Transcription

5 things to know about our investigation into Mississippi's prison crisis

Alissa Zhu, Mississipi Clarion Ledger Published 12:03 p.m. CT March 4, 2020

Here are five takeaways from the Clarion Ledger's investigation into Mississipi's prison crisis.

Four factors contributed to the crisis, experts say

After an eruption of violence at Mississipi prisons, many were left wondering: How did we get here? Who is at fault?

According to inmates and experts interviewed by the Clarion Ledger, including a former corrections commissioner, a longtime prison monitor, and advocates for reform, factors include:

1. Sentencing policies leading to high rates of incarceration

2. Political appointments of corrections commissioners who had no experience running prisons

3. Funding cuts to the Mississippi Department of Corrections by Mississipi lawmakers

4. MDOC's lack of transparency

Read the story here: Mississipi prison's a ticking time bomb' How did we get here? Who's at fault? (https://www.clarionledger.com/in-depth/news/politics/2020/03/04/mississipi-prisons-rocked-deaths-riots-how-did-we-get-here/4659820002/)

More people were killed in prison in January than any other year in recent memory

In January alone, there were more prison homicides than the total for any other year since at least 2014. One longtime prison watchdog said the level of violence was unprecedented in recent memory.

Since Dec. 29, 22 people have died while in custody of MDOC.

Analysis: For inmates, Mississipi is a deadlier state than most. This year could be a record (https://www.clarionledger.com/in-depth/news/2020/03/04/inmates-mississipi-prisons-deadlier-than-most/2858516001/)

The founding of Mississipi's oldest and most infamous prison was rooted in brutality and racism

Historically known as Parchman Farm, the Mississipi State Penitentiary was established in 1901 and now occupies a sprawling 18,000 acres in the heart of the fertile Delta. It was, as Historian David Oshinsky said (https//glc.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/events/cbss/Oshinsky.pdf), "the closest thing to slavery that survived the Civil War."

Now some activists — including celebrities Jay-Z and Yo Gotti (https://twitter.com/AlissaZhu/status/1233114566797799426?s=20) — are calling on the state to shut down Parchman and end its "legacy of despair" (/story/news/2020/01/15/parchman-unit-29-found-unsafe-mississippi-prison-inmates/4465269002/) forever.

Learn more: Hard time, brutal conditions: A history of Parchman prison (https://www.clarionledger.com/in-depth/news/politics/2020/03/04/mississipi-

====

https://morethanourcrimes.medium.com/rehabilitation-or-retribution-79d0e0155cc9

Rehabilitation vs retribution

Which better serves justice?

Is justice served if incarcerated individuals’ time in prison doesn’t serve the purpose of rehabilitation?

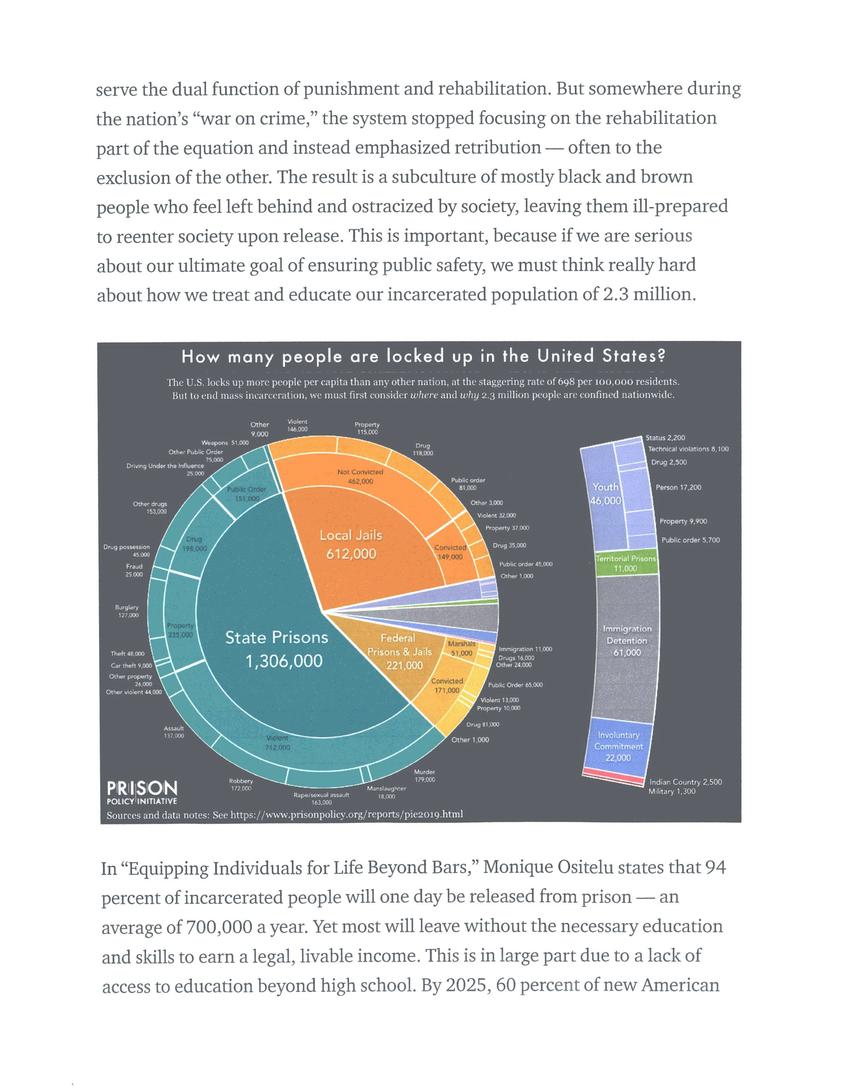

Marc Howard explains in his book, “Unusually Cruel: Prisons, Punishment and the Real American Exceptionalism, ”that prisons were originally established to serve the dual function of punishment and rehabilitation. But somewhere during the nation’s “war on crime,” the system stopped focusing on the rehabilitation part of the equation and instead emphasized retribution — often to the exclusion of the other. The result is a subculture of mostly black and brown people who feel left behind and ostracized by society, leaving them ill-prepared to reenter society upon release. This is important, because if we are serious about our ultimate goal of ensuring public safety, we must think really hard about how we treat and educate our incarcerated population of 2.3 million.

In “Equipping Individuals for Life Beyond Bars,” Monique Ositelu states that 94 percent of incarcerated people will one day be released from prison — an average of 700,000 a year. Yet most will leave without the necessary education and skills to earn a legal, livable income. This is in large part due to a lack of access to education beyond high school. By 2025, 60 percent of new American jobs will require some level of postsecondary education, yet it’s estimated that only 35% of state prisons and 24% of federal institutions provide college-level courses. (In fact, 41% of the incarcerated population don’t even have a high school diploma.)

The cost of so this failure in public policy is clear: A RAND Corp. report has shown that individuals who participate in any type of educational program while in prison are 43 percent less likely to return.

My own story is a testament to how a person who is locked up, punished and made to feel like an “inmate” turns out vs. an individual who is treated humanely and allowed the opportunity to develop and rehabilitate themselves:

I knew I was in a different world when I first walked into the receiving and discharge area of the D.C. jail and a correctional officer, whom I knew from back in the day, stuck out his hand to greet me. I looked at his hand like it was a snake until he got the message and pulled back. Coming from a culture (a federal penitentiary) where there is a clear line of division between and officers and the incarcerated, I “knew” that officers didn’t fraternize with inmates and inmates didn’t shake our adversary’s hand. The simple act of shaking a guard’s hand was grounds for my peers to ostracize or even kill me, and for the officer to be ridiculed by his coworkers for being an “inmate lover.” In the violent, volatile prison culture, inmates are daily reminded of their nothingness. And in turn, we internalize these feelings, creating an us vs. them mentality.

But that changed when I returned to the D.C. jail while my case was reviewed in local court. (D.C. does not have its own prison; instead, inmates are shipped across the country to federal institutions.) The cause for such a dramatic change was deceptively simple: the humanizing way in which I have been treated since I arrived and the college experience I now through Georgetown University’s Prison Scholars Program. This has reconfirmed my humanity and serves as a sort of “halfway house,” playing a huge role in my rehabilitation.

The other day, I watched College Beyond Bars, a video series by Lynn Novick film that illustrates the rehabilitative effects of higher education. I immediately identified with the humanizing stories the prisoners shared. The Georgetown Prison Scholars program has not only allowed me to become more educated, it also has helped me develop in ways that cannot be measured on a scholastic scale. A lot of times, I will be debating a particular topic with my “outside” classmates or professors and be forced to open my mind to different perspectives because I am not conversing with my highly limited peer group. That has really helped me reevaluate my past beliefs. In the film, the prisoners took ownership for staying out of trouble, because they now understood how their negative actions could stop them from attending college. Likewise, my Georgetown family invests so much love and care into me and my peers that I feel obligated to be successful in life. This is the power of real rehabilitation: It propels you to strive for greatness — and inspires belief that it is possible.

The prison warden in Novick’s series made this statement: “I would rather inmates study for a test and worry about how they are going to get a good grade, than to worry about how they can do mayhem or get drugs past my officers.” This is what all prison stakeholders should be thinking. Not only will these warden’s prisons be safer but also, society eventually gains a person who is prepared to be a productive citizen.

Of course, some prisoners can rehabilitate themselves without external aid, despite the abuse. And some who have access to quality programs resist change when success offers no hope — like for one friend who has been sentenced to life without parole. But these are the exceptions, not the rule.

So, why are we continuing to punish our prisoners, when rehabilitation serves both the prisoner and society so much better?

A note about how this blog is possible: Incarcerated people have no access to the internet. Thus, I am partnering with journalist/storyteller Pam Bailey, who acts as my editor when needed and posts all of my updates. You may contact her at paminprogress@gmail.com.

Other posts by this author

|

2023 may 31

|

2023 mar 20

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

2022 aug 23

|

More... |

Replies (2)