Oregon $0.00 $0.05 0.00 $9.75 $0.00

Pennsylvania $5.00 $0.19 26.32 $7.25 $190.79

Rhode Island $3.00 $0.29 10.34 $9.60 $99.31

South Carolina $5.00 $0.00 n/a $7.25 n/a

South Dakota $2.00 $0.25 8.00 $8.65 $69.20

Tennessee $3.00 $0.17 17.65 $7.25 $127.94

Texas

$100.00 per year $0.00 n/a $7.25 n/a

Utah $5.00 $0.40 12.50 $7.25 $90.63

Vermont $0.00 $0.25 0.00 $10.00 $0.00

Virginia $5.00 $0.27 18.52 $7.25 $134.26

Washington $4.00 n/a n/a $11.00 n/a

West Virginia $5.00 $0.04 125.00 $8.75 $1,093.75

Wisconsin $7.50 $0.09 83.33 $7.25 $604.17

Wyoming $0.00 $0.35 0.00 $7.25 $0.00

Federal $2.00 $0.12 16.67 $7.25 $120.83

Average* $3.47 $0.14 25.09 $8.30 $208.25

Stay Informed

Get the latest updates:

Prison Policy Initiative newsletter (?)

And our other newsletters:

Research Library updates (?)

Prison gerrymandering campaign (?)

Email:

Name (optional):

State (optional):

Work with us

We are hiring a Senior Editor and a Senior Engineer. Apply today.

Support us

Can you make a tax-deductible gift to support our work?

Donate

Home Page > Briefings > The steep cost of medical co-pays in prison puts health at risk

The steep cost of medical co-pays in prison puts health at risk

When we consider the relative cost of medical co-pays to incarcerated people who typically earn 14 to 62 cents per hour, it's clear they can be cost-prohibitive. Co-pays that take a large portion of your paycheck make seeking medical attention a costly choice.

by Wendy Sawyer, April 19, 2017

If your doctor charged a $500 co-pay for every visit, how bad would your health have to get before you made an appointment? You would be right to think such a high cost exploitative, and your neighbors would be right to fear that it would discourage you from getting the care you need for preventable problems. That’s not just a hypothetical story; it’s the hidden reality of prison life, adjusted for the wage differential between incarcerated people and people on the outside.

In most states, people incarcerated in prisons and jails pay medical co-pays for physician visits, medications, dental treatment, and other health services. These fees are meant to partially reimburse the states and counties for the high cost of medical care for the populations they serve, which are among the most at-risk for both chronic and infectious diseases. Fees are also meant to deter people from unnecessary doctor’s visits. Unfortunately, high fees may be doing more harm than good: deterring sick people from getting the care they really do need.

A $2-5 medical co-pay in prison or jail may not seem expensive on its face. But when we consider the relative cost of these co-pays to incarcerated people who typically earn 14 to 63 cents per hour, it’s clear how they can be cost-prohibitive. To compare the cost of medical co-pays in prisons and jails to what people pay on the outside (relative to the wages available to each population), I first calculated how many hours of work it would take a low-paid incarcerated person in each state to pay for one co-pay. Then, I translated this hourly cost into the wages earned by a minimum wage, “free world” worker in the same state.

Graph showing how much minimum wage earners in each state would pay if a single co-pay took as many hours to earn as a co-pay charged to an incarcerated person does. The average equivalent co-pay is about $200 and in West Virginia, it's over $1,000. See the table below for co-pay fees and minimum wages in each state. Policy details and sourcing information can be found in the Appendix. For another perspective, I also graphed what percent of the lowest-paid incarcerated person’s monthly earnings is taken by a single co-pay in each state.

In West Virginia, a single visit to the doctor would cost almost an entire month’s pay for an incarcerated person who makes $6 per month. For someone earning the state minimum wage, an equivalent co-pay that takes the same 125 hours to earn would cost an unconscionable $1,093. In Michigan, it would take over a week to earn enough for a single $5 co-pay, making it the free world equivalent of over $300. I found that fourteen states

charge a medical co-pay that is equivalent to charging minimum wage workers more than $200.

The excessive burden of medical fees and co-pays is most obvious in states where many or all incarcerated people are paid nothing for their work: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. Texas

is the most extreme example, with a flat $100 yearly health services fee, which some officials are actually trying to double to $200. People incarcerated in these states must rely on deposits into their personal accounts – typically from family – to pay medical fees. In most places, funds are automatically withdrawn from these accounts until the balance is paid, creating a debt that can follow them even after release.

Co-pays that take a large portion of prison wages make seeking medical attention a costly choice.

Co-pays in the hundreds of dollars would be unthinkable for non-incarcerated minimum wage earners. So why do states think it’s acceptable to charge people making pennies per hour such a large portion of their earnings? Some might argue that incarcerated people have nothing better to spend wages on than medical care. But wages allow incarcerated people to buy things they need that the prison does not provide: toiletries, over-the-counter medicine, additional clothes and shoes, as well as phone cards, stamps, and paper to help them maintain contact with loved ones. Co-pays that take a large portion of prison wages make seeking medical attention a costly choice.

Part of the justification for charging incarcerated people medical co-pays is to force them to make difficult choices. Administrators want to deter “frivolous” medical visits. The National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC), however, argues that abuses of sick call can be managed with “a good triage system,” without imposing fees that also deter necessary medical services. And although providers must treat people regardless of their ability to pay, incarcerated people with “low health literacy” may not understand this right. The NCCHC warns that co-pays may actually jeopardize the health of incarcerated populations, staff, and the public.

Out-of-reach co-pays in prisons and jails have two unintended but inevitable consequences which make them counterproductive and even dangerous. First, when sick people avoid the doctor, disease is more likely to spread to others in the facility – and into the community, when people are released before being treated. Second, illnesses are likely to worsen as long as people avoid the doctor, which means more aggressive (and expensive) treatment when they can no longer go without it. Correctional agencies may be willing to take that risk and hope that by the time people seek care, their treatment will be someone else’s problem. But medical co-pays encourage a dangerous waiting game for incarcerated people, correctional agencies, and the public – which none of us can afford.

For details and sourcing information on co-pays (and what happens when incarcerated patients can’t afford them), see the Appendix.

March 2020 update: Please see our post about legislative changes in California, Illinois, and Texas to see what has changed since we first published this briefing, and our page tracking correctional responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, which includes temporary suspensions of copays in some states.

This table includes co-pay fees for non-emergency, patient-initiated visits with medical staff. The co-pay average excludes Texas, which charges on a yearly basis rather than per-service. For details and sourcing information on co-pays, see the Appendix. For information on wages, see “How much do incarcerated people earn in each state?” State minimum wage information was obtained from the National Conference of State Legislatures. Exceptions: for states with no minimum wage law or minimum wages below the federal law, I used the federal minimum wage. For states with two tiers of minimum wages for free-world workers, I used the higher wages that apply to larger businesses (Minn., Mont., Ohio, and Okla.). For Nevada, I used the lower of the two minimum wage tiers, which applies to jobs with health benefits.

Footnotes (including updates)

This was updated April 28, 2017 with information from a new source on wages for Oklahoma’s regular prison jobs (non-industry). The source used when this was first posted did not state a minimum prison wage, only a maximum. According to DOC policy, however, the minimum wage for regular jobs is $7.23 per month, or about 5 cents per hour. A $4 co-pay for someone earning that much is the equivalent of a $580 co-pay charged to a non-incarcerated minimum wage earner in Oklahoma. The table, text, and graphs in this post have been updated to reflect Oklahoma’s updated information. ↩

As of 2019, the Texas legislature had made progress by replacing the notorious $100 fee Texas had charged incarcerated people with a $13.55 per-visit fee. While this change marks a substantial improvement, incarcerated people in Texas – who earn nothing for their labor – continue to be charged the highest medical co-pay in state prisons nationwide. ↩

In 2019, California passed legislation ending medical co-pays in prisons and jails. ↩

In 2019, Illinois passed legislation ending medical co-pays in state prisons and juvenile residential placement facilities. ↩

As of 2019, the Texas legislature had made progress by replacing the notorious $100 fee Texas had charged incarcerated people with a $13.55 per-visit fee. While this change marks a substantial improvement, incarcerated people in Texas – who earn nothing for their labor – continue to be charged the highest medical co-pay in state prisons nationwide. ↩

Wendy Sawyer is the Prison Policy Initiative Research Director. (Other articles | Full bio | Contact)

Related briefings:

Momentum is building to end medical co-pays in prisons and jails +

Food for thought: Prison food is a public health problem +

Phone Tag to Computer Hack: Securus puts privacy at risk +

Other posts by this author

|

2023 may 31

|

2023 mar 20

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

More... |

Replies